Ecological sanitation

[1] It is an approach, rather than a technology or a device which is characterized by a desire to "close the loop", mainly for the nutrients and organic matter between sanitation and agriculture in a safe manner.

Thus, the recycled human excreta product, in solid or liquid form, shall be of high quality both concerning pathogens and all kind of hazardous chemical components.

[1] The first proponents of ecosan systems had a strong focus on increasing agricultural productivity (via the reuse of excreta as fertilizers) and thus improving the nutritional status of the people at the same time as providing them with safe sanitation.

Reuse trials in Zimbabwe showed positive results for using urine on green, leafy plants such as spinach or maize as well as fruit trees.

[9] Urine has been proven in many studies to be a valuable, relatively easy to handle fertilizer, containing nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and important micro-nutrients.

[citation needed] Some proponents of ecosan have been criticized as being too dogmatic, with an over-emphasis on environmental resource protection rather than a focus on public health protection and provision of sanitation at a very low cost (for example UDDTs, which some people call "ecosan toilets", may be more expensive to build than pit latrines, even if in the longer term they are cheaper to maintain).

Acknowledgement for ecosan came with the awarding of the Stockholm Water Prize in 2013 to Peter Morgan, a pioneer of handpumps and ventilated pit latrines (VIPs) in addition to ecosan-type toilets[7][15] (the Arborloo, the Skyloo[16] and the Fossa alterna).

Peter Morgan is renowned as one of the leading creators and proponents of ecological sanitation solutions, which enable the safe reuse of human excreta to enhance soil quality and crop production.

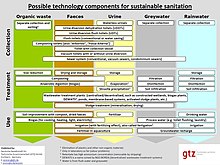

Ecosan offers a flexible framework, where centralized elements can be combined with decentralized ones, waterborne with dry sanitation, high-tech with low-tech, etc.

[19][20] The recovery and use of urine and feces in "dry sanitation systems", i.e. without sewers or without mixing substantial amounts of water with the excreta, has been practiced by almost all cultures.

[21] Many traditional agricultural societies recognized the value of human waste for soil fertility and practised the "dry" collection and reuse of excreta.

[22] The value of "night soil" as a fertilizer was recognized with well-developed systems in place to enable the collection of excreta from cities and its transportation to fields.

The Chinese were aware of the benefits of using excreta in crop production more than 2500 years ago, enabling them to sustain more people at a higher density than any other system of agriculture.

[21] This practice was also called gong farmer in England but carried many health risks for those involved with transporting the excreta and fecal sludge.

[26] Traditional forms of sanitation and excreta reuse have continued in various parts of the world for centuries and were still common practice at the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

Even as the world became increasingly more urbanised, the nutrients in excreta collected from urban sanitation systems without mixing with water were still used in many societies as a resource to maintain soil fertility, despite rising population densities.

[27][28] A publication by Sida called "Ecological sanitation" in 1998 compiled the knowledge generated to date about ecosan in a popular book which was published as a second edition in 2004.

In fact, the Sustainable Sanitation Alliance was founded in 2007 in an attempt to broaden the ecosan concept and to bring together various actors under one umbrella.

Research into how to make reuse of urine and feces safe in agriculture was carried out by Swedish researchers, for example Hakan Jönsson and his team, whose publication on "Guidelines on the Use of Urine and feces in Crop Production"[33] was a milestone which was later incorporated into the WHO "Guidelines on Safe Reuse of Wastewater, Excreta and Greywater" from 2006.