Echo parakeet

The echo parakeet was also hunted by early visitors to Mauritius and due to destruction and alteration of its native habitat, its numbers declined throughout the 20th century, reaching as few as eight to 12 in the 1980s, when it was referred to as "the world's rarest parrot".

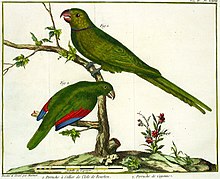

In 1783, the Dutch naturalist Pieter Boddaert coined the scientific name Psittacus eques, based on a plate by the French artist François-Nicolas Martinet, which accompanied Buffon's account of the Réunion bird in his work Histoire Naturelle.

[6] In 1876, the British ornithologists and brothers Alfred and Edward Newton pointed out that the avifauna of Réunion and Mauritius were generally distinct from each other, and that this might, therefore, also be true of the parakeets.

In 1907, British zoologist Walter Rothschild supported the separation of the two species on account of the other birds of Réunion and Mauritius being distinct, while noting that how they differed was unknown.

The specimen's original label referred specifically to Levaillant's plate of the "perruche a double collier", illustrated by the French artist Jacques Barraband, which was meant to depict the parakeet of Réunion.

He noted that the skeletal anatomy of the echo parakeet was mainly known from fossil bones, as it was the Mauritian parrot most commonly found in cave deposits, and that skeletons are rare in museum collections.

Hume suggested they shared a common origin within the Psittaculini radiation, based on morphological features and the fact that Psittacula parrots have managed to colonise many isolated islands in the Indian Ocean.

[4] In 2008, Cheke and Hume suggested that this group may have invaded the area several times, as many of the species were so specialised that they may have diverged on hot spot islands before the Mascarenes emerged from the sea.

They suggested that since some of the Indian Ocean island species had diverged early within their clades, including the echo parakeet within P. krameri, Africa and Asia may have been colonised from there rather than the other way around.

They also called attention to a usually overlooked, unlabelled sketch from around 1770 by French artist Paul Philippe Sanguin de Jossigny of a ring-necked parakeet with a collar encircling the neck, which they thought could have been from either island.

[23] The following year, Jones and colleagues, including authors of the DNA studies, Hume, and Forshaw, supported the identification of the Edinburgh specimen as a Réunion parakeet and the subspecific differentiation between the populations.

Since populations on islands usually have lower genetic diversity than those on continents, they stated that the low level of differentiation between the Mauritius and Réunion specimens would be expected.

[12] In 2020, Jansen and Cheke pointed out that Marinet's plate that serves as the type illustration of P. eques differs considerably in colouration between copies (some have yellow on the upper breast while others do not, for example).

They concluded that these were hand-coloured by different people after an unidentified master plate by Martinet, but since it cannot be established which of the copies that accurately represents the specimen they depicted, Jansen and Cheke found it safer to rely on the description by Brisson.

They also found that there was no evidence to reliably confirm what island the Edinburgh skin was collected from, and that since it was unknown to the French encyclopaedists that echo parakeets also lived on Mauritius, birds matching their descriptions were assigned to Réunion by default.

They suggested that Psittaculinae originated in the Australo–Pacific region (then part of the supercontinent Gondwana), and that the ancestral population of the Psittacula–Mascarinus lineage were the first psittaculines in Africa by the late Miocene (8–5 million years ago), and colonised the Mascarenes from there.

They usually roost in sheltered areas on hillsides and ravines, preferring trees with dense foliage (such as Eugenia, Erythroxylum, or Labourdonnaisia), where they perch close to the trunks or in cavities.

[11] As in their relatives, the neck and head patterns of the echo parakeet are displayed during courtship and are therefore sexually selected, with variation and intensity of the colours probably signifying fitness.

The birds nest in natural cavities, often in large, old native trees, such as Calophyllum, Canarium, Mimusops, and Sideroxylon, at least 10 m (33 ft) above the ground, and not exposed to the south east, which is affected by trade winds.

The tracts are more visible after ten days when down tips breakthrough, their eyes are slit-like as they begin to open, and the legs turn from pinkish to pale grey.

The eyes are almost fully open after fifteen days, and the chicks have a fine covering of greenish-grey down on most of the body, the secondary quills emerge, and feather tracts appear on the crown of the head.

[31] A preliminary 2009 genetic study by Taylor and Parkin showed that matings of "auxiliary males" with the female of a breeding pair do occur, and that the echo parakeet is therefore not strictly monogamous.

Parakeets must have had an impact on seed production of favoured plants in the past; some fruits have a very hard epicarp (the tough outer skin) resistant to parrots, which may have evolved for protection.

Some species have a hard epicarp surrounded by a fleshy pericarp which is eaten by echo parakeets, after which they reject the former, which probably contributes to seed dispersal.

[11] They compete for food with the monkeys, and their diet overlaps with that of the pink pigeon (Nesoenas mayeri), the Mauritius bulbul (Hypsipetes olivaceus), and the Mauritian flying fox (Pteropus niger).

Areas where the echo parakeet could be found were cleared for tea and forestry from the 1950s to the 1970s, and the birds were forced into the remaining native habitat, in and around the Black River Gorges.

Since the carrying capacity of the Black River Gorges National Park had reached its limit, echo parakeets were released in the mountains of eastern Mauritius around 2016, and it has been suggested that birds could be introduced to the other Mascarene Islands.

Since it has been suggested that some endemic trees and parrots on the Mascarenes co-evolved, reintroducing the echo parakeet could aid in seed-dispersal, a function previously carried out by its extinct relatives.

[41] The main threat to the species is destruction and alteration of its native habitat, resulting in the loss of feeding areas, which would force the birds to travel widely to find food.

Rats and crab-eating macaques prey on parakeet eggs and chicks (even nesting parents have been killed by the latter), and the monkeys are also the most serious competitors for food since they strip fruits off trees before they are ripe.