Election

[2] The Pala King Gopala (ruled c. 750s – 770s CE) in early medieval Bengal was elected by a group of feudal chieftains.

[3][4] In the Chola Empire, around 920 CE, in Uthiramerur (in present-day Tamil Nadu), palm leaves were used for selecting the village committee members.

Nor were the lowest of the four classes of Athenian citizens (as defined by the extent of their wealth and property, rather than by birth) eligible to hold public office, through the reforms of Solon.

[2] Despite legally mandated universal suffrage for adult males, political barriers were sometimes erected to prevent fair access to elections (see civil rights movement).

Elections with an electorate in the hundred thousands appeared in the final decades of the Roman Republic, by extending voting rights to citizens outside of Rome with the Lex Julia of 90 BC, reaching an electorate of 910,000 and estimated voter turnout of maximum 10% in 70 BC,[17] only again comparable in size to the first elections of the United States.

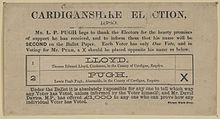

The secret ballot is a relatively modern development, but it is now considered crucial in most free and fair elections, as it limits the effectiveness of intimidation.

[21] The nature of democracy is that elected officials are accountable to the people, and they must return to the voters at prescribed intervals to seek their mandate to continue in office.

They tend to greatly lengthen campaigns, and make dissolving the legislature (parliamentary system) more problematic if the date should happen to fall at a time when dissolution is inconvenient (e.g. when war breaks out).

Other states (e.g., the United Kingdom) only set maximum time in office, and the executive decides exactly when within that limit it will actually go to the polls.

In practice, this means the government remains in power for close to its full term, and chooses an election date it calculates to be in its best interests (unless something special happens, such as a motion of no-confidence).

In many of the countries with weak rule of law, the most common reason why elections do not meet international standards of being "free and fair" is interference from the incumbent government.

[2] Non-governmental entities can also interfere with elections, through physical force, verbal intimidation, or fraud, which can result in improper casting or counting of votes.

[23] In 2018 the most intense interventions, utilizing false information, were by China in Taiwan and by Russia in Latvia; the next highest levels were in Bahrain, Qatar and Hungary.

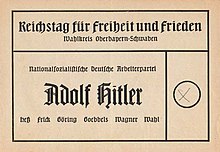

Published results usually show nearly 100% voter turnout and high support (typically at least 80%, and close to 100% in many cases) for the prescribed candidates or for the referendum choice that favours the political party in power.

[33][34] Sham elections can sometimes backfire against the party in power, especially if the regime believes they are popular enough to win without coercion, fraud or suppressing the opposition.

King of Liberia was reported to have won by 234,000 votes in the 1927 general election, a "majority" that was over fifteen times larger than the number of eligible voters.

[38] Some scholars argue that the predominance of elections in modern liberal democracies masks the fact that they are actually aristocratic selection mechanisms[39] that deny each citizen an equal chance of holding public office.

[40] These four factors result in the evaluation of candidates based on voters' partial standards of quality and social saliency (for example, skin colour and good looks).

This leads to self-selection biases in candidate pools due to unobjective standards of treatment by voters and the costs (barriers to entry) associated with raising one's political profile.

Ultimately, the result is the election of candidates who are superior (whether in actuality or as perceived within a cultural context) and objectively unlike the voters they are supposed to represent.

[41] Prior to the 18th century, some societies in Western Europe used sortition as a means to select rulers, a method which allowed regular citizens to exercise power, in keeping with understandings of democracy at the time.

On the other hand, elections began to be seen as a way for the masses to express popular consent repeatedly, resulting in the triumph of the electoral process until the present day.

[44] Those in favor of this view argue that the modern system of elections was never meant to give ordinary citizens the chance to exercise power - merely privileging their right to consent to those who rule.

[39][46][47] To deal with this issue, various scholars have proposed alternative models of democracy, many of which include a return to sortition-based selection mechanisms.

The extent to which sortition should be the dominant mode of selecting rulers[46] or instead be hybridised with electoral representation[48] remains a topic of debate.