Electroweak interaction

Above the unification energy, on the order of 246 GeV,[a] they would merge into a single force.

It is thought that the required temperature of 1015 K has not been seen widely throughout the universe since before the quark epoch, and currently the highest human-made temperature in thermal equilibrium is around 5.5×1012 K (from the Large Hadron Collider).

Sheldon Glashow,[1] Abdus Salam,[2] and Steven Weinberg[3] were awarded the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for their contributions to the unification of the weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, known as the Weinberg–Salam theory.

[4][5] The existence of the electroweak interactions was experimentally established in two stages, the first being the discovery of neutral currents in neutrino scattering by the Gargamelle collaboration in 1973, and the second in 1983 by the UA1 and the UA2 collaborations that involved the discovery of the W and Z gauge bosons in proton–antiproton collisions at the converted Super Proton Synchrotron.

In 1999, Gerardus 't Hooft and Martinus Veltman were awarded the Nobel prize for showing that the electroweak theory is renormalizable.

After the Wu experiment in 1956 discovered parity violation in the weak interaction, a search began for a way to relate the weak and electromagnetic interactions.

Extending his doctoral advisor Julian Schwinger's work, Sheldon Glashow first experimented with introducing two different symmetries, one chiral and one achiral, and combined them such that their overall symmetry was unbroken.

This did not yield a renormalizable theory, and its gauge symmetry had to be broken by hand as no spontaneous mechanism was known, but it predicted a new particle, the Z boson.

In 1964, Salam and John Clive Ward[6] had the same idea, but predicted a massless photon and three massive gauge bosons with a manually broken symmetry.

Later around 1967, while investigating spontaneous symmetry breaking, Weinberg found a set of symmetries predicting a massless, neutral gauge boson.

Initially rejecting such a particle as useless, he later realized his symmetries produced the electroweak force, and he proceeded to predict rough masses for the W and Z bosons.

Mathematically, electromagnetism is unified with the weak interactions as a Yang–Mills field with an SU(2) × U(1) gauge group, which describes the formal operations that can be applied to the electroweak gauge fields without changing the dynamics of the system.

These are not physical fields yet, before spontaneous symmetry breaking and the associated Higgs mechanism.

In the Standard Model, the observed physical particles, the W± and Z0 bosons, and the photon, are produced through the spontaneous symmetry breaking of the electroweak symmetry SU(2) × U(1)Y to U(1)em,[b] effected by the Higgs mechanism (see also Higgs boson), an elaborate quantum-field-theoretic phenomenon that "spontaneously" alters the realization of the symmetry and rearranges degrees of freedom.

That is to say: the Higgs and the electromagnetic field have no effect on each other, at the level of the fundamental forces ("tree level"), while any other combination of the hypercharge and the weak isospin must interact with the Higgs.

This causes an apparent separation between the weak force, which interacts with the Higgs, and electromagnetism, which does not.

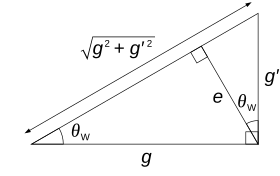

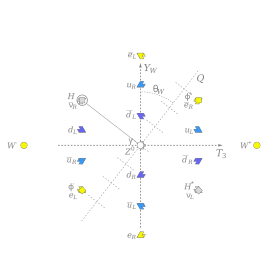

Mathematically, the electric charge is a specific combination of the hypercharge and T3 outlined in the figure.

The axes representing the particles have essentially just been rotated, in the (W3, B) plane, by the angle θW.

This also introduces a mismatch between the mass of the Z0 and the mass of the W± particles (denoted as mZ and mW, respectively), The W1 and W2 bosons, in turn, combine to produce the charged massive bosons W±:[12] The Lagrangian for the electroweak interactions is divided into four parts before electroweak symmetry breaking becomes manifest, The

The interaction of the gauge bosons and the fermions are through the gauge covariant derivative, where the subscript j sums over the three generations of fermions; Q, u, and d are the left-handed doublet, right-handed singlet up, and right handed singlet down quark fields; and L and e are the left-handed doublet and right-handed singlet electron fields.

means the contraction of the 4-gradient with the Dirac matrices, defined as and the covariant derivative (excluding the gluon gauge field for the strong interaction) is defined as Here

term describes the Yukawa interaction with the fermions, and generates their masses, manifest when the Higgs field acquires a nonzero vacuum expectation value, discussed next.

The Lagrangian reorganizes itself as the Higgs field acquires a non-vanishing vacuum expectation value dictated by the potential of the previous section.

In the history of the universe, this is believed to have happened shortly after the hot big bang, when the universe was at a temperature 159.5±1.5 GeV[13] (assuming the Standard Model of particle physics).

Due to its complexity, this Lagrangian is best described by breaking it up into several parts as follows.

contains all the quadratic terms of the Lagrangian, which include the dynamic terms (the partial derivatives) and the mass terms (conspicuously absent from the Lagrangian before symmetry breaking) where the sum runs over all the fermions of the theory (quarks and leptons), and the fields

components of the Lagrangian contain the interactions between the fermions and gauge bosons, where

is the right-handed singlet neutrino field, and the CKM matrix

determines the mixing between mass and weak eigenstates of the quarks.

contains the Higgs interactions with gauge vector bosons,

W

and

Z

bosons.