Edward Adamson

Subsequently, he trained and qualified as a chiropodist, at his parents' behest as they wanted him to have 'a proper profession', concerned about his livelihood as an artist.

Then Adamson returned to a career in art, working as a graphic artist at a Fleet Street advertising agency for the rest of the 1930s, while doing his own drawings and paintings, which he exhibited in both London and Paris.

At the time Adamson met him, Hill was working with the Red Cross Picture Library to loan and lecture on reproductions of paintings to patients in British hospitals to enhance their recovery.

During his early visits to Netherne, Adamson was given several drawings by a man on a locked ward - JJ Beegan - made with the only materials he had, char from burnt matches and toilet paper.

[3] The Medical Superintendent, the psychiatrist Eric Cunningham Dax (1908 - 2008), was impressed by Adamson's rapport at his lectures with the people who were compelled to live at Netherne.

[6] Robertson does not report how many works were created in this period, only referring to "The number of paintings per patient showed extreme variation.

From 1948, Adamson also saw, for two hours each morning, a group of women, on a ward of the main hospital, most of whom had the diagnosis of schizophrenia, and who had all lived in Netherne for many years.

Out of the 1946-1950 quasi-scientific 'experiments', Adamson established an open art studio, allowing people to come and paint freely: a radical act when those detained in the 'asylums' were living in bleak conditions, profoundly excluded from society, with minimum dignity, autonomy or even personal possessions.

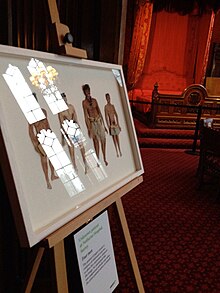

[12] Adamson was more widely involved across the hospital, from having the courage of having endless corridor walls painted primrose yellow to designing costumes for the annual pantomime, a key feature of asylum life in Britain at the time.

Among the artists he encouraged at Netherne were the painter William Kurelek (1927–1977), the sculptor Rolanda Polonsky (1923-1996 - Rolanda preferred Polonska, the Polish feminine spelling of her surname, and she is also known as Polonski but her family have accepted she has become known as 'Polonsky'), for both of whom he secured studios in disused rooms in the hospital; and the illustrator and engraver George Buday (1907–1990), for whom Adamson took over a summerhouse in the grounds of Netherne for his printing press.

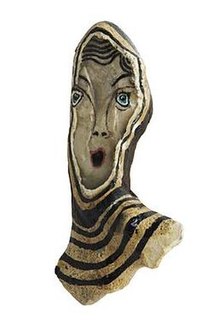

For Polonsky to practise her sculpture, Adamson had to persuade the hospital authorities to lift the restrictions on 'potential offensive weapons in the hands of mental patients' so she could have a hammer and chisel.

They wrote and lectured on art and mental health, and exhibited the Adamson Collection across the world, including Europe, Japan, Canada and the United States.

He was involved from the late 1940s in the discussions and working groups that eventually led to the British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT) in 1964, of which he was a founder member and, briefly, its first Chair.

They were friends and associates with the group of British Jungians who are known as the 'Zurich classical school', as they were almost all trained at the C. G. Jung Institute in Zürich, and emphasised archetypal imagery and its amplification, rather than transference, object relations and early child development.

1933) and Molly Tuby (1917–2011); O'Flynn with Michael Edwards (1930–2010), an influential art therapist, a friend of Adamson and Timlin, on the staff at Withymead and Stanton, and a founder member of the BAAT in 1964 and its Chairman from 1971 to 75.

He was a close friend of Rebecca Alban Hoffberger, and involved as she created the American Visionary Arts Museum (AVAM) in Baltimore.

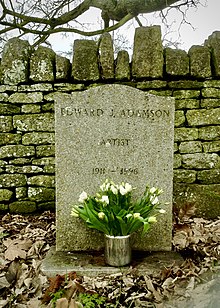

In November 1995 Adamson was advised privately that he was to be awarded the MBE for his services to mental health but he died before this was formally bestowed upon him.

His obituary was published in the New York Times on 10 February 1996 at 'Edward Adamson, 84, Therapist Who Used Art to Aid Mentally Ill' John Timlin died on 11 September 2020, also at the Hollywood Road Studios, aged 90 yrs.

The sub-titles of all these three surveys - particularly 1968's - speak of the attitudes of the time The first two were at the Institute of Contemporary Arts: When Adamson retired from Netherne in 1981, he estimated there were 100,000 objects - paintings, drawings, sculptures and ceramics - in the Collection.

They were chosen by Adamson and Rudolf Freudenberg (a senior psychiatrist and Medical Superintendent at Netherne) for "both artistic and psychiatric interest".

When Adamson and Timlin returned to Netherne later to move the rest of the Collection, it had disappeared, probably destroyed as considered by the hospital authorities to be of no value.

Since 1997, around 300 paintings have hung in corridors in Lambeth Hospital, the Adamson Centre for Mental Health (since it opened in 2000), and a SLaM community base.

The rest of the paintings and drawings were stored either in a disused shower room (seemingly fitting as Adamson's first working space was in a shower room at Netherne), or stacked, unframed, in cardboard folders on shelves in a working team office at Lambeth Hospital, with the two Kureleks wrapped in blankets under a desk.

Between 2007 and 2010, the Adamson Collection Trust employed the then Curator, Alice Jackson, to undertake the Herculean task of cataloguing all the unframed paintings and drawings: they number about 2500 by Polanska - most are preparatory sketches for the "Stations of the Cross" - and another 2500 by over 200 people, more than half of them women.

Adamson's records from Ashton, including albums of press cuttings and coverage, and of examples of Buday's Christmas cards and other prints, were in a filing cabinet.

A series of public consultations in July 2017 explored the complex ethical issues surrounding questions of copyright ownership, attribution and terminology.

By the end of 2024 300 Gwyneth Rowlands' painted flints will be on long-term loan to the new building at Maudsley Hospital, New Douglas Bennett House.

[19] Alongside about 500 small 3-D objects, the work completed at Netherne by the Italian born sculptor, artist and poet Rolanda Polonsky between probably 1948 to 1982 is at the Adamson store at the old Bethlehem museum.

The act of creating was what mattered to Adamson, who felt the artist or therapist should avoid influencing, distorting, or impinging upon self-expression.

Adamson encouraged 'free expression' by letting people come to paint or sculpt without comment or judgement, and with only minimal technical assistance.