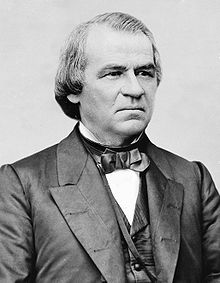

Efforts to impeach Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson became president on April 15, 1865, ascending to the office following the assassination of his presidential predecessor Abraham Lincoln.

While Lincoln had been a Republican, Johnson, his vice president, was a Democrat, the two of them having run on a unity ticket in the 1864 United States presidential election.

Johnson had attempted to stop the federal government from recognizing freed black slaves as citizens, and wanted to take away their civil liberties.

[2] One of the first Radical Republicans to explore impeachment was House Territories Committee chairman James Mitchell Ashley.

[2] Johnson, during a late summer 1866 speaking tour dubbed the "Swing Around the Circle", remarked that some members of Congress would "clamor and talk about impeachment" because he chose to wield his veto power.

[5]By October 1866, Benjamin Butler was traveling to multiple cities delivering speeches in which he promoted the prospect of impeaching Johnson.

The Wisconsin opined that the result of the elections was unequivocally, "in favor of the impeachment of Andrew Johnson and his removal from the high office which he has dishonored.

"[14] Shortly around the time of the November elections 1866, the National Intelligencer alleged that the push to impeach Johnson originated from the tariff lobby.

This claim was challenged by the Chicago Tribune, which wrote, "the movement to impeach Andrew Johnson comes from the people, and not from any lobby, or any set of politicians".

[15] By the end of November 1866, congressman-elect Benjamin Butler was continuing to promote the idea of impeaching Johnson, this time proposing eight articles.

[16] The articles he proposed charged Johnson with: In December 1866, the House Republican caucus met to plan for the lame-duck third session of the 39th United States Congress, which would expire in March 1867.

[2] George S. Boutwell brought up the idea of impeachment during the caucus meeting, but moderates quickly killed discussion.

[2] A number of Radical Republicans were demanding the creation of a select committee to investigate the prospect of impeaching Johnson,[17] On December 17, 1866, James Mitchell Ashley attempted to open a house impeachment inquiry, but his motion to suspend the rules to consider his resolution saw a vote of 88–49, which was short of the needed two-thirds majority to suspend the rules.

[2] Also on January 7, 1867, ignoring the rule requiring approval of the Republican caucus, James Mitchell Ashley introduced his own impeachment-related resolution.

[2] The resulting impeachment inquiry lasted eleven months, saw 89 witnesses interviewed, and saw 1,200 pages of testimony published.

By the time congress' recess ended in late November 1867, attitudes of Republicans had shifted more in favor of impeachment.

[29][30] One motivating factor for Republicans' decision to vote against impeachment may have been the successes Democrats had in the 1867 elections, including winning control of the Ohio General Assembly, as well as other 1867 election outcomes, such as voters in Ohio, Connecticut, and Minnesota turning down propositions to grant African Americans suffrage.

[41] Also on January 21, 1868, a one sentence resolution to impeach Johnson, written by John Covode, was referred to the Select Committee on Reconstruction.

[32][34][47] At 3pm on February 22, Stevens presented from the House Select Committee on Reconstruction a slightly amended version of Covode's resolution along with a report opining that Johnson should be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors.

[52] However, with Johnson's term as president already set to expire on March 4, 1869, most congressmen and senators were disinterested in further pursuing impeachment.