Elgin Marbles

On 26 September 1687, a Venetian artillery round ignited the gunpowder, and the resulting explosion blew out the central portion of the Parthenon and caused the cella's walls to crumble into rubble.

[21][22] In November 1798, the Earl of Elgin was appointed as "Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Britannic Majesty to the Sublime Porte of Selim III, Sultan of Turkey" (Greece was then part of the Ottoman Empire).

"[6] Elgin decided to carry out the work himself, and employed artists to take casts and drawings under the supervision of the Neapolitan court painter, Giovanni Lusieri.

According to a Turkish local, marble sculptures that fell were being burned to obtain lime for building, and comparison with previously published drawings documented the state of rapid decay of the remains.

[28] The following years marked an increased interest in classical Greece, and Elgin procured testimonials from Ennio Quirino Visconti, director of the Louvre, and Antonio Canova of the Vatican Museum, who affirmed the high artistic value of the marbles.

[29] In 1816, a House of Commons Select Committee, established at Lord Elgin's request, found that they were of high artistic value and recommended that the government purchase them for £35,000 to further the cultivation of the fine arts in Britain.

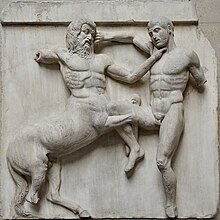

[32] The marbles acquired by Elgin include some 21 figures from the statuary from the east and west pediments, 15 of an original 92 metope panels depicting battles between the Lapiths and the centaurs, as well as 75 metres of the Parthenon frieze which decorated the horizontal course set above the interior architrave of the temple.

[33] The British Museum also holds additional fragments from the Acropolis, acquired from various collections without connection to Elgin, such as those of Léon-Jean-Joseph Dubois,[34] William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire,[35] and the Society of Dilettanti.

[30] In his evidence to the committee,[37] Elgin stated that the work of his agents at the Acropolis, and the removal of the marbles, were authorised by a firman (a generic term employed by Western travellers to signify any official Ottoman order) from the Ottoman government obtained in July 1801, and was undertaken with the approval of the voivode (civil governor of Athens) and the dizdar (military commander of the Acropolis citadel).

[41][42] The document states in part,[43] that it be written and ordered that the said painters [Elgin's men] while they are occupied in entering and leaving by the gate of the Castle of the City, which is the place for their observations, in setting up scaffolding round the ancient temple of the Idols [the Parthenon], and taking moulds in lime paste (that is plaster) of the same ornaments, and visible figures, in measuring the remains of other ruined buildings, and in undertaking to excavate, according to need, the foundations to find any inscribed blocks, which may have been preserved in the rubble, be not disturbed, nor in any way impeded by the Commandant of the Castle, nor any other person, and that no one meddle with their scaffolding, and implements, which they may have made there; and should they wish to take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions, and figures, that no opposition be made.Vassilis Demetriades, of the University of Crete, argues that the document is not a firman (a decree from the Sultan), or a buyuruldi (an order from the Grand Vizier), but a mektub (official letter) from the Sultan's acting Grand Vizier which did not have the force of law.

Demetriades, David Rudenstine and others argue that the document only authorised Elgin's party to remove artefacts recovered from the permitted excavations, not those still attached to buildings.

[44][47] Williams argues that the document was "rather open ended" and that the civil governor agreed with Hunt's interpretation that it allowed Elgin's party to remove sculptures fixed to buildings.

[50] Legal academic Catharine Titi states that Sir Robert Adair reported that the Ottomans in 1811 "absolutely denied" that Elgin had any property in the sculptures.

[51] Legal scholar Alexander Herman and historian Edhem Eldem state that documents in the Turkish archives show that this denial was only a delaying tactic for reasons of diplomacy, and that the Porte eventually granted permission for the transport of the marbles to Britain later in 1811.

[52][53] A number of eyewitnesses to the removal of the marbles from the Acropolis, including members of Elgin's party, stated that expensive bribes and gifts to local officials were required to ensure their work progressed.

"[60] In response, archaeologist Mario Trabucco della Torretta states that scholars consider that the British copy of the firman is genuine and that it is arguable that it did grant Elgin permission to remove the sculptures.

[64] Classicist Richard Payne Knight, however, declared they were Roman additions or the work of inferior craftsmen, and painter Ozias Humphrey called them "a mass of ruins".

It was, it seems, fatal that a representative of our country loot those objects that the Turks and other barbarians had considered sacred.Edward Daniel Clarke witnessed the removal of the metopes and called the action a "spoliation", writing that "thus the form of the temple has sustained a greater injury than it had already experienced from the Venetian artillery", and that "neither was there a workman employed in the undertaking ... who did not express his concern that such havoc should be deemed necessary, after moulds and casts had been already made of all the sculpture which it was designed to remove.

"[54] When Sir Francis Ronalds visited Athens and Giovanni Battista Lusieri in 1820, he wrote that "If Lord Elgin had possessed real taste in lieu of a covetous spirit he would have done just the reverse of what he has, he would have removed the rubbish and left the antiquities.

"[68][69] In 1810, Elgin published a defence of his actions, in which he argued that he had only decided to remove the marbles when he realised that they were not being cared for by Ottoman officials and were in danger of falling into the hands of Napoleon's army.

[70][71] Felicia Hemans supported the purchase of the marbles and in her Modern Greece: A Poem (1817), defied Byron with the question: And who may grieve that, rescued from their hands, Spoilers of excellence and foes of art, Thy relics, Athens!

[6] To facilitate transport by Elgin, the columns' capitals and many metopes and frieze slabs were either hacked off the main structure or sawn and sliced into smaller sections, causing irreparable damage to the Parthenon itself.

[82][83] One shipload of marbles on board the British brig Mentor[84] was caught in a storm off Cape Matapan in southern Greece and sank near Kythera, but was salvaged at the Earl's personal expense;[85] it took two years to bring them to the surface.

The use of fine, gritty powder, with the water and rubbing, though it more quickly removed the upper dirt, left much embedded in the cellular surface of the marble.

Richard Westmacott, who was appointed superintendent of the "moving and cleaning the sculptures" in 1857, in a letter approved by the British Museum Standing Committee on 13 March 1858 concluded[90]

[96] In a newspaper article, American archaeologist Dorothy King wrote that techniques similar to those used in 1937–1938 were applied by Greeks as well in more recent decades than the British, and maintained that Italians still find them acceptable.

[97] The British Museum said that a similar cleaning of the Temple of Hephaestus in the Athenian Agora was carried out by the conservation team of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens[98] in 1953 using steel chisels and brass wire.

[96] The 1953 American report concluded that the techniques applied were aimed at removing the black deposit formed by rain-water and "brought out the high technical quality of the carving" revealing at the same time "a few surviving particles of colour".

In 1836, King Otto of the newly independent Greece, formally asked the British government to return some of the Elgin Marbles (the four slabs of the frieze of the Temple of Athena Nike).

The committee heard evidence from the then Greek foreign minister, George Papandreou, who argued that the question of legal ownership was secondary to the ethical and cultural arguments for returning the sculptures.