Ancient Greek funeral and burial practices

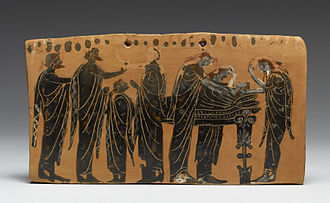

[2] The body of the deceased was prepared to lie in state, followed by a procession to the resting place, a single grave or a family tomb.

[3] Mycenaean cemeteries were located near population centers, with single graves for people of modest means and chamber tombs for elite families.

An exemplary stele depicting a man driving a chariot suggests the esteem in which physical prowess was held in this culture.

This greater simplicity in burial coincided with the rise of democracy and the egalitarian military of the hoplite phalanx, and became pronounced during the early Classical period (5th century BC).

[6] Initiates into mystery religions might be furnished with a gold tablet, sometimes placed on the lips or otherwise positioned with the body, that offered instructions for navigating the afterlife and addressing the rulers of the underworld, Hades and Persephone; the German term Totenpass, "passport for the dead," is sometimes used in modern scholarship for these.

A priest or priestess was not allowed to enter the house of the deceased or to take part in the funerary rites, as death was seen as a cause of spiritual impurity or pollution.

Kinswomen, wrapped in dark robes, stood round the bier, the chief mourner, either mother or wife, was at the head, and others behind.

[8] Since there is a complete absence of any references of animal sacrifices on Attic lêkythoi, this provides the grounds for inferring that the practice as conducted on behalf of ordinary dead was at least very rare.

[8] The mourner first dedicated a lock of hair, along with choai, which were libations of honey, milk, water, wine, perfumes, and oils mixed in varying amounts.

[9] Once the burial was complete, the house and household objects were thoroughly cleansed with seawater and hyssop, and the women most closely related to the dead took part in the ritual washing in clean water.

Although the Greeks developed an elaborate mythology of the underworld, its topography and inhabitants, they and the Romans were unusual in lacking myths that explained how death and rituals for the dead came to exist.

[12] Performing the correct rituals for the dead was essential, however, for assuring their successful passage into the afterlife, and unhappy revenants could be provoked by failures of the living to attend properly to either the rite of passage or continued maintenance through graveside libations and offerings, including hair clippings from the closest survivors.