Edmund the Martyr

He is thought to have been of East Anglian origin, but 12th century writers produced fictitious accounts of his family, succession and his rule as king.

Edmund's death was mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which relates that he was killed in 869 after the Great Heathen Army advanced into East Anglia.

Medieval versions of Edmund's life and martyrdom differ as to whether he died in battle fighting the Great Heathen Army, or if he met his death after being captured and then refusing the Viking leaders' demand that he renounce Christ.

A series of coins commemorating him was minted from around the time East Anglia was absorbed by the kingdom of Wessex in 918, and in about 986, the French monk Abbo wrote of his life and martyrdom.

[2] Medieval manuscripts and works of art relating to Edmund include Abbo's Passio Sancti Eadmundi, John Lydgate's 15th-century Life, the Wilton Diptych, and a number of church wall paintings.

[12] The army attacked Mercia by the end of 867 and made peaceful terms with the Mercians; a year later the Vikings returned to East Anglia.

[25] The St Edmund memorial coins were minted in great quantities by a group of more than 70 moneyers, many of whom appear to have originated from continental Europe; over 1800 specimens were found when the Cuerdale Hoard was discovered in Lancashire in 1840.

[20] The Danish king Canute, who ruled England from 1016,[29] converted to Christianity and was instrumental in founding the abbey at Bury St Edmunds.

[30] The new stone abbey church was completed in 1032, having possibly been commissioned by Canute in time to be consecrated on the 16th anniversary of the Battle of Assandun, which took place on 18 October 1016.

[32][note 3] After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, the abbot planned out over 300 new houses within a grid-iron pattern at a location that was close to the abbey precincts, a development which caused the town to more than double in size.

[34][35] King John is said to have given a great sapphire and a precious stone set in gold to the shrine, which he was permitted to keep upon the condition that it was returned to the abbey when he died.

[37] In 1664, a lawyer from the French city of Toulouse publicized a claim that Edmund's remains had been taken from Bury by the future Louis VIII of France following his defeat at the Battle of Lincoln in 1217.

Although their validity had been confirmed in 1874, when two pieces were given to Edward Manning, Archbishop of Westminster, concerns were raised about the authenticity of the Arundel relics by Montague James and Charles Biggs in The Times.

The relics remained at Arundel under the care of the Duke of Norfolk while a historical commission was set up by Cardinal Vaughan and Archbishop Germain of Saint-Sernin.

[53] According to Abbo, St Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury, was the source of the story of the martyrdom, which he had heard told long before, in the presence of Æthelstan, by an old man who swore an oath that he had been Edmund's sword-bearer.

Ridyard notes that the story that Edmund had an armour-bearer implies that he would have been a warrior king who was prepared to fight the Vikings on the battlefield, but she acknowledges the possibility that such later accounts belong to "the realm of hagiographical fantasy".

When Ivar the impious pirate saw that the noble king would not forsake Christ, but with resolute faith called after Him, he ordered Edmund beheaded, and the heathens did so.

Abbo named one of Edmund's killers as Hinguar, who can probably be identified with Ivarr inn beinlausi (Ivar the Boneless), son of Ragnar Lodbrok.

His death bears some resemblance to the fate suffered by other saints: St Denis was whipped and beheaded and the body of Mary of Egypt was said to have been guarded by a lion.

His original text does not survive, but a shortened version is part of a book dating to around 1100 produced by Bury St Edmunds Abbey, which is composed of Abbo's hagiography, followed by Herman's.

[65] De Infantia Sancti Edmundi, a fictitious 12th-century hagiography of Edmund's early life by the English canon Geoffrey of Wells, represented him as the youngest son of 'Alcmund', a Saxon king of Germanic descent.

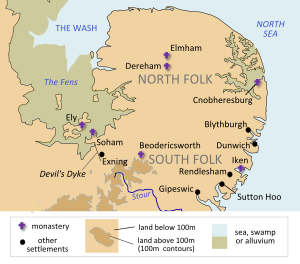

[67] Lydgate spoke of his parentage, his birth at Nuremberg, his adoption by Offa of Mercia, his nomination as successor to the king and his landing at Old Hunstanton on the North Norfolk coast to claim his kingdom.

[68] Biographical details of Edmund in the Catholic Encyclopedia, published in 1913, include that "he showed himself a model ruler from the first, anxious to treat all with equal justice, and closing his ears to flatterers and untrustworthy informers".

[77] Edmund is the patron saint of pandemics as well as kings,[78] the Roman Catholic diocese of East Anglia,[79] and Douai Abbey.

Of these saints, Edmund was the most consistently popular with English kings,[82] although Edward III raised the importance of George when he associated him with the Order of the Garter.

An illustrated copy of Abbo of Fleury's Passio Sancti Eadmundi, made at Bury St Edmunds in around 1130, is now kept at the Morgan Library in New York City.

Painted on oak panels, it shows Edmund and Edward the Confessor as the royal patrons of England presenting Richard to the Virgin and Child.

In the climactic scene of the poem, Edyff, the sister of King 'Athelston' of England, gives birth to Edmund after passing through a ritual ordeal by fire.