Electoral system

The field has produced several major results, including Arrow's impossibility theorem (showing that ranked voting cannot eliminate the spoiler effect) and Gibbard's theorem (showing it is impossible to design a straightforward voting system, i.e. one where it is always obvious to a strategic voter which ballot they should cast).

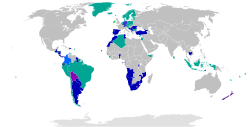

In cases where there is a single position to be filled, it is known as first-past-the-post; this is the second most common electoral system for national legislatures, with 58 countries using it for this purpose,[1] the vast majority of which are current or former British or American colonies or territories.

In social choice theory, runoff systems are not called majority voting, as this term refers to Condorcet-methods.

Party-list proportional representation is the single most common electoral system and is used by 80 countries, and involves voters voting for a list of candidates proposed by a party.

In some countries, notably Israel and the Netherlands, elections are carried out using 'pure' proportional representation, with the votes tallied on a national level before assigning seats to parties.

Primary elections limit the risk of vote splitting by ensuring a single party candidate.

Some proportional systems that may be used with either ranking or rating include the Method of Equal Shares and the Expanding Approvals Rule.

Most countries's electorates are characterised by universal suffrage, but there are differences on the age at which people are allowed to vote, with the youngest being 16 and the oldest 21.

Political parties may seek to gain an advantage during redistricting by ensuring their voter base has a majority in as many constituencies as possible, a process known as gerrymandering.

Historically rotten and pocket boroughs, constituencies with unusually small populations, were used by wealthy families to gain parliamentary representation.

[15] Reserved seats are used in many countries to ensure representation for ethnic minorities, women, young people or the disabled.

[17] In ancient Greece and Italy, the institution of suffrage already existed in a rudimentary form at the outset of the historical period.

In the early monarchies it was customary for the king to invite pronouncements of his people on matters in which it was prudent to secure its assent beforehand.

In these assemblies the people recorded their opinion by clamouring (a method which survived in Sparta as late as the 4th century BCE), or by the clashing of spears on shields.

However, in Athenian democracy, voting was seen as the least democratic among methods used for selecting public officials, and was little used, because elections were believed to inherently favor the wealthy and well-known over average citizens.

The practice of the Athenians, which is shown by inscriptions to have been widely followed in the other states of Greece, was to hold a show of hands, except on questions affecting the status of individuals: these latter, which included all lawsuits and proposals of ostracism, in which voters chose the citizen they most wanted to exile for ten years, were determined by secret ballot (one of the earliest recorded elections in Athens was a plurality vote that it was undesirable to win, namely an ostracism vote).

Hence a series of laws enacted between 139 and 107 BCE prescribed the use of the ballot (tabella), a slip of wood coated with wax, for all business done in the assemblies of the people.

Despite its complexity, the method had certain desirable properties such as being hard to game and ensuring that the winner reflected the opinions of both majority and minority factions.

[20] This process, with slight modifications, was central to the politics of the Republic of Venice throughout its remarkable lifespan of over 500 years, from 1268 to 1797.

However, recent research has shown that the philosopher Ramon Llull devised both the Borda count and a pairwise method that satisfied the Condorcet criterion in the 13th century.

[22] A variety of methods were proposed by statesmen such as Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and Daniel Webster.

[22] The single transferable vote (STV) method was devised by Carl Andræ in Denmark in 1855 and in the United Kingdom by Thomas Hare in 1857.

[24] Perhaps influenced by the rapid development of multiple-winner electoral systems, theorists began to publish new findings about single-winner methods in the late 19th century.

This began around 1870, when William Robert Ware proposed applying STV to single-winner elections, yielding instant-runoff voting (IRV).

[26] Ranked voting electoral systems eventually gathered enough support to be adopted for use in government elections.

However, a series of court decisions ruled Bucklin to be unconstitutional, while supplementary voting was soon repealed in every city that had implemented it.

Earlier developments such as Arrow's impossibility theorem had already shown the issues with ranked voting systems.

Research led Steven Brams and Peter Fishburn to formally define and promote the use of approval voting in 1977.

Studies have found voter satisfaction with IRV tends to fall dramatically the first time a race produces a result different from first-past-the-post.

[41] The United Kingdom used instant-runoff voting for most local elections up until 2022, before returning to first-past-the-post over concerns regarding the system's complexity.

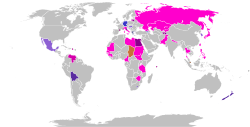

Compensatory

Compulsory voting, not enforced

Compulsory voting, enforced (only men)

Compulsory voting, not enforced (only men)

Historical: the country had compulsory voting in the past.