Ekman transport

[1] Ekman transport occurs when ocean surface waters are influenced by the friction force acting on them via the wind.

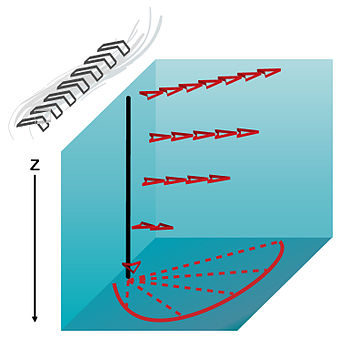

As the wind blows it casts a friction force on the ocean surface that drags the upper 10-100m of the water column with it.

[2] However, due to the influence of the Coriolis effect, the ocean water moves at a 90° angle from the direction of the surface wind.

[3] This phenomenon was first noted by Fridtjof Nansen, who recorded that ice transport appeared to occur at an angle to the wind direction during his Arctic expedition of the 1890s.

Mass conservation, in reference to Ekman transfer, requires that any water displaced within an area must be replenished.

[1] Ekman theory explains the theoretical state of circulation if water currents were driven only by the transfer of momentum from the wind.

In the physical world, this is difficult to observe because of the influences of many simultaneous current driving forces (for example, pressure and density gradients).

Though the following theory technically applies to the idealized situation involving only wind forces, Ekman motion describes the wind-driven portion of circulation seen in the surface layer.

[7] If the ocean is divided vertically into thin layers, the magnitude of the velocity (the speed) decreases from a maximum at the surface until it dissipates.

If all flow over the Ekman layer is integrated, the net transportation is at 90° to the right (left) of the surface wind in the northern (southern) hemisphere.

If the wind moves in a direction causing the water to be pulled away from the coast then Ekman suction will occur.

[9] Returning to the concept of mass conservation, any water displaced by Ekman transport must be replenished.

[9] Ekman suction has major consequences for the biogeochemical processes in the area because it leads to upwelling.

Upwelling carries nutrient rich, and cold deep-sea water to the euphotic zone, promoting phytoplankton blooms and kickstarting an extremely high-productive environment.

[9] As discussed above, the concept of mass conservation requires that a pile up of surface water must be pushed downward.

Downwelling, due to Ekman pumping, leads to nutrient poor waters, therefore reducing the biological productivity of the area.

[1] Specifically, in the subtropics, between 20°N and 50°N, there is Ekman pumping as the tradewinds shift to westerlies causing a pile up of surface water.

A major example of this effect occurs in the Bay of Bengal, where surface flow is offset to the left of wind direction in the Northern Hemisphere.