Elinor Glyn

Elinor Glyn (née Sutherland; 17 October 1864 – 23 September 1943) was a British novelist and scriptwriter who specialised in romantic fiction, which was considered scandalous for its time, although her works are relatively tame by modern standards.

[1] She was the younger daughter of Douglas Sutherland (1838–1865), a civil engineer of Scottish descent, and his wife Elinor Saunders (1841–1937), of an Anglo-French family that had settled in Canada.

[2][3][a] Her father died when she was two months old; her mother returned to the parental home in Guelph, in what was then Upper Canada, British North America (now Ontario) with her two daughters.

[5][6] Richard's brother Joseph also settled in Upper Canada, publishing one of the first opposition papers there, pursuing liberty, and dying a rebel in 1814.

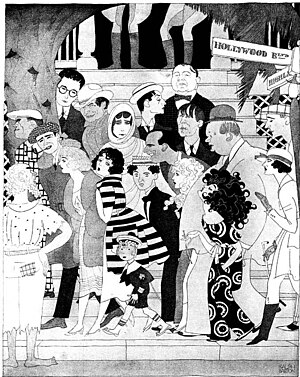

This training not only gave her an entrée into aristocratic circles on her return to Europe, it also led to her reputation as an authority on style and breeding when she worked in Hollywood in the 1920s.

Her novel Three Weeks, about a Balkan queen who seduces a young British aristocrat, was allegedly inspired by her affair with Lord Alistair Innes Ker, brother of the Duke of Roxburghe, sixteen years her junior, which scandalized Edwardian society.

[14][c] In 1915, Curzon leased Montacute House, in South Somerset, for him and Glyn, now a widow as her husband had died that autumn at the age of 58 after several years of illness.

[15] Glyn pioneered risqué, and sometimes erotic, romantic fiction aimed at a female readership, a radical idea for its time.

[1][19] In 1919, she signed a contract with William Randolph Hearst's International Magazine Company to write stories and articles that included a clause for the motion picture rights.

[21] She wrote for Cosmopolitan and other Hearst press titles, advising women on how to keep their men and imparting health and beauty tips.

[23] Apart from being a scriptwriter for the silent movie industry, working for both MGM and Paramount Pictures in Hollywood in the mid-1920s, she had a brief career as one of the earliest female directors.

As her company failed and she exhausted her finances, Glyn decided to retire from film work and instead focus on her first passion, writing novels.

[21] After a short illness, Glyn died on 23 September 1943, at 39 Royal Avenue, Chelsea, London, aged 78,[28] and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium.