Economic history

It emphasizes historicizing the economy itself, analyzing it as a dynamic entity and attempting to provide insights into the way it is structured and conceived.

They often focus on the institutional dynamics of systems of production, labor, and capital, as well as the economy's impact on society, culture, and language.

Economics teaches us to look out for the right facts in reading history and makes matters such as introducing enclosures, machinery, or new currencies more intelligible.

"[3] In late-nineteenth-century Germany, scholars at a number of universities, led by Gustav von Schmoller, developed the historical school of economic history.

The approach was spread to Great Britain by William Ashley (University of Oxford) and dominated British economic history for much of the 20th century.

The term was originally coined by Jonathan R. T. Hughes and Stanley Reiter and refers to Clio, who was the muse of history and heroic poetry in Greek mythology.

[9] Cliometricians argue their approach is necessary because the application of theory is crucial in writing solid economic history, while historians generally oppose this view warning against the risk of generating anachronisms.

However, counterfactualism was not its distinctive feature; it combined neoclassical economics with quantitative methods in order to explain human choices based on constraints.

Despite the pessimistic view on the state of the discipline espoused by many of its practitioners, economic history remains an active field of social scientific inquiry.

Some less developed countries, however, are not sufficiently integrated in the world economic history community, among others, Senegal, Brazil and Vietnam.

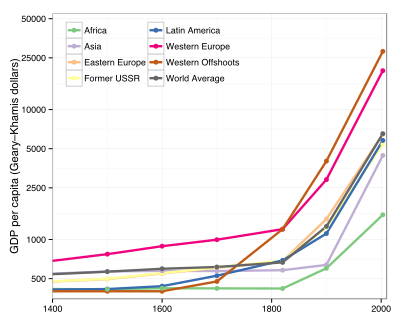

[19] Studying economic growth has been popular for years among economists and historians who have sought to understand why some economies have grown faster than others.

A more recent work is Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson's Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012) which pioneered a new field of persistence studies, emphasizing the path-dependent stages of growth.

[20] Other notable books on the topic include Kenneth Pomeranz's The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (2000) and David S. Landes's The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some are So Rich and Some So Poor (1998).

Scholars have tended to move away from narrowly quantitative studies toward institutional, social, and cultural history affecting the evolution of economies.

[22][23] Columbia University economist Charles Calomiris argued that this new field showed 'how historical (path-dependent) processes governed changes in institutions and markets.

'[24] However, this trend has been criticized, most forcefully by Francesco Boldizzoni, as a form of economic imperialism "extending the neoclassical explanatory model to the realm of social relations.

"[25] Conversely, economists in other specializations have started to write a new kind of economic history which makes use of historical data to understand the present day.

The book was well received by some of the world's major economists, including Paul Krugman, Robert Solow, and Ben Bernanke.

(2017), Pocket Piketty by Jesper Roine (2017), and Anti-Piketty: Capital for the 21st Century, by Jean-Philippe Delsol, Nicolas Lecaussin, Emmanuel Martin (2017).

One economist argued that Piketty's book was "Nobel-Prize worthy" and noted that it had changed the global discussion on how economic historians study inequality.

[33] In turn, in what was later coined the Brenner debate, Paul Sweezy, a Marxian economist, challenged Dobb's definition of feudalism and its focus only on western Europe.

It includes many topics traditionally associated with the field of economic history, such as insurance, banking and regulation, the political dimension of business, and the impact of capitalism on the middle classes, the poor and women and minorities.

[39] As a result, a new academic journal, Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics, was founded at the University of Pennsylvania under the direction of Marc Flandreau (University of Pennsylvania), Julia Ott (The New School, New York) and Francesca Trivellato (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) to widen the scope of the field.

The journal's goal is to bring together "historians and social scientists interested in the material and intellectual aspects of modern economic life.