Edward Weston

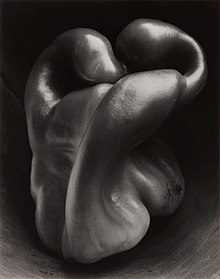

"[2] Over the course of his 40-year career Weston photographed an increasingly expansive set of subjects, including landscapes, still lifes, nudes, portraits, genre scenes, and even whimsical parodies.

She was seven years older than Weston and a distant relative of Harry Chandler, who at that time was described as the head of "the single most powerful family in Southern California".

His sister later asked him why he opened his studio in Tropico rather than in the nearby metropolis of Los Angeles, and he replied "Sis, I'm going to make my name so famous that it won't matter where I live.

He won prizes in national competitions, published several more photographs and wrote articles for magazines such as Photo-Era and American Photography, championing the pictorial style.

Sometime in the fall of 1913, Los Angeles photographer, Margrethe Mather visited Weston's studio because of his growing reputation, and within a few months they developed an intense relationship.

She was very outgoing and artistic in a flamboyant way, and her permissive sexual morals were far different from the conservative Weston at the time – Mather had been a prostitute and was bisexual with a preference for women.

He asked Mather to be his studio assistant, and for the next decade they worked closely together, making individual and jointly signed portraits of writers Carl Sandburg and Max Eastman.

On her own Mather photographed "fans, hands, eggs, melons, waves, bathroom fixtures, seashells and birds wings, all subjects that Weston would also explore.

Over the summer of 1920 Weston met two people who were part of the growing Los Angeles cultural scene: Roubaix de l'Abrie Richey, known as "Robo" and a woman he called his wife, Tina Modotti.

The show was a success, and due in no small part to his nude studies of Modotti, it firmly established Weston's artistic reputation in Mexico.

It's unknown what Flora understood or thought about the relationship between Weston and Modotti, but she is reported to have called out at the dock, "Tina, take good care of my boys.

He wrote in his Daybooks: The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself...I feel definite in the belief that the approach to photography is through realism.

It was there that he learned to fine-tune his photographic vision to match the visual space of his view camera, and the images he took there, of kelp, rocks and wind-blown trees, are among his finest.

It was edited by Merle Armitage and dedicated to Alice Rohrer, an admirer and patron of Weston whose $500 donation helped pay for the book to be published.

During the same time a small group of like-minded photographers in the San Francisco area, led by Van Dyke and Ansel Adams, began informally meeting to discuss their common interest and aesthetics.

The smaller camera allowed him to interact more with his models, while at the same time the nudes he took during this period began to resemble some of the contorted root and vegetables he had taken the year before.

[45] Afterward Dorothea Lange and her husband suggested that the application was too brief to be seriously considered, and Weston resubmitted it with a four-page letter and work plan.

The freedom of this trip with the "love of his life", combined with all of his sons now reaching the age of adulthood, gave Weston the motivation to finally divorce his wife.

Finally relieved from the financial stresses of the past and inordinately happy with his work and his relationship, Weston married Wilson in a small ceremony on April 24.

Weston treated them with the same serious intent that he applied to all of his other subjects, and Charis assembled the results into their most unusual publication, The Cats of Wildcat Hill, which was finally published in 1947.

Weston mentioned he had just that morning written a letter to Ansel Adams, looking for someone seeking to learn photography in exchange for carrying his bulky large-format camera and to provide a much needed automobile.

In early 1948, Dody moved into "Bodie House", the guest cottage at Edward's Wildcat Hill compound, as his full-time assistant.

In 1950 there was a major retrospective of his work at the Musee National d'Art Moderne in Paris, and in 1952 he published a Fiftieth Anniversary portfolio, with images printed by Brett.

Later that same year the Smithsonian Institution displayed nearly 100 of these prints at a major exhibit, "The World of Edward Weston", paying tribute to his accomplishments in American photography.

During the first 20 years of his photography Weston determined all of his exposure settings by estimation based on his previous experiences and the relatively narrow tolerances of the film at that time.

[note 1] Photo historian Nancy Newhall wrote that "Young photographers are confused and amazed when they behold him measuring with his meter every value in the sphere where he intends to work, from the sky to the ground under his feet.

[68] This process was very labor-intensive; he once wrote in his Daybooks "I am utterly exhausted tonight after a whole day in the darkroom, making eight contact negatives from the enlarged positives.

[70][60] Early in his career Weston printed on several kinds of paper, including Velox, Apex, Convira, Defender Velour Black and Haloid.

He first spoke and wrote about the concept in 1922, at least a decade before Ansel Adams began utilizing the term, and he continued to expand upon this idea both in writing and in his teachings.

Although he initially denied that his images reflect his own interpretations of the subject matter, by 1932 his writings revealed that he had come to accept the importance of artistic impression in his work.