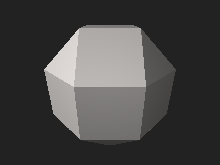

Elongated square gyrobicupola

It is not considered to be an Archimedean solid because it lacks a set of global symmetries that map every vertex to every other vertex, unlike the 13 Archimedean solids.

[2] The elongated square gyrobicupola can be constructed similarly to the rhombicuboctahedron, by attaching two regular square cupolas onto the bases of an octagonal prism, a process known as elongation.

The difference between these two polyhedrons is that one of the two square cupolas is twisted by 45 degrees, a process known as gyration, making the triangular faces staggered vertically.

[3] A convex polyhedron in which all of the faces are regular polygons is a Johnson solid, and the elongated square gyrobicupola is among them, enumerated as the 37th Johnson solid

[4] The elongated square gyrobicupola may have been discovered by Johannes Kepler in his enumeration of the Archimedean solids, but its first clear appearance in print appears to be the work of Duncan Sommerville in 1905.

[5] It was independently rediscovered by J. C. P. Miller in 1930 by mistake while attempting to construct a model of the rhombicuboctahedron.

Its volume can be calculated by slicing it into two square cupolas and one octagonal prism:[3]

The elongated square gyrobicupola possesses three-dimensional symmetry group

It is locally vertex-regular – the arrangement of the four faces incident on any vertex is the same for all vertices; this is unique among the Johnson solids.

[1][7][8] The dihedral angle of an elongated square gyrobicupola can be ascertained in a similar way as the rhombicuboctahedron, by adding the dihedral angle of a square cupola and an octagonal prism:[2] The elongated square gyrobicupola can form a space-filling honeycomb with the regular tetrahedron, cube, and cuboctahedron.

The polyvanadate ion [V18O42]12− has a pseudo-rhombicuboctahedral structure, where each square face acts as the base of a VO5 pyramid.