Eastern Approaches

It is divided into three parts: his life as a junior diplomat in Moscow and his travels in the Soviet Union, especially the forbidden zones of Central Asia; his exploits in the British Army and SAS in the North Africa theatre of war; and his time with Josip Broz Tito and the Partisans in Yugoslavia.

From Alma Ata Maclean took the train for Tashkent, passing through villages where "nothing seemed to have changed since the time when the country was ruled over by the Emir of Bokhara"; men still rode bulls and women still wore veils made of black horsehair.

When the weather became more conducive to travel, Maclean began his third and longest trip, aiming for Chinese Turkestan, immediately east of the Soviet Central Asian republics he had reached in 1937.

His fourth and final Soviet trip was once more to Central Asia, spurred by the desire to reach Bokhara (Bukhara, Uzbekistan), the capital of the emirate which had been closed to Europeans until recent times.

Maclean recounts how Charles Stoddart and Arthur Conolly were executed there in the context of The Great Game, and how Joseph Wolff, known as the Eccentric Missionary, barely escaped their fate when he came looking for them in 1845.

In early October 1938 Maclean set out again, first for Ashkhabad (Ashgabat, capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic), then through the Kara Kum (Black Desert), not breaking his journey at either Tashkent or Samarkand, but pushing on to Kagan, the nearest point on the railway to Bokhara.

After trying to smuggle himself aboard a lorry transporting cotton, he ended up walking to the city, and spent several days sight-seeing "in the steps of the Eccentric Missionary" and sleeping in parks, much to the frustration of the NKVD spies who were shadowing him.

After more negotiations, he managed to cross the river and thus leave the USSR, and from that point his only guide seems to have been the narrative of "the Russian Burnaby", a colonel Nikolai Ivanovich Grodekov, who rode from Samarkand to Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat in 1878.

After a night in Mazar, Maclean managed to get a car and driver, and progressed as rapidly as he could to Doaba, a village half-way to Kabul, where he had arranged to meet the British minister (i.e., ambassador), Colonel Frazer-Tytler.

He was invited to join the newly formed Special Air Service (SAS), where, as part of the Western Desert Campaign, he planned and executed raids on Axis-held Benghazi, on the coast of Libya (Operation Bigamy).

When it became clear that the North African Campaign was drawing to a close towards the end of 1942 and it became too quiet for his taste, he travelled east to arrest General Fazlollah Zahedi, at the time the head of the Persian armed forces in the south.

Maclean's convoy drove to the Gebel across the Sand Sea at its narrowest point, Zighen, and made it there undetected, although "bazaar gossip" from an Arab spy indicated that the enemy expected an imminent attack.

They were concerned about the influence of Fazlollah Zahedi, the general in charge of the Persian forces in the Isfahan area, who, their intelligence told them, was stockpiling grain, liaising with German agents, and preparing an uprising.

General Wilson was being transferred to Middle East Command, and Maclean extracted a promise that the newly trained troops would go with him, as their style of commando raids were ideal for southern and eastern Europe.

Frustrated by the abandoning of plans for an assault on Crete, Maclean went to see Reginald Leeper, "an old friend from Foreign Office days, and now His Majesty's Ambassador to the Greek Government then in exile in Cairo".

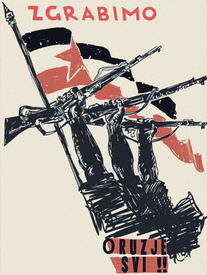

Churchill told him to parachute into Jugoslavia (now spelled Yugoslavia) as head of a military mission accredited to Josip Broz Tito (a shadowy figure at that point) or whoever was in charge of the Partisans, the Communist-led resistance movement.

In the late summer of 1943, Maclean parachuted into Bosnia with Vivian Street and Slim Farish (whom he called his British and American Chiefs of Staff, respectively) and Sergeant Duncan, his bodyguard.

Some of the characters close to Tito whom Maclean met in his first months in Bosnia were Vlatko Velebit, an urbane young man about town, who later went with Maclean to Allied HQ as a liaison officer; Father Vlado (Vlada Zečević), a Serbian Orthodox priest, "raconteur and trencherman"; Arso Jovanović, the Chief of Staff; Edo Kardelj, the Marxist theoretician who ended up vice-premier; Aleksandar Ranković, a professional revolutionary and Party organiser; Milovan Đilas (Dzilas), who became vice-president; Moša Pijade, one of the highest-ranking Jews; and a young woman named Olga whose father Momčilo Ninčić had been a minister in the Royalist government and who spoke English like a debutante.

Officers and soldiers under Maclean's command included Peter Moore of the Royal Engineers; Mike Parker, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster general; Gordon Alston; John Henniker-Major, a career diplomat; Donald Knight, and Robin Whetherly.

Maclean made contact with Bill Deakin, an Oxford history don who had served as a research assistant to Churchill; Anthony Hunter, a Scots Fusilier, and Major William Jones, an enthusiastic but unorthodox one-eyed Canadian.

Eventually, after an all-night march across noisy stony ground, dodging German patrols as they crossed a major road, the little group reached Zadvarje, where they were greeted with astonishment as creatures from another world "as indeed in a sense we were".

Maclean decided he needed to discuss matters with Tito and then with Allied superiors in Cairo to argue for more resources to push the project forward, and accordingly made his way back to Partisan HQ in Jajce.

Despite the tension over the anticipated invasion of Normandy, the press and officials were eager to hear the Yugoslav story, and Maclean and Velebit had a busy time; even U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower wanted to meet them.

Vis had been transformed in the intervening months, becoming a substantial base for aircraft, commandos, and navy boats "engaged in piratical activities against enemy shipping up and down the whole length of the Jugoslav coastline from Istria to Montenegro".

It was necessary to discuss the future shape of Yugoslavia at the highest possible level, and so Maclean was instructed to invite Tito and his entourage to Caserta, the Allied Force Headquarters near Naples.

Ralph Stevenson, the British Ambassador to this government in exile, accompanied Šubašić to Vis, but he and Maclean stayed out of the negotiations and spent their days swimming and speculating.

"Already the Fortresses were over their target -- were past it -- when, as we watched, the whole of Leskovac seemed to rise bodily into the air in a tornado of dust and smoke and debris, and a great rending noise fell on our ears.

They travelled for several days through prosperous countryside, "so surprising after Bosnia and Dalmatia", where the peasants, who expressed great friendship for Britain and a certain caution about the Partisans, gave them lavish hospitality and food.

When they reached the HQ of General Peko Dapčević, his chief of staff, who had only a vague notion of the geography of the city, took Maclean and Vivian Street out for a tour, through heavy shelling to which he appeared oblivious.

The bargaining went on for months, and meanwhile Maclean's staff wanted to get away, to assist guerrilla wars elsewhere When the Big Three (Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin) met at Yalta in February 1945 and made it clear that Tito and Šubašić had to get on with it, King Peter gave in, and all the pieces fell into place.