Edward the Elder

Edward was admired by medieval chroniclers, and in the view of William of Malmesbury, he was "much inferior to his father in the cultivation of letters" but "incomparably more glorious in the power of his rule".

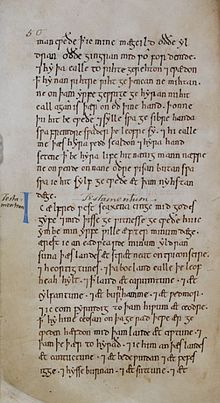

He was largely ignored by modern historians until the 1990s, and Nick Higham described him as "perhaps the most neglected of English kings", partly because few primary sources for his reign survive.

His reputation rose in the late twentieth century and he is now seen as destroying the power of the Vikings in southern England while laying the foundations for a south-centred united English kingdom.

Mercia was the dominant kingdom in southern England in the eighth century and maintained its position until it suffered a decisive defeat by Wessex at the Battle of Ellandun in 825.

Alfred, who was now king, was reduced to a remote base in the Isle of Athelney in Somerset, but the situation was transformed when he won a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington.

The third daughter, Ælfthryth, married Baldwin, Count of Flanders, and the younger son, Æthelweard, was given a scholarly education, including learning Latin.

In his will, he left only a handful of estates to his brother's sons, and the bulk of his property to Edward, including all his booklands (land vested in a charter which could be alienated by the holder, as opposed to folkland, which had to pass to heirs of the body) in Kent.

[9] In a Kentish charter of 898 Edward witnessed as rex Saxonum, suggesting that Alfred may have followed the strategy adopted by his grandfather Egbert of strengthening his son's claim to succeed to the West Saxon throne by making him sub-king of Kent.

The twelfth-century chronicler William of Malmesbury described Ecgwynn as an illustris femina (noble lady), and stated that Edward chose Æthelstan as his heir as king.

[14] The suggestion that Ecgwynn was Edward's mistress is accepted by some historians such as Simon Keynes and Richard Abels,[15] but Yorke and Æthelstan's biographer, Sarah Foot, disagree, arguing that the allegations should be seen in the context of the disputed succession in 924, and were not an issue in the 890s.

These are known only from the late tenth century chronicle of Æthelweard, such as his account of the Battle of Farnham, in which in Nelson's view "Edward's military prowess, and popularity with a following of young warriors, are highlighted."

Towards the end of his life Alfred invested his young grandson Æthelstan in a ceremony which historians see as designation as eventual successor to the kingship.

[a] In 901, Æthelwold came with a fleet to Essex, and the following year he persuaded the East Anglian Danes to invade English Mercia and northern Wessex, where his army looted and then returned home.

Edward retaliated by ravaging East Anglia, but when he retreated the men of Kent disobeyed the order to retire, and were intercepted by the Danish army.

[22] In London in 886, Alfred had received the formal submission of "all the English people that were not under subjection to the Danes", and thereafter he adopted the title Anglorum Saxonum rex (King of the Anglo-Saxons), which is used in his later charters and all but two of Edward's.

[24] This view of Edward's status is accepted by Martin Ryan, who states that Æthelred and Æthelflæd had "a considerable but ultimately subordinate share of royal authority" in English Mercia.

Oswald was translated to a new Mercian minster established by Æthelred and Æthelflæd in Gloucester and the Danes were compelled to accept peace on Edward's terms.

[31] In the following year, the Northumbrian Danes retaliated by raiding Mercia, but on their way home they were met by a combined Mercian and West Saxon army at the Battle of Tettenhall, where the Vikings suffered a disastrous defeat.

The episode suggests that south-east Wales fell within the West Saxon sphere of power, unlike Brycheiniog just to the north, where Mercia was dominant.

The Danes launched unsuccessful attacks on Towcester, Bedford and Wigingamere, while Æthelflæd captured Derby, showing the value of the English defensive measures, which were aided by disunity and a lack of coordination among the Viking armies.

The Danes had built their own fortress at Tempsford in Bedfordshire, but at the end of the summer the English stormed it and killed the last Danish king of East Anglia.

[36] In early 918, Æthelflæd secured the submission of Leicester without a fight, and the Danes of Northumbrian York offered her their allegiance, probably for protection against Norse (Norwegian) Vikings who had invaded Northumbria from Ireland, but she died on 12 June before she could take up the proposal.

There were mints in Bath, Canterbury, Chester, Chichester, Derby, Exeter, Hereford, London, Oxford, Shaftesbury, Shrewsbury, Southampton, Stafford, Wallingford, Wareham, Winchester and probably other towns.

[40] In 908, Plegmund conveyed the alms of the English king and people to the Pope, the first visit to Rome by an Archbishop of Canterbury for almost a century, and the journey may have been to seek papal approval for a proposed re-organisation of the West Saxon sees.

Charters were usually issued when the king made grants of land, and it is possible that Edward followed a policy of retaining property which came into his hands to help finance his campaigns against the Vikings.

[58] Clause 3 of the law code called I Edward provides that people convincingly charged with perjury shall not be allowed to clear themselves by oath, but only by ordeal.

[66] Alfred Smyth points out that Edward was not in a position to impose the same conditions on the Scots and the Northumbrians as he could on conquered Vikings, and argues that the Chronicle presented a treaty between kings as a submission to Wessex.

In his view: Edward continued Æthelflæd's policy of founding burhs in the north-west, at Thelwall and Manchester in 919, and Cledematha (Rhuddlan) at the mouth of the River Clwyd in North Wales in 921.

He died at the royal estate of Farndon, twelve miles south of Chester, on 17 July 924, shortly after putting down the revolt, and was buried in the New Minster, Winchester.

He ruled an expanding realm for twenty-five years and arguably did as much as any other individual to construct a single, south-centred, Anglo-Saxon kingdom, yet posthumously his achievements have been all but forgotten."