Elena Bacaloglu

[2] Alexandru and Sofia's children, other than Elena, were: Constantin (1871–1942), a University of Iași physician; Victor (1872–1945), an engineer, writer and journalist; and George (Gheorghe) Bacaloglu, an artillery officer and literary man.

[26] Having traveled through much of Western Europe,[6] she spent most of her time in Italy, writing articles for Il Giornale d'Italia, Madame, and the political magazine L'Idea Nazionale.

[28] In the early 1910s, Bacaloglu was living in Rome, where, in September 1912, she published a monograph about the love affair between Romanian poet Gheorghe Asachi and his Italian muse, Bianca Milesi.

[29] A recipient of the Bene Merenti medal, granted by the Romanian King Carol I,[30] she translated into French the prose work of his consort, Carmen Sylva.

[13] Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, Bacaloglu turned to political activism and interventionism, campaigning for still-neutral Romania to join the Entente Powers, and supporting the annexation of Romanian-inhabited Transylvania.

[35] Working for this organization, she became close to Italian General Luigi Cadorna, described by Romanian officials as her "protector",[36] and Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino.

[30] Her efforts to popularize the Romanian cause among the troops fighting on the northern Italian front were interrupted in October 1917 by the Battle of Caporetto, which Italy lost, forcing Bacaloglu to take refuge in Genoa.

[38] The cause of "Greater Romania" fascinated two of Bacaloglu's three brothers: Victor, the author of patriotic plays,[39] created one of the first all-Romanian newspapers in Bessarabia; George fought with distinction during the war of 1916, fulfilled several diplomatic missions, and was later a Prefect of Bihor County, Transylvania.

[42] One of the first Romanians to gain familiarity with the modern far-right movements in Europe, and, historians assess, driven by an "enormous ambition",[43] she contemplated transplanting Italian fascism into Greater Romania.

This project had preoccupied her since the "red biennium" of 1919–1920, when she presented a proto-fascist appeal to the Italian nationalist Gabriele d'Annunzio[44] and wrote articles for Il Popolo d'Italia.

[44] She also addressed Italian journalists Giuseppe Bottai and Piero Bolzon, who agreed to become members of Bacaloglu's Romanian fascist steering committee.

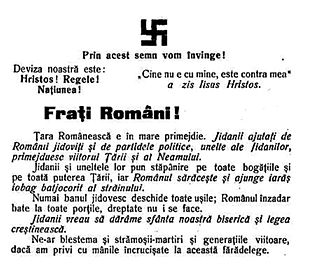

[51] The main difference between the Italian and Romanian fascists was their respective stance on the "Jewish Question": the Italo-Romanian Movement was antisemitic; the original Fasci were not.

Working with the antisemitic opinion leader, A. C. Cuza, he gave endorsement to rioters who called for the expulsion of most Romanian Jewish students, and tolerated fascist symbolism.

[53] However, according to political scientist Emanuela Costantini, the antisemitic agenda of the Movement was comparatively "moderate"; she highlights instead Bacaloglu's other ideas: "an anti-industrialism in the populist mold", and a version of nationalism heavily inspired by the Action Française.

[58] Only about a hundred people were persuaded to join,[59] even though, as historian Francisco Veiga notes, many represented the more active strata of Romanian society (soldiers, students).

[61] Women themselves were largely absent: still not granted the vote under the 1923 Constitution, they generally preferred enrollment in specifically feminist organizations, and were never popular with the more significant Romanian fascist parties (including, from 1927, the Iron Guard).

She believed that the Little Entente, which was partly dedicated to countering Italian irredentism but included Romania, would leave the two countries prey to capitalist and Jewish exploitation.

Codreanu had attempted to assassinate the staff of Adevărul, including the Jewish manager Iacob Rosenthal, and, during the interrogations, implicated other fascist alliances.

[68] According to historian Armin Heinen, the MNFIR was never a fully fledged party, whereas Vifor's more powerful movement could present a more attractive platform to some of Bacaloglu's disillusioned followers.

Sandi Bacaloglu signed his name to the appeal as a Fascio representative, and became a member of the LANC's executive council, on par with Ioan Moța, Ion Zelea Codreanu, Iuliu Hațieganu, Valeriu Pop, Iuniu Lecca.

She claimed that the authorities still owed her some 4 million Lei, which she tried to obtain from Interior Affairs Minister Octavian Goga and from Writers' Society president Liviu Rebreanu.

In her letters to Rebreanu, she made transparent allusions to the possibility of mutual help but, researcher Andrei Moldovan suggests, was incoherent and needlessly haughty.

[83] Also in 1929, the Romanian fascio was revived a third and final time, when a certain Colonel August Stoica tried to use it in his coup against government, variously described as an "operatic plot"[52] or a "shambolic conspiracy".

[85] Bacaloglu herself remained active on the margin of Romanian politics, witnessing from the side as Prince Carol retook his throne with the help of Iuliu Maniu and the National Peasants' Party.

In 1931, she claimed that a conspiracy, headed by diplomat Filip Lahovary and the leaders of the National Liberal Party, wanted to assassinate her "through hunger" and prevented her from even talking to people of influence.

[88] Sandi Bacaloglu carried on a LANC activist and then joined the successor National Christian Party (PNC), running in the legislative election of 1937 in Bucharest's Black Sector.

[92] He adhered to his mother and uncle's fascist ideology: he was a staff writer for the Iron Guard paper Porunca Vremii, translated the political essays of Mussolini and Antonio Beltramelli, and campaigned in support of Italy during the Ethiopian War.

He was assigned by the Iron Guard's "National Legionary State" to direct the Romanian Propaganda Office in Rome, together with writers Aron Cotruș and Vintilă Horia,[97] and, in May 1941, became its president.

[8][30] She maintained friendly contacts with the left-leaning writer Gala Galaction, but nevertheless lived to see the effects of political retaliation and recession on the Bacaloglu family: her daughter by Rosetti was sacked from her government job.

[2] She was survived by Ovid Jr. After the official establishment of Communist Romania, he focused on his work as a philologist, but was still arrested in 1958, and spent six years as a political prisoner.