Western African Ebola epidemic

An additional cause for concern is the apparent ability of the virus to "hide" in a recovered survivor's body for an extended period and then become active months or years later, either in the same individual or in a sexual partner.

Extreme poverty, dysfunctional healthcare systems, distrust of government after years of armed conflict, and the delay in responding for several months, all contributed to the failure to control the epidemic.

[44][45] On 25 March 2014, the WHO indicated that Guinea's Ministry of Health had reported an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in four southeastern districts and that suspected cases in the neighbouring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone were being investigated.

[63] In February 2015, Guinea recorded a rise in cases; health authorities stated that this was related to the fact that they "were only now gaining access to faraway villages", where violence had previously prevented them from entering.

Guinean Red Cross teams said they had suffered an average of 10 attacks a month over the previous year;[65] MSF reported that acceptance of Ebola education remained low and that further violence against their workers might force them to leave.

[80] [81] On 19 March, it was also reported by the media that another individual had died due to the virus at the treatment centre in Nzerekore,[82] consequently, the country's government quarantined an area around the home where the cases took place.

[91] In September 2016, findings were published suggesting that the resurgence in Guinea was caused by an Ebola survivor who, after eight months of abstinence, had sexual relations with several partners, including the first victim in the new outbreak.

[95] On 11 June Sierra Leone shut its borders for trade with Guinea and Liberia and closed some schools in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus;[96] on 30 July the government began to deploy troops to enforce quarantines.

[125][126] On 26 January WHO Director-General, Dr Margaret Chan officially confirmed that the outbreak was not yet over;[28] that same day, it was also reported that Ebola restrictions had halted market activity in Kambia District amid protests.

[133] On 27 July, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf announced that Liberia would close its borders, with the exception of a few crossing points such as Roberts International Airport, where screening centres would be established.

[162][163] Health officials were concerned because the child had not recently travelled or been exposed to someone with Ebola and the WHO stated that "we believe that this is probably again, somehow, someone who has come in contact with a virus that had been persisting in an individual, who had suffered the disease months ago.

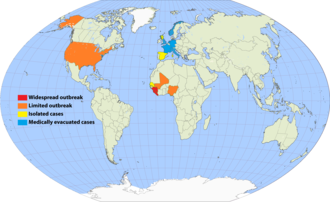

[216][217] A fourth case was identified on 23 October 2014, when Craig Spencer, an American physician who had returned to the United States after treating Ebola patients in Western Africa, tested positive for the virus.

[44] However, further studies have shown that the outbreak was likely caused by an Ebola virus lineage that spread from Middle Africa via an animal host within the last decade, with the first viral transfer to humans in Guinea.

[261] In August 2014, the WHO published a road map of the steps required to bring the epidemic under control and to prevent further transmission of the disease within Western Africa; the coordinated international response worked towards realising this plan.

[63] Furthermore, most past epidemics had occurred in remote regions, but this outbreak spread to large urban areas, which had increased the number of contacts an infected person might have and made transmission harder to track and break.

According to the director of the NGO Plan International in Guinea, "The poor living conditions and lack of water and sanitation in most districts of Conakry pose a serious risk that the epidemic escalates into a crisis.

[284] Speaking on 27 January 2015, Guinea's Grand Imam, the country's highest cleric, gave a very strong message saying, "There is nothing in the Koran that says you must wash, kiss or hold your dead loved ones," and he called on citizens to do more to stop the virus by practising safer burying rituals that do not compromise tradition.

On 8 August 2014, a cordon sanitaire, a disease-fighting practice that forcibly isolates affected regions, was established in the triangular area where Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone are separated only by porous borders and where 70 percent of the known cases had been found.

Speaking from a remote region, an MSF worker said that a shortage of protective equipment was making the medical management of the disease difficult and that they had limited capacity to safely bury bodies.

[338] Speaking on 12 September, WHO Director-General, Margaret Chan, said: "In the three hardest hit countries, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, the number of new cases is moving far faster than the capacity to manage them in the Ebola-specific treatment centres.

[348][349] UNICEF, USAID and Samaritan's Purse began to take measures to provide support for families that were forced to care for patients at home by supplying caregiver kits intended for interim home-based interventions.

[378] The three most affected countries—Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone—are among the poorest in the world, with extremely low levels of literacy, few hospitals or doctors, low-quality physical infrastructure, and weakly functioning government institutions.

[390][391] On 9 September, Jonas Schmidt-Chanasit of the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Germany, controversially announced that the containment fight in Sierra Leone and Liberia had already been "lost" and that the disease would "burn itself out".

[12] They further stated, that if the disease was not adequately contained it could become native in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, "spreading as routinely as malaria or the flu",[393] and according to an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, eventually to other parts of Africa and beyond.

[400] Despite the end of civil violence in 2003 and inflows from international donors, the reconstruction of Liberia had been very slow and non-productive—water delivery systems, sanitation facilities, and centralised electricity were practically non-existent, even in Monrovia.

Speaking at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Liberian president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf said the amount was needed because "[o]ur health systems collapsed, investors left our countries, revenues declined and spending increased.

[438] On 25 January, the IMF projected a GDP growth of 0.3% for Liberia, that country indicating it would cut spending by 11 per cent due to a stagnation in the mining sector, which would cause a domestic revenues drop of $57 million.

[449]: 245 In May 2015, Dr. Margaret Chan indicated, "demands on WHO was more than ten times greater than ever experienced in the almost 70-year history of this Organization"[450][451] and on 23 March, she stated that "the world remains woefully ill-prepared to respond to outbreaks that are both severe and sustained.

Speaking on 3 September, the International President of MSF spoke out concerning the lack of assistance from United Nations (UN) member countries: "Six months into the worst Ebola epidemic in history, the world is losing the battle to contain it.

"[456] In April 2015, the WHO admitted very serious failings in handling the crisis and indicated reforms for any future crises; "we did not work effectively in coordination with other partners, there were shortcomings in risk communications and there was confusion of roles and responsibilities".