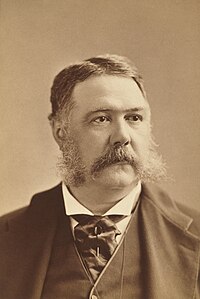

Elihu Root

He modernized the consular service by minimizing patronage, maintained the Open Door Policy in China, promoted friendly relations with Latin America, and resolved frictions with Japan over the immigration and treatment of Japanese citizens to the West Coast of the United States.

[5] Root supported Wilson's vision of the League of Nations but with reservations along the lines proposed by Republican senator Henry Cabot Lodge.

[12] His early work was assorted and menial, but expanded rapidly after he met John J. Donaldson, the president of the Bank of North America, through their pastor.

Donaldson hired Root as a Latin tutor and was impressed with his ability as a lawyer, eventually sending him personal matters and small cases for the Bank.

[15] Through 1899, Root took on many other prominent and wealthy clients, including Jay Gould, Chester A. Arthur, Charles Anderson Dana, William C. Whitney, Thomas Fortune Ryan, the Havemeyer family, Charlie Delmonico, and E. H.

In December 1871, Tammany Hall boss William M. Tweed was indicted on charges of deceit and fraud in connection to his real estate dealings and political corruption.

The jury returned a guilty verdict on two hundred and four counts; Davis imposed a sentence of twelve years and a $12,750 fine, later reduced on appeal.

"[14] Nevertheless, after his 1878 marriage and move to East 55th Street, Root became actively involved in the Republican Party organization in his well-to-do State Assembly district.

[22][23] There was limited opposition to his nomination given that Arthur was trying to force out a political rival, Stewart L. Woodford, who had been appointed by Garfield, but he was approved by the Senate and sworn in on March 12.

The cross-examination of the defendant was characterized by exceptional acumen and professional skill, and was made much more effective than it would otherwise have been by Mr. Root's evident familiarity with the details of the banking business."

In particular, Root was credited with vindicating the late President: "The unspeakable meanness of the conspirators in trying to save themselves by implicating General Grant in their fraudulent transactions... was dealt with in terms of deserved scorn and severity by the District Attorney.

"[25] As Secretary of War, Root actively framed the establishment of civilian governments in the new American territories of Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico.

To that end, he enlarged the United States Military Academy and established the U.S. Army War College and additional training posts, especially Fort Leavenworth.

[29] He worked out the procedures for turning Cuba over to the Cubans, ensured a charter of government for the Philippines, and eliminated tariffs on goods imported to the United States from Puerto Rico.

[30] Magoon had been hired at the Bureau of Insular Affairs by Root's predecessor, Russell Alger, and drafted an internal report taking the official position that residents of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and other territories became subject to all the rights granted by the Constitution.

[33] Root's primary goal was the establishment of a civilian governor-general (as had been applied in Cuba) rather than a military governor; however, he felt that education of the native population was necessary before such a transition could be successful.

[33] In addition to his duties as Secretary of War, Root was one of three Americans appointed by President Roosevelt (with Henry Cabot Lodge and George Turner) to an international arbitration court to resolve the boundary dispute between Alaska and Great Britain.

[34] On October 20, 1903, the dispute was resolved by British jurist Richard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone in favor of the United States on every point of contention.

[35] He also repeatedly refused efforts to draft him as the Republican candidate for Governor in the 1904 election; instead, he focused on securing Roosevelt's nomination to a full term at the national convention, where he delivered the opening speech.

He worked with Great Britain in arbitration of issues between the United States and Canada on the Alaska boundary dispute, and competition in the North Atlantic fisheries.

[37] During the 1912 presidential election, Root was placed in a difficult position regarding his two friends and political partners: William Howard Taft and Theodore Roosevelt.

Beginning in 1910, Roosevelt had begun challenging the absolute authority of judicial review, arguing that the Supreme Court was using its power to strike down necessary reform legislation, as best represented in decisions like Lochner v. New York (1905).

Taft, a lawyer and former judge (and future Supreme Court Chief Justice), was appalled, believing Roosevelt would be a danger to the nation's constitutional order if re-elected.

Root, himself a lawyer and constitutional conservative, agreed with some of Roosevelts criticisms on a personal level, but thought that attacking the court's authority in such an open way was extremely dangerous.

There, he formally counted the delegates that gave the nomination to Taft and offered a speech that aligned the Republican Party with a defense of the Supreme Court's authority.

He was a leading advocate of American entry into the war on the side of the British and French because he feared the militarism of Germany would be bad for the world and for the United States.

The United States never joined, but Root supported the League of Nations and served on the commission of jurists which created the Permanent Court of International Justice.

In 1922, when Root was 77, President Warren G. Harding appointed him as a delegate to the Washington Naval Conference as part of an American team headed by Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes.

Root served as vice president of the American Peace Society, which publishes World Affairs, the oldest U.S. journal on international relations.

During World War II the Liberty ship SS Elihu Root was built in Panama City, Florida, and named in his honor.