Elisha Gray and Alexander Bell telephone controversy

He had begun electrical experiments in Scotland in 1867 and, after emigrating to Boston from Canada, pursued research into a method of telegraphy that could transmit multiple messages over a single wire simultaneously, a so-called "harmonic telegraph".

Bell formed a partnership with two of his students' parents, including prominent Boston lawyer Gardiner Hubbard, to help fund his research in exchange for shares of any future profits.

[3] In the summer of 1874, Gray developed a harmonic telegraph device using vibrating reeds that could transmit musical tones, but not intelligible speech.

After largely abandoning these early experiments, fourteen months later on February 11, 1876, Gray included a diagram for a telephone in his notebook.

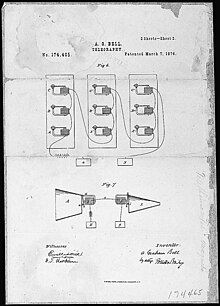

On March 8, Bell recorded an experiment in his lab notebook, with a diagram similar to that of Gray's patent caveat (see right).

[9] In 1879, Bell testified under oath that he discussed "in a general way" Gray's caveat with patent examiner Zenas Fisk Wilber.

In an affidavit from April 8, 1886, Wilber admitted that he was an alcoholic who owed money to his longtime friend and Civil War Army companion Marcellus Bailey, Bell's lawyer.

Only his October 21, 1885 affidavit directly contradicts this story and Wilber claims it was "given at the request of the Bell company by Mr. Swan, of its counsel" and he was "duped to sign it" while drunk and depressed.

"[15] The theory that Alexander Graham Bell stole the idea of the telephone rests on the similarity between drawings of liquid transmitters in his lab notebook of March 1876 to those of Gray's patent caveat of the previous month.

Much of the documentation detailing these experiments includes drawings of liquid transmitters remarkably similar to the design which Bell is alleged to have stolen from Gray in 1876.

Bell had an important advantage over other inventors trying to develop a talking machine: he had been trained in phonetics and had a deep understanding of how human speech is produced by the mouth and how the ear processes sound.

While electricians such as Reis, Gray and Edison used make-or-break currents (like a buzzer) in their attempts, Bell understood acoustics and wave theory and applied this knowledge to analogous work in his electrical experiments.

Melville (who was a friend of George Bernard Shaw and a model for Prof. Henry Higgins in Pygmalion) frequently involved his son Aleck in his work and public demonstrations.

[18] His research into sound production was considered significant enough that Bell was elected into membership in the prestigious London Philological Society at age 19.

[19] He began sending electric currents through tuning forks to transmit sounds through by wire, which he later learned had been anticipated by Helmholtz.

Richards, wrote the inventor a letter at Bell's request describing the experiments and transmission of telegraphic messages over wires using a liquid transmitter filled with mercury.

"You used tuning-forks; and a connection or circuit was made and broken by means of the vibrations of the form (according to its pitch) in a cup containing quicksilver," he recalled.

[22] In 1873, Bell came to realize that his work on the multiple telegraphs could lead to a more important achievement: the transmission of the human voice by electricity.

In October 1873, at his lab at 292 Essex Street in Boston, he began experimenting with vibrating metal strips or "reeds" to transmit speech.

The following quote forms part of the information that is found in the left margin of Bell's patent application, and is alleged by some to have been stolen from Gray's caveat: Though the advisability of using mercury in his device has been questioned, it is Bell's description of how the conducting-wire is immersed (more or less deeply), and the effect on electrical resistance that this does have on the passage of current in "other liquid", that proves his understanding of undulating current and variable resistance in this device, at the time of his patent application.

This is seen in Bell's laboratory notebook entries, where the many drawings of tests that he and Thomas Watson conducted in the days preceding March 10, all show electrode placements similar to those of the eventual working transmitter.

[28] Following his own vision and using the electrode placement described in his patent application, Bell had a working liquid transmitter on the third day of his and Watson's efforts.

According to Evenson, early on Monday, February 14, after learning of the variable resistance feature from Gray's lawyer, Pollok or Bailey inserted the seven sentences into version X, revised the claims, made other minor revisions, and had the clerk prepare a new engrossed fair copy, version G which consists of 14 pages, not including a signature page.

Historian Robert Bruce believed that Wilber, who at the time was near the end of his life, ill, and destitute, was "probably liquored up or bribed, or both.

One week later, Bell built and successfully tested Gray's liquid transmitter which transmitted "Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you" on March 10, 1876.

After March 1876, Bell focused on improving the electromagnetic telephone and never used Gray's liquid transmitter in public demonstrations or commercial use.

[57] When Gray applied for a patent for the variable resistance telephone transmitter, Burton Baker claims that the Patent Office determined "while Gray was undoubtedly the first to conceive of and disclose the [variable resistance] invention, as in his caveat of 14 February 1876, his failure to take any action amounting to completion until others had demonstrated the utility of the invention deprives him of the right to have it considered.

"[58] However, Bell wrote his wife Mabel in March 1901, after several newspaper articles revived the controversy after the death of Gray, that: However, even the Supreme Court Case was mired in corruption.

Chief Justice Morrison Waite's decision regarding the telephone cases was heavily influenced by the fact that the charge of Bell's theft "involves the professional integrity and moral character of eminent attorneys.

In a November 2015 episode[61] of Drunk History, this controversy was reenacted with Martin Starr as Alexander Graham Bell, Henry Winkler as Wilber, and Jason Ritter as Elisha Gray.