Khirbet Qeiyafa

[5] It covers nearly 2.3 ha (6 acres) and is encircled by a 700-meter-long (2,300 ft) city wall constructed of field stones, some weighing up to eight tons.

[7] A number of archaeologists, mainly the two excavators, Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor, have claimed that it might be one of two biblical cities, either Sha'arayim, whose name they interpret as "Two Gates", because of the two gates discovered on the site, or Neta'im;[8] and that the large structure at the center is an administrative building dating to the reign of King David, where he might have lodged at some point.

Others suggest it might represent either a North Israelite, Philistine, or Canaanite fortress, a claim rejected by the archaeological team that excavated the site.

[20] In the Byzantine period, a luxurious land villa was built on top of the Iron Age II palace and cut the older structure in two.

[23] The modern Hebrew name, מבצר האלה, or the Elah Fortress was suggested by Foundation Stone directors David Willner and Barnea Levi Selavan at a meeting with Garfinkel and Ganor in early 2008.

The name derives from the location of the site on the northern bank of Nahal Elah, one of six brooks that flow from the Judean mountains to the coastal plain.

[22] The Elah Fortress lies just inside a north-south ridge of hills separating Philistia and Gath to the west from Judea to the east.

[4] Excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa began in 2007, directed by Yosef Garfinkel of the Hebrew University and Saar Ganor of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and continued in 2008.

[28] The initial excavation by Ganor and Garfinkel took place from August 12 to 26, 2007 on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Institute of Archaeology.

In their preliminary report at the annual ASOR conference on November 15, they presented a theory that the site was the Biblical Azekah, which until then had been exclusively associated with Tell Zakariya.

[32] Discoveries at Khirbet Qeiyafa are significant to the debate on archaeological evidence and historicity of the biblical account of the United Monarchy at the beginning of Iron Age II.

Finkelstein and Alexander Fantalkin, maintained that the site shows affiliations with a North Israelite entity saying that "There is no evidence for arguing that Jerusalem, Hebron and Khirbet Qeiyafa were the main centres of 10th century Judah.

[34] In 2015 Finkelstein and Piasetsky specifically criticised the previous statistical treatment of radio-carbon dating at Khirbet Qeiyafa and also whether it was prudent to ignore results from neighboring sites.

[35] Archeologists, Yosef Garfinkel, Mitka R. Golub, Haggai Misgav, and Saar Ganor rejected in 2019 the possibility that Khirbet Qeiyafa could be associated with the Philistines.

Dagan believes the ancient Philistine retreat route, after their defeat in the battle at the Valley of Elah (1 Samuel 17:52), more likely identifies Sha'arayim with the remains of Khirbet esh-Shari'a.

[39][40][41] Based on pottery finds at Qeiyafa and Gath, archaeologists believe the sites belonged to two distinct ethnic groups.

The nature of the ceramic shards found at the site suggest residents might have been neither Israelites nor Philistines but members of a third, forgotten people.

[47] Levin argues that the story of David and Goliath is set decades before Khirbet Qeiyafa was built and so the reference to Israel's encampment at the ma'gal probably does "not represent any particular historical event at all".

[47] Garfinkel and his colleagues have suggested that the identification with the ma'gal is unconvincing as the term is used to refer to a military camp/outpost, whereas Khirbet Qeiyafa was a fortified city.

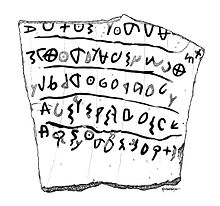

[48] Benyamin Saas, Professor of Archaeology at Tel Aviv university,[49] analyzed the dating, ethnic and political affiliation of Khirbet Qeiyafa as well as the language of the ostracon.

"A dating in the Iron I–II transition, the mid 10th century, assuming the alphabet has just begun its move out of Philistia then could just make a Jerusalem link and Judahite Hebrew language possible for the ostracon.

These two fortification phases rise to a height of 2–3 meters and standout at a distance, evidence of the great effort that was invested in fortifying the place.

He suggested "that the population of Khirbet Qeiyafa observed at least two biblical bans, on pork and on graven images, and thus practiced a different cult than that of the Canaanites or the Philistines.

[58] On July 18, 2013, the Israel Antiquities Authority issued a press release about the discovery of a structure believed to be King David's palace in the Judean Shephelah.

The claim that the larger structure may be one of King David's palaces led to significant media coverage, while skeptics accused the archaeologists of sensationalism.

[59] Aren Maeir, an archaeologist at Bar Ilan University, pointed out that existence of King David's monarchy is still unproven and some scholars believe the buildings could be Philistine or Canaanite.