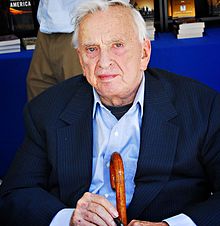

Gore Vidal

As a political commentator and essayist, Vidal's primary focus was the history and society of the United States, especially how a militaristic foreign policy reduced the country to a decadent empire.

[3] His third novel, The City and the Pillar (1948), offended the literary, political, and moral sensibilities of conservative book reviewers, the plot being about a dispassionately presented male homosexual relationship.

The baptismal ceremony was effected so he "could be confirmed [into the Episcopal faith]" at the Washington Cathedral, in February 1939, as "Eugene Luther Gore Vidal".

[12][13] At the U.S. Military Academy, the exceptionally athletic Vidal Sr. had been a quarterback, coach, and captain of the football team; and an all-American basketball player.

[16] Vidal's mother, Nina Gore, was a socialite who made her Broadway theater debut as an extra actress in Sign of the Leopard, in 1928.

[28] The cultural critic Harold Bloom has written that Vidal believed that his sexuality had denied him full recognition from the literary community in the United States.

Bloom himself contends that such limited recognition resulted more from Vidal's "best fictions" being "distinguished historical novels", a subgenre "no longer available for canonization".

[29] Vidal's literary career began with the success of the military novel Williwaw, a men-at-war story derived from his Alaskan Harbor Detachment duty during the Second World War.

[40] The New York Times, quoting critic Harold Bloom about those historical novels, said that "Vidal's imagination of American politics is so powerful as to compel awe.

[42] Even the occasionally hostile literary critic, such as Martin Amis, admitted that "Essays are what he is good at ... [Vidal] is learned, funny, and exceptionally clear-sighted.

In 2009, Vidal won the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation, which called him a "prominent social critic on politics, history, literature and culture".

In exchange for rewriting the Ben-Hur screenplay, on location in Italy, Vidal negotiated the early termination (at the two-year mark) of his four-year contract with MGM.

He also appeared in the American television series Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman and in the films Bob Roberts (1992), a serio-comedy about a reactionary populist politician who manipulates youth culture to win votes; With Honors (1994), an Ivy league comedy-drama; Gattaca (1997), a science-fiction drama about genetic engineering; and Igby Goes Down (2002), a coming-of-age serio-comedy directed by his nephew, Burr Steers.

[59] As a public intellectual, Vidal criticized what he viewed as political harm to the nation and the voiding of the citizen's rights through the passage of the USA Patriot Act (2001) during the George W. Bush administration (2001–2009).

The newspaper emphasized that Vidal, described as "the Grand Old Man of American belles-lettres", claimed that America is rotting away – and to not expect Barack Obama to save the country and the nation from imperial decay.

[72]In 1975, Vidal sued Truman Capote for slander, over the accusation that he had once been thrown out of the White House for being drunk, putting his arm around First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, and then insulting her mother.

In 1968, the ABC television network hired the liberal Vidal and the conservative William F. Buckley Jr. as political analysts of the presidential-nomination conventions of the Republican and Democratic parties.

[83] Buckley accepted a money settlement of $115,000 to pay the fee of his attorney and an editorial apology from Esquire, in which the publisher and the editors said that they were "utterly convinced" of the untruthfulness of Vidal's assertions.

Vidal responded:[88] I thought hell is bound to be a livelier place, as he joins, forever, those whom he served in life, applauding their prejudices and fanning their hatred.

On December 15, 1971, during the recording of The Dick Cavett Show, with Janet Flanner, Norman Mailer allegedly head-butted Vidal when they were backstage.

Asked his opinion about the arrest of the film director Roman Polanski, in Switzerland, in September 2009, in response to an extradition request by U.S. authorities, for having fled the U.S. in 1978 to avoid jail for the statutory rape of a thirteen-year-old girl in Hollywood, Vidal said: "I really don't give a fuck.

Asked for elaboration, Vidal explained the cultural temper of the U.S. and of the Hollywood movie business in the 1970s:[92] The [news] media can't get anything straight.

The idea that this girl was in her communion dress, a little angel, all in white, being raped by this awful Jew Polacko—that's what people were calling him—well, the story is totally different now [2009] from what it was then [1970s] ... Anti-Semitism got poor Polanski.

[93] In 1997, Vidal was one of thirty-four public intellectuals and celebrities who joined a publicity campaign waged by Scientologists against the German government, signing an open letter addressed to German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, published in the International Herald Tribune, alleging that Scientologists in Germany were treated "in the same way that the Nazi regime persecuted the Jews".

[94] Scientologists are free to operate in Germany; the Church of Scientology, however, is not recognized as a religious body but as a business with political goals and thus monitored by the German domestic intelligence service.

But regardless of tribal taboos, homosexuality is a constant fact of the human condition and it is not a sickness, not a sin, not a crime ... despite the best efforts of our puritan tribe to make it all three.

[100] Vidal would cruise the streets and bars of New York City and other locales and wrote in his memoir that by age twenty-five, he had had more than a thousand sexual encounters.

"[105] In Celebrity: The Advocate Interviews (1995), by Judy Wiedner, Vidal said that he refused to call himself "gay" because he was not an adjective, adding that, "to be categorized is, simply, to be enslaved.

[120] The Guardian said that "Vidal's critics disparaged his tendency to formulate an aphorism, rather than to argue, finding in his work an underlying note of contempt for those who did not agree with him.

The writer and comedian Dick Cavett was host of the Vidalian celebration, which featured personal reminiscences about and performances of excerpts from the works of Vidal by friends and colleagues, such as Elizabeth Ashley, Candice Bergen, Hillary Clinton, Alan Cumming, James Earl Jones, Elaine May, Michael Moore, Susan Sarandon, Cybill Shepherd, and Liz Smith.