Ancient Egyptian deities

After the founding of the Egyptian state around 3100 BC, the authority to perform these tasks was controlled by the pharaoh, who claimed to be the gods' representative and managed the temples where the rituals were carried out.

One widely accepted definition,[4] suggested by Jan Assmann, says that a deity has a cult, is involved in some aspect of the universe, and is described in mythology or other forms of written tradition.

[29] The goddess Miket, who occasionally appeared in Egyptian texts beginning in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC), may have been adopted from the religion of Nubia to the south, and a Nubian ram deity may have influenced the iconography of Amun.

[31] In Greek and Roman times, from 332 BC to the early centuries AD, deities from across the Mediterranean world were revered in Egypt, but the native gods remained, and they often absorbed the cults of these newcomers into their own worship.

[40] Despite their diverse functions, most gods had an overarching role in common: maintaining maat, the universal order that was a central principle of Egyptian religion and was itself personified as a goddess.

Most prominently, Apep was the force of chaos, constantly threatening to annihilate the order of the universe, and Set was an ambivalent member of divine society who could both fight disorder and foment it.

[46] Richard H. Wilkinson, however, argues that some texts from the late New Kingdom suggest that as beliefs about the god Amun evolved he was thought to approach omniscience and omnipresence, and to transcend the limits of the world in a way that other deities did not.

[50] Over the course of Egyptian history, they came to be regarded as fundamentally inferior members of divine society[51] and to represent the opposite of the beneficial, life-giving major gods.

Periodic occurrences were tied to events in the mythic past; the succession of each new pharaoh, for instance, reenacted Horus's accession to the throne of his father Osiris.

Some poorly understood Egyptian texts even suggest that this calamity is destined to happen—that the creator god will one day dissolve the order of the world, leaving only himself and Osiris amid the primordial chaos.

These deities stood for the plurality of all gods, as well as for their own cult centers (the major cities of Thebes, Heliopolis, and Memphis) and for many threefold sets of concepts in Egyptian religious thought.

[111] Sometimes Set, the patron god of the Nineteenth Dynasty kings[112] and the embodiment of disorder within the world, was added to this group, which emphasized a single coherent vision of the pantheon.

The cult images of gods that were the focus of temple rituals, as well as the sacred animals that represented certain deities, were believed to house divine bas in this way.

Unlike other situations for which this term is used, the Egyptian practice was not meant to fuse competing belief systems, although foreign deities could be syncretized with native ones.

Whereas, in earlier times, newly important gods were integrated into existing religious beliefs, Atenism insisted on a single understanding of the divine that excluded the traditional multiplicity of perspectives.

[144] In the early 20th century, for instance, E. A. Wallis Budge believed that Egyptian commoners were polytheistic, but knowledge of the true monotheistic nature of the religion was reserved for the elite, who wrote the wisdom literature.

[57] Jan Assmann maintains that the notion of a single deity developed slowly through the New Kingdom, beginning with a focus on Amun-Ra as the all-important sun god.

[152] For this reason, the funerary god Anubis is commonly shown in Egyptian art as a dog or jackal, a creature whose scavenging habits threaten the preservation of buried mummies, in an effort to counter this threat and employ it for protection.

Similarly, the clothes worn by anthropomorphic deities in most periods changed little from the styles used in the Old Kingdom: a kilt, false beard, and often a shirt for male gods and a long, tight-fitting dress for goddesses.

[171] Some objects associated with a specific god, like the crossed bows representing Neith (𓋋) or the emblem of Min (𓋉) symbolized the cults of those deities in Predynastic times.

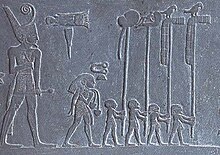

[173] In the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods, gods were often represented by divine standards: poles topped by emblems of deities, including both animal forms and inanimate objects.

Several texts refer to gods influencing or inspiring human decisions, working through a person's "heart"—the seat of emotion and intellect in Egyptian belief.

[205] Morality in ancient Egypt was based on the concept of maat, which, when applied to human society, meant that everyone should live in an orderly way that did not interfere with the well-being of other people.

[212] Beginning in the Middle Kingdom, several texts connected the issue of evil in the world with a myth in which the creator god fights a human rebellion against his rule and then withdraws from the earth.

[221] In Roman times, when local deities of all kinds were believed to have power over the Nile inundation, processions in many communities carried temple images to the riverbanks so the gods could invoke a large and fruitful flood.

Votive offerings and personal names, many of which are theophoric, suggest that commoners felt some connection between themselves and their gods, but firm evidence of devotion to deities became visible only in the New Kingdom, reaching a peak late in that era.

[238] After the end of Egyptian rule there, the imported gods, particularly Amun and Isis, were syncretized with local deities and remained part of the religion of Nubia's independent Kingdom of Kush.

[247] In the empire's complex mix of religious traditions, Thoth was transmuted into the legendary esoteric teacher Hermes Trismegistus,[248] and Isis, who was venerated from Britain to Mesopotamia,[249] became the focus of a Greek-style mystery cult.

[244] Given the great changes and diverse influences in Egyptian culture since that time, scholars disagree about whether any modern Coptic practices are descended from those of pharaonic religion.

[253] In the late 20th century, several new religious groups going under the blanket term of Kemetism have formed based on different reconstructions of ancient Egyptian religion.