Ellen Wilkinson

During the Second World War, Wilkinson served in Churchill's wartime coalition as a junior minister, mainly at the Ministry of Home Security, where she worked under Herbert Morrison.

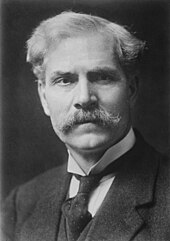

This brought her new contacts, who would typically meet at Fabian summer schools to hear lectures by ILP leaders such as Ramsay MacDonald and Arthur Henderson, and trade union activists such as Ben Tillett and Margaret Bondfield.

[44][45][n 3] "[We] read with incredulous eyes that the Russian people, the workers, the soldiers, and peasants, had really risen and cast out the Tsar and his government ... we did no work at all in the office, we danced around tables and sang ... Everyone with an ounce of liberalism in his composition rejoiced that tyranny had fallen".

[50] She was unsuccessful, but in November 1923 the Gorton ward elected her to Manchester City Council;[3] Hannah Mitchell, her co-worker in prewar suffrage campaigns, was a fellow councillor.

[64] The latter stages of the ensuing general election were dominated by the controversy surrounding the Zinoviev letter, which generated a "Red Scare" shortly before polling day and contributed to a massive Conservative victory.

[76] Wilkinson's ODNB biographer, Brian Harrison, acknowledges that while "women's issues" were often to the fore in her speeches, she was primarily a socialist rather than a feminist, and if forced to decide between them would have chosen the former.

Early in June she joined George Lansbury and other leading Labour and union figures on the platform at an Albert Hall rally which raised around £1,200 for the benefit of the miners, who continued on strike despite the TUC decision.

[6][79] She also visited the United States in August 1926 to raise financial support for the miners, provoking criticism from the Conservative prime minister Baldwin who denied that the lockout was causing hardship.

As a member of Labour's National Executive, Wilkinson helped to draft her party's manifesto, although her preference for a list of specific policy proposals was overruled in favour of a lengthy statement of ideals and objectives.

The Labour Party was divided; the Chancellor, Philip Snowden, favoured a strict curb on public expenditure, while others, including Wilkinson, believed that the problem was not over-production, but under-consumption.

[94][95][n 7] "In a country that calls itself a democracy it really is a scandal that an unelected revising chamber should be tolerated, in which the Conservative Party has a permanent and overwhelming majority" With Wilkinson's assistance, the Mental Treatment Act 1930 received the Royal Assent on 30 June 1930.

[98] As the parliament progressed, it became increasingly difficult to promote social legislation in the face of the mounting financial crisis and the use by the Conservative-dominated House of Lords of its statutory delaying powers.

Early in 1934 Wilkinson led a deputation of Jarrow's unemployed to meet the prime minister, MacDonald, in his nearby Seaham constituency, and received sympathy but no positive action.

[110][n 10] In the November 1935 general election the National Government, led by Baldwin since MacDonald's retirement earlier that year, won convincingly, although Labour increased its House of Commons representation to 158.

[119] Under the general leadership of its chairman, David Riley, the town council began preparations for a demonstration in the form of a march to London to present a petition to the government.

[132][133] The historians Malcolm Pearce and Geoffrey Stewart suggest that the success of the Jarrow march lay in the future; it "helped to shape [post-Second World War] perceptions of the 1930s", and thus paved the way to social reform.

[136] In November 1934, as a representative of the Relief Committee for the Victims of Fascism, Wilkinson visited the northern Spanish province of Asturias to report on the crushing of the Oviedo miners' uprising.

[141] She returned to Spain in April 1937 as a member of an all-women delegation led by the Duchess of Atholl, and afterwards wrote of feeling "a helpless, choking rage", as she witnessed the effects of aerial bombing on undefended villages.

[145][146] In 1937, Wilkinson was one of a group of Labour figures—Aneurin Bevan, Harold Laski and Stafford Cripps were others—who founded the left-wing magazine Tribune; in the first issue she wrote of the need to fight unemployment, poverty, malnutrition and inadequate housing.

In the House of Commons on 6 October 1938 she condemned the actions of the prime minister, Neville Chamberlain,[n 11] in signing the Munich Agreement: "Only by throwing away practically everything for which this country cared and stood could he rescue us from the results of his own policy".

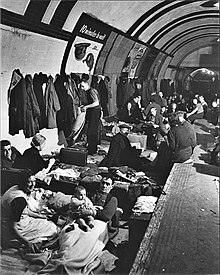

[153] When aerial bombardment of British cities began in the summer of 1940, many Londoners used Underground stations as improvised shelters, often living there for days in conditions of increasing squalor.

[154] By the end of 1941 Wilkinson had supervised the distribution of more than half a million indoor "Morrison shelters"—reinforced steel tables with wire mesh sides, under which a family could sleep at home.

She supported Morrison's decision in January 1941 to suppress the communist newspaper The Daily Worker on the grounds of its anti-British propaganda,[158][159] and voted for the wartime legislation that banned strikes in key industries.

However, many in the Labour Party saw this tripartite arrangement as perpetuating elitism, and wanted a scheme based on "multilateral" schools, or what later became known as the "comprehensive" system; Chuter Ede preferred this, but Attlee had felt it necessary to appoint him as Home Secretary, so he had less influence over education.

[3] Her cautious attitude disappointed and angered some of the Labour left wing and teachers' representatives, who considered that a great opportunity to incorporate socialist principles into education had been missed.

Despite this, speculation that Wilkinson had committed suicide has persisted, the reasons cited being the failure of her personal relationship with Herbert Morrison and her likely fate in a rumoured cabinet reshuffle.

[192] In her later career, ambition and pragmatism led her to temper her earlier Marxism and militancy and work within mainstream Labour Party policy; she came to believe that parliamentary democracy offered a better route to social progress than any alternative.

[196] The historian David Kynaston cites as her greatest practical achievement her success in meeting the timetable for the raising of the school leaving age;[197] her successor as education minister, George Tomlinson, recorded how hard she had fought to avoid postponement of the reform, and expressed his sorrow that she died before the set date.

Vernon says that the relationship almost certainly became "more than platonic", but as Wilkinson's private papers were destroyed after her death, and Morrison maintained silence over the matter, the full nature and extent of their friendship remains uncertain.

[188][202] Labour MP Rachel Reeves noted differing opinions among their respective biographers, but cited a recollection by wartime Minister P. J. Grigg as suggesting a friendship that was more than platonic.