Edward Kienholz

Art critic Brian Sewell called Edward Kienholz "the least known, most neglected and forgotten American artist of Jack Kerouac's Beat Generation of the 1950s, a contemporary of the writers Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and Norman Mailer, his visual imagery at least as grim, gritty, sordid and depressing as their literary vocabulary".

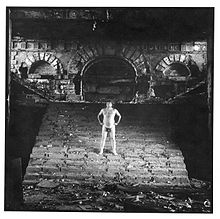

Despite his lack of formal artistic training, Kienholz began to employ his mechanical and carpentry skills in making collage paintings and reliefs assembled from materials salvaged from the alleys and sidewalks of the city.

[8] In 1958 he sold his share of the Ferus Gallery to buy a Los Angeles house and studio and to concentrate on his art, creating free-standing, large-scale environmental tableaux.

Set in the year 1943, Roxy's depicts Kienholz's memories of his youthful encounters in a Nevada brothel complete with antique furniture, a 30s era jukebox, vintage sundries, and satirical characters assembled from castoff pieces of junk.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors called it "revolting, pornographic and blasphemous",[6] and threatened to withhold financing for the museum unless the tableau was removed from view.

He would sell these works of early Conceptual Art (though the term was not in widespread use at the time) for a modest sum, giving the buyer the right (upon payment of a larger fee) to have Kienholz actually construct the artwork.

Live animals were selectively included as crucial elements in some installations, providing motion and sound that contrasted starkly with frozen tableaus of decay and degradation.

The bird is considered an integral part of the installation, but requires special attention to ensure that it remains healthy and active, as described in the Whitney Museum's online catalog and video.

[17] Kienholz's work commented savagely on racism, aging, mental illness, sexual stereotypes, poverty, greed, corruption, imperialism, patriotism, religion, alienation, and most of all, moral hypocrisy.

In 1977 he opened "The Faith and Charity in Hope Gallery" at their Idaho studio, and showed both established and emerging artists, including Francis Bacon, Jasper Johns, Peter Shelton, and Robert Helm.

Retrospectives of Kienholz's work have been infrequent, due to the difficulty and expense of assembling fragile, literally room-sized sculptures and installations from widely dispersed collections around the world.

[23] The diverse and freely improvised materials and methods used in Kienholz works pose an unusual challenge to art conservators who try to preserve the artist's original intent and appearances.

[24] In 2009, the National Gallery in London mounted an exhibition of The Hoerengracht (Dutch: Whores' Canal), a 1980s streetscape installation portraying the red light district of Amsterdam, Netherlands.

[9][25] In 2011, Kienholz's work was visited with renewed attention in Los Angeles partly as a result of the Pacific Standard Time series of exhibitions,[26] which saw his powerful 1972 installation Five Car Stud reinstalled at LACMA.

[4] In spite of his claims to be merely a rough working-class carpenter and mechanic, Kienholz was well aware of his position in the contemporary art scene, and acted assertively to shape his image and legacy.

[4] French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard's book Pacific Wall (Le mur du pacifique) is an extended meditation on Keinholz's Five Card Stud installation.