Edward R. Hills House

[2][3] The three-story, Stick style home featured tall sash windows topped by bracketed hoods, a covered porch which extended across the front façade, and flared gables filled with decorative, fan-shaped trusses[4] (Historic photo of the exterior prior to 1906).

It was purchased by attorney Nathan Grier Moore, the owner of the large residence on two lots to the immediate north.

As stated in his autobiography, Moore intended to remodel the adjacent house as a future wedding present for his eldest daughter, Mary.

This unusual orientation inconspicuously placed the front door halfway down the north elevation instead of directly facing the street.

The first floor hall was divided into three sections; a small vestibule inside the entrance was followed by a narrow passageway lined by French doors on one side which terminated in an open space with broad doorways into each of the home's principle rooms.

[4] Three dormers – one each on the east, south, and west façades – were likewise faced in shingles and were topped by the same flared, double-pitched roofs.

[16] Existing and new walls, alike, were covered in uniform, lightly textured, pale stucco from the ground up to – and including – the eave soffit.

A cantilevered, rectangular bay, which formed a focal point on the second level of the street (east) elevation, contained a band of four such three-piece windows and was subtly bookended by two deeply inset casements.

Matching porches extended into the front and rear yard on either side of the north-facing, vertical entry and stair tower.

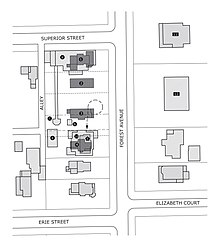

[19] A low concrete wall topped by a similarly short wrought iron fence was incorporated sometime after construction to enclose the yard along the south and east lot lines.

This fence continued along the eastern edge of Nathan Moore's property to the corner of Forest Avenue and Superior Street.

The yard additionally featured an original ticket booth from the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition which Moore had purchased and relocated to the site.

"[12] Sibling Nathan Grier further related that his mother found the entire house too "stern and austere"[4] and she immediately hired neighborhood architect Henry Fiddelke to make alterations.

Since the two yards remained contiguous, the fact that the dividing lot line was tight up against the side of the Hills House posed no problem.

Mary and Edward sold the Moore house the next year, but retained an additional 40 feet (12.2 m) of land to provide space for a side yard and garden north of their home.

[4] Following her husband's death in 1953, Mary Hills continued to reside in the house until she sold it and moved to an apartment in 1965.

[12] In 1975, Tom and Irene DeCaro purchased the house and began a diligent restoration with the aid of architect John Tilton.

The restoration returned the front elevation to its 1906 design yet retained most alterations made by the Hills towards the rear, including the enclosed porches and enlarged kitchen wing.

On the second floor, several walls were moved to widen the hallway and to create a master suite in place of two front bedrooms (see post-reconstruction plans at right).

For their part in the restoration, the Oak Park Landmarks Commission voted in 1977 to rename the completed structure as the Hills-DeCaro House.

In the basement level, the floors were lowered to increase ceiling height and stone foundation walls from the 1884 house were re-exposed.

The determined paint scheme consisted of off-white stucco and wood trim in dark "creosote" brown.

The Smylies and Von Dreel-Freerksen set about recreating the pavilion and the first section of the pergola (the portion which falls within the property lines of the Hills DeCaro House).

[35] However, the cantilevered eaves of the Hills-Decaro house are even deeper – stretching 5.5 feet (1.67 m) on the upper story[5] – and the fascia is even thicker than those of its early predecessors.

When paired with the unique, stepped shingle pattern, these adjustments further accentuate the Prairie style horizontality of the house.