Eduard Roschmann

As a result of a fictionalized portrayal in the novel The Odessa File by Frederick Forsyth and its subsequent film adaptation, Roschmann came to be known as the "Butcher of Riga".

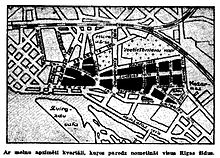

Furthermore, while it is common to see the Riga ghetto referred to as a single location, in fact it was a unified prison for only a very short time in autumn of 1941.

These people were tricked into believing they would be transported to a new and better camp facility at an area near Riga called Dünamünde.

In fact no such facility existed, and the intent was to transport the victims to mass graves in the woods north of Riga and shoot them.

[10][11] According to a survivor, Edith Wolff, Roschmann was one of a group of SS men who selected the persons for "transport" to Dünamünde.

Historians Angrick and Klein state that in addition to the mass killings, the Holocaust in Latvia also consisted of a great number of individual murders.

[17] ... the reading provided by witness accounts ... makes it clear that the genocide in occupied Riga consisted of an enormous number of individual murders in addition to the large-scale operations.

The image of the Holocaust in Latvia conveyed in these reports is not that of a gigantic impersonal killing machine, even if the plans for shooting the Jews of Riga in winter 1941 conjure up a process of mass murder based on division of labour.

[5] Survivor Nina Ungar related a similar incident at the Olaine peat bog work camp, where Roschmann found three eggs on one of the Latvian Jews and had him shot immediately.

[14] Kaufmann describes an incident, possibly the same one referred to by Ungar, where Roschmann, during a visit to the Olaine work camp with Gymnich in 1943, found a singer named Karp with five eggs and had him shot immediately.

[22] This was considered a favourable work assignment for Jews, as it involved skilled labour (vehicle mechanics) necessary for the German army, thus providing some protection from liquidation, and it also gave a number of opportunities to "organise" (that is, to buy, barter for or steal) contraband food and other items.

Roschmann heard rumours about the "good life",[23] and attempted to prevent it by putting some of the workers into one of the prisons or transferring them to Kaiserwald concentration camp.

[24] Roschmann was later transferred to the Lenta work camp, a forced-labour facility in the Riga area where Jews were housed at the workplace.

The original German commandant, Fritz Scherwitz, had determined to make a lot of money involving the work of highly skilled Jews in the tailoring trade.

[22]Roschmann participated in the efforts of Sonderkommando 1005 to conceal the evidence of the Nazi crimes in Latvia by exhuming and burning the bodies of the victims of the numerous mass shootings in the Riga area.

[4] In the fall of 1943, Roschmann was made the chief of Kommando Stützpunkt, a work detail of prisoners which was given the task of digging up and burning the bodies of the tens of thousands of people whom the Nazis had shot and buried in the forests of Latvia.

[28] As his source, Ezergailis cites a witness, Franz Leopold Schlesinger, who testified in the trial in West Germany of Viktors Arajs in the late 1970s, almost 35 years later.

Once again I was rescued from the firing squad, this time by my father's quick thinking.According to Gertrude Schneider, a historian and a survivor of the Riga ghetto, Roschmann was clearly a murderer, but was not uniformly cruel.

She records an instance where Krause, Roschmann's predecessor as commandant, had executed Johann Weiss, a lawyer from Vienna, and a First World War veteran, for having hidden money in his glove.

A year later, when Roschmann was commandant, his widow and daughter requested of him that he allow them the Jewish custom of visiting the grave.

Roschmann ... probably preened himself in front of his SS cronies when citing The Odessa File as proof of his ruthless efficiency three decades earlier.

Historian Bernard Press, a Latvian Jew who was able to hide outside of Riga and avoid confinement in the ghetto, describes Krause, Gymnich and Roschmann as having engaged in random shootings of human beings.

Roschmann had her confined in the Central Prison, where she was not in fact executed but released based on the recommendation of Krause, who had previously wanted the woman to become his mistress.

After visiting his wife in Graz, he was recognised with the assistance of former concentration camp inmates and arrested by the British military police.

Roschmann succeeded in escaping from this custody; in the process while running in hiding from a British patrol at the Austrian Border he was shot through the lung and also lost two toes of one foot to frostbite.

[45] In addition, the prominent Argentine journalist, Jacobo Timmerman, a Jew, had been arrested at that time and held incommunicado under circumstances which raised concern that he had been "subjected to ill-treatment" while in custody.

[3] The U.S. Embassy in Argentina sent a cable to the State Department which reported the situation and contained the following comment: The public and undiplomatic handling of the Argentine announcement concerning Roschmann raised speculation that it was a political move designed to placate the West Germans of human rights complaints and throw off charges of anti-Semitic attitudes within the government.

... [T]he timing of the announcement on the extradition case appears to be an effort to appease an irate West German government.

Simon Wiesenthal, however, was sceptical of the identification, claiming that a man matching Roschmann's description had been spotted in Bolivia only one month earlier.

[46] On the other hand, a report made five days after his death stated that the international police agency Interpol had confirmed the fingerprints on the body as matching prints of Roschmann on file at Argentina's police agency in Buenos Aires, and Wiesenthal said at that time that although he at first had doubted Paraguayan reports, he was "75 percent sure" that the body was that of Roschmann.