Elliptic curve

An elliptic curve is defined over a field K and describes points in K2, the Cartesian product of K with itself.

If P has degree four and is square-free this equation again describes a plane curve of genus one; however, it has no natural choice of identity element.

More generally, any algebraic curve of genus one, for example the intersection of two quadric surfaces embedded in three-dimensional projective space, is called an elliptic curve, provided that it is equipped with a marked point to act as the identity.

Elliptic curves are especially important in number theory, and constitute a major area of current research; for example, they were used in Andrew Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem.

However, there is a natural representation of real elliptic curves with shape invariant j ≥ 1 as ellipses in the hyperbolic plane

Specifically, the intersections of the Minkowski hyperboloid with quadric surfaces characterized by a certain constant-angle property produce the Steiner ellipses in

described as a locus relative to two foci is uniquely the elliptic curve sum of two Steiner ellipses, obtained by adding the pairs of intersections on each orthogonal trajectory.

that works in both case 1 and case 2 is where equality to yP − yQ/xP − xQ relies on P and Q obeying y2 = x3 + bx + c. For the curve y2 = x3 + ax2 + bx + c (the general form of an elliptic curve with characteristic 3), the formulas are similar, with s = xP2 + xP xQ + xQ2 + axP + axQ + b/yP + yQ and xR = s2 − a − xP − xQ.

For a general cubic curve not in Weierstrass normal form, we can still define a group structure by designating one of its nine inflection points as the identity O.

For example, the equation y2 = x3 + 17 has eight integral solutions with y > 0:[3][4] As another example, Ljunggren's equation, a curve whose Weierstrass form is y2 = x3 − 2x, has only four solutions with y ≥ 0 :[5] Rational points can be constructed by the method of tangents and secants detailed above, starting with a finite number of rational points.

This height function h has the property that h(mP) grows roughly like the square of m. Moreover, only finitely many rational points with height smaller than any constant exist on E. The proof of the theorem is thus a variant of the method of infinite descent[8] and relies on the repeated application of Euclidean divisions on E: let P ∈ E(Q) be a rational point on the curve, writing P as the sum 2P1 + Q1 where Q1 is a fixed representant of P in E(Q)/2E(Q), the height of P1 is about 1/4 of the one of P (more generally, replacing 2 by any m > 1, and 1/4 by 1/m2).

[11] The Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture (BSD) is one of the Millennium problems of the Clay Mathematics Institute.

The conjecture relies on analytic and arithmetic objects defined by the elliptic curve in question.

It is defined as an Euler product, with one factor for every prime number p. For a curve E over Q given by a minimal equation with integral coefficients

, reducing the coefficients modulo p defines an elliptic curve over the finite field Fp (except for a finite number of primes p, where the reduced curve has a singularity and thus fails to be elliptic, in which case E is said to be of bad reduction at p).

The zeta function of an elliptic curve over a finite field Fp is, in some sense, a generating function assembling the information of the number of points of E with values in the finite field extensions Fpn of Fp.

Hasse's conjecture affirms that the L-function admits an analytic continuation to the whole complex plane and satisfies a functional equation relating, for any s, L(E, s) to L(E, 2 − s).

This fact can be understood and proven with the help of some general theory; see local zeta function and étale cohomology for example.

can then be used in the local zeta function as its values when raised to the various powers of n can be said to reasonably approximate the behaviour of

, we can use a reduced zeta function and so which leads directly to the local L-functions The Sato–Tate conjecture is a statement about how the error term

in Hasse's theorem varies with the different primes q, if an elliptic curve E over Q is reduced modulo q.

It was proven (for almost all such curves) in 2006 due to the results of Taylor, Harris and Shepherd-Barron,[19] and says that the error terms are equidistributed.

Elliptic curves over finite fields are notably applied in cryptography and for the factorization of large integers.

If characteristic were not an obstruction, each equation would reduce to the previous ones by a suitable linear change of variables.

In particular, the group E(K) of K-rational points of an elliptic curve E defined over K is finitely generated, which generalizes the Mordell–Weil theorem above.

The properties of the Hasse–Weil zeta function and the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture can also be extended to this more general situation.

The constants g2 and g3, called the modular invariants, are uniquely determined by the lattice, that is, by the structure of the torus.

In particular, the value of the Dedekind eta function η(2i) is Note that the uniformization theorem implies that every compact Riemann surface of genus one can be represented as a torus.

For more see also: Serge Lang, in the introduction to the book cited below, stated that "It is possible to write endlessly on elliptic curves.

The following short list is thus at best a guide to the vast expository literature available on the theoretical, algorithmic, and cryptographic aspects of elliptic curves.

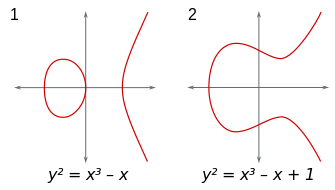

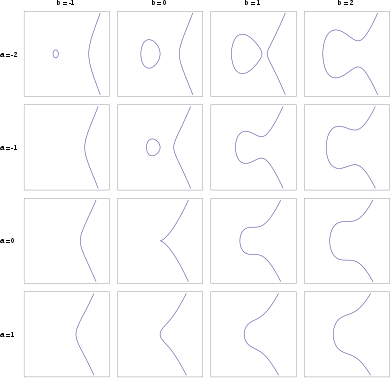

(For ( a , b ) = (0, 0) the function is not smooth and therefore not an elliptic curve.)