Eichstaettisaurus

With a flattened head, forward-oriented and partially symmetrical feet, and tall claws, Eichstaettisaurus bore many adaptations to a climbing lifestyle approaching those of geckoes.

The type species, E. schroederi, is among the oldest and most complete members of the Squamata, being known by one specimen originating from the Tithonian-aged Solnhofen Limestone of Germany.

Various conflicting positions were found until the advent of analyses incorporating more species and better data, which resolved E. schroederi as a close relative of geckoes in the Gekkonomorpha.

In 1938, Ferdinand Broili described an exquisitely-preserved specimen of lizard, preserved top-side-up, from Jurassic-aged rock deposits in the municipality of Wintershof, Eichstätt, Germany.

[6] Subsequent literature has retained Eichstaettisaurus schroederi and Ardeosaurus digitatellus as separate, although they received little attention until Tiago Simões and colleagues published a redescription of both in 2017.

Despite its poor preservation, the specimen was clearly distinct from the more common lizard in the locality, Meyasaurus; Evans and colleagues suggested that it held affinities to Eichstaettisaurus.

[7] In 2004, Evans and colleagues reported even younger remains of Eichstaettisaurus, which originated from the Albian-aged Pietraroja Plattenkalk in the locality of Pietraroia, which is located in the Matese Mountains of southern Italy.

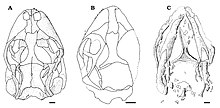

In E. schroederi, the outer edges of the parietals curved inwards, and the rearward projections known as the supratemporal processes were short, widely separated, and bore depressions.

Also in E. schroederi, a pair of crests were present on the supraoccipital bone of the braincase, which were likely imprinted by the semicircular canals due to the skull's reduced ossification.

[2] In E. gouldi, the centra (main bodies) of the tail vertebrae were broad, cylindrical, amphicoelous (concave on both ends), and bore strongly developed transverse processes.

[9][10][11] Based on the well-developed rims of the eye sockets and supratemporal fenestrae on the skull in the type specimen of E. schroederi, Broili concurred with Nopcsa's conclusion in 1938.

[18] Arnau Bolet and Evans conducted two analyses based on Conrad's analysis, for the 2010 and 2012 descriptions of Pedrerasaurus and Jucaraseps, and recovered similar positions for Eichstaettisaurus.

They recovered a more derived position for Eichstaettisaurus as part of the stem group of Gekkota, along with the unnamed specimen AMNH FR 21444; in particular, they noted that its limb proportions strongly resembled gekkotans.

He found Eichstaettisaurus in the same location alongside Norellius, but also recovered A. brevipes as a scincomorph closely related to skinks (in contrast to the stem-gekkotan position of A. digitatellus).

Xantusiidae) Scincidae Topology B: Simões et al. (2018)[22] Megachirella Huehuecuetzpalli Marmoretta Iguanomorpha Eichstaettisaurus Gobekko Gekkota Dibamus Ardeosaurus Paramacellodus Lacertoidea Anguimorpha Xantusiidae Cordyloidea Scincidae Modern geckoes are unusual among lizards in that the digits of their limbs are relatively symmetrical in length, and are splayed in a broad arc; by contrast, the digits in other lizards are usually nearly parallel to each other, especially on the feet.

The pattern seen in geckoes facilitates gripping while the body is in various orientations, since it spreads out the adhesive setae (bristles) on their toepads while allowing the first and last digits to oppose each other.

In 2017, Simões and colleagues observed that E. schroederi had stronger foot symmetry than Ardeosaurus digitatellus, and they inferred that the feet of both were likely directed further forwards than other lizards.

[2] Simões and colleagues also identified several other characteristics in E. schroederi, which suggest that the scansorial (climbing-based) lifestyles of modern geckoes arose earlier than previously appreciated.

[31] Meanwhile, its relatively short limbs and flattened body may have improved climbing performance by lowering its centre of gravity, as has been suggested for the Tokay gecko,[31] but this feature may not be correlated with scansorial lifestyles.

[33] Evans and colleagues found that E. gouldi was closest to the ground-dwelling species, which have slow running speeds and are relatively poor climbers, in its proportions.

They proposed a hybrid lifestyle for E. gouldi: a slow-moving ground lizard with some capacity for climbing on rocks and hiding in crevices from predators like rhynchocephalians.

[4] The rock units at Wintershof that produced the only known specimen of E. schroederi are part of the Solnhofen limestones of southern Germany, which are well known for their exceptionally preserved fossils.

Within the Altmühltal Formation, the Wintershof quarry is part of the Upper Eichstätt Member, which in terms of ammonite biostratigraphy lies in the Euvirgalithacoceras eigeltingense-β horizon between the Lithacoceras riedense and Hybonoticeras hybonotum subzones.

[35][36] The deposits of the Altmühltal Formation, which have been dated to the lower Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period, consist of plattenkalk (very finely-grained limestone-based muds such as micrite) forming even, thin layers measuring about 1 centimetre (0.39 in) thick that generally lack evidence of bioturbation (disturbance by living organisms).

[37][38][39] During the Tithonian, the plattenkalk of the Altmühltal Formation was deposited in oceanic basins (called "wannen") within a warm, shallow sea surrounding an archipelago.

Fossils of bottom-dwelling animals like brittle stars and gastropods are virtually absent, which suggests that conditions at the sea floor were inhospitable to life; this may have been caused by one of several factors including hypersalinity, oxygen depletion, or the accumulation of toxic hydrogen sulfide.

[5] Also known from Wintershof are the pterosaur Rhamphorhynchus muensteri,[44] the crocodyliform Alligatorellus bavaricus,[45] and various aquatic animals: the fish Anaethalion angustus,[46] Ascalabos voithii,[47] Aspidorhynchus acutirostris,[48] Belonostomus spyraenoides,[49] Caturus giganteus,[50] Gyrodus circularis,[51] Macrosemius rostratus, Palaeomacrosemius thiollieri,[52] Propterus elongatus,[53] and Zandtfuro tischlingeri;[54] the angelshark Pseudorhina alifera;[55] the squid-like coleoids Acanthoteuthis problematica,[56] Belemnotheutis mayri,[57] and Plesioteuthis prisca;[58] the crinoid Saccocoma tenella, which is very common in Solnhofen deposits;[59] the shrimp Dusa reschi;[60] and the horseshoe crab Mesolimulus walchi.

[61] Nearby quarries have produced the Eichstätt specimen of the avialan dinosaur Archaeopteryx lithographica,[62] and the pterosaurs Aerodactylus scolopaciceps, Germanodactylus cristatus, and possibly Cycnorhamphus.

The depositional environment was originally thought to have been a lagoon,[65] but it has been re-interpreted as an east-flowing underwater channel that was gradually filled during the Aptian, based on patterns in the arrangement of fossils, the water currents, and the transportation of sediments.

[71] Others include Anaethalion robustus, Belonostomus crassirostris, Caeus leopoldi, Cavinichthys pietrarojae, Chirocentrites coroninii, relatives of Diplomystus brevissimus and Elopopsis fenzii, Hemieloposis gibbus, Ionoscopus petrarojae, Italophiopsis derasmoi, a species of Lepidotes, Notagogus pentlandi, Pleuropholis decastroi, Propterus scacchii, and Sauropsidium laevissimum.