Egyptian literature

Not all of the great writers of the period came from outside of Egypt, however; one notable Egyptian poet was Apollonius of Rhodes, so as Nonnus of Panopolis, author of the epic poem Dionysiaca.

Writing first appeared in association with kingship on labels and tags for items found in royal tombs It was primarily an occupation of the scribes, who worked out of the Per Ankh institution or the House of Life.

Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests.

Many stories written in demotic during the Graeco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.

Coptic works were an important contribution to Christian literature of the period and the Nag Hammadi library helped preserve a number of books that would otherwise have been lost.

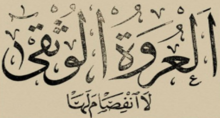

[13] Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī founded a short-lived pan-Islamic revolutionary literary and political journal entitled Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa in 1884.

[15][16] Abduh was a major figure of Islamic modernism,[12] and authored influential works such as Risālat at-Tawḥīd (1897) and published Sharḥ Nahj al-Balagha (1911).

Edwar al-Kharrat, who embodied Egypt's 60s Generation, founded Galerie 68, an Arabic literary magazine that gave voice to avant-garde writers of the time.

Not only had Egypt's population nearly doubled since 1980 with 81 million people in 2008, leading to a rural-urban migration that gave rise to the Arabic term al-madun al-‘ashwa’iyyah, or "haphazard city," around Cairo, but unemployment remained high and living expenses increased amid the overcrowding.

This surge of literary production has led to experimentation with traditional themes, a greater emphasis on the personal, an absence of major political concerns, and a more refined and evolving use of language.

Such small publishing houses, not being state owned, are not influenced by the traditional literary elite and have encouraged new varieties of Egyptian writing.

This resulted in a great deal of critical comment, including a pejorative description of their work as kitabat al-banat or "girls' writing".

Moreover, most novels during this time were relatively short, never much longer than 150 pages, and dealt with the individual instead of a lengthy representation of family relationships and national icons.

Qandil's books, “Red Card for the President” among them, were banned under Mubarak for their strident attacks on the regime — though bootlegged photocopied versions did manage to get here and there.

Humphrey Davies, the English translator of “Metro” and The Yacoubian Building, notes that graphic novels and comics have been immensely popular as well as frequently targeted by censors, because of “the immediacy of their visual impact.” Looking ahead, he added: “How they will be treated by the authorities will be a litmus test for their commitment to freedom of expression.”After the revolution, the former Mubarak Award, the state's top literary prize, has been renamed the Nile Award.

His study called Arab Theology and the Roots of Religious Violence (2010), was one of the more widely read books in Cairo in the months before the January 25 Revolution.