Empire Theatre (42nd Street)

[6] The theater is part of an entertainment and retail complex at 234 West 42nd Street, which includes the former Liberty Theatre and the Madame Tussauds New York museum.

[1][2] In addition, the Port Authority Bus Terminal is to the west, the New York Times Building is to the south, and the Nederlander Theatre is to the southeast.

[1][2] An entrance to the New York City Subway's Times Square–42nd Street and 42nd Street–Port Authority Bus Terminal stations, served by the 1, 2, 3, 7, <7>, N, Q, R, W, and S trains, is just west of the theater.

[2][10] In the first two decades of the 20th century, eleven venues for legitimate theatre were built within one block of West 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues.

[11][12] The New Amsterdam, Harris, Liberty, Eltinge (now Empire), and Lew Fields theaters occupied the south side of the street.

[17][18] The AMC Empire 25 complex was designed by a joint venture between Benjamin Thompson, Beyer Blinder Belle, Gould Evans Goodman, and the Rockwell Group.

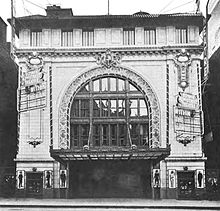

[24][25] According to Christopher Gray of The New York Times, the facade was typical of Lamb's 1910s theater designs, which "emphasized broad swaths of cream- or white-colored glazed terra cotta with a bit of polychromy and deep dramatic piers, window recesses and other large elements".

[28][31] The Eltinge Theatre could not contain interior columns because they would obstruct audience members' sightlines, so the side walls and the ceiling were designed to be stronger and more rigid than in a conventional building.

[17] The sounding board above the proscenium arch contained a mural, which depicted three robed women dancing to music[23][34] and was painted by French artist Arthur Brounet.

[59][61] The next hit at the Eltinge was the play The Yellow Ticket,[61][62] featuring Florence Reed and John Barrymore, which opened in January 1914[63] and ran for 183 performances.

[71][72] Within five years of its opening, the Eltinge Theatre was known as a "lucky house", in part because Woods often booked or produced popular comedies and melodramas.

[77] This was followed by the play Under Orders, which opened in September 1918;[78][79] it ran for several months despite having only two performers, in contrast to many contemporary productions that enjoyed large casts.

[73][85] In July 1921, Samuel Augenblick and Louis B. Brodsky bought the Liberty and Eltinge theaters from the heirs of Charlotte M. Goodridge, although this had no effect on Woods's lease.

[100] In early 1925, the theater hosted Leon Gordon's play The Piker,[101] which was so negatively received that its leading performer, Lionel Barrymore, seldom appeared on Broadway again.

[110] The Lambert Theatre Corporation, a venture in which Bryant was a partner,[111] leased the Eltinge during the 1927–1928 theatrical season, hosting seven shows in eight months.

[115][116] This was followed the next year by Love Honor and Betray with Clark Gable;[117][118] the Theatre Guild's production of A Month in the Country;[119] and the play The Ninth Guest.

[128][129] The Eltinge and the Republic were financially successful by mid-1931,[127] but local business owners opposed burlesque, claiming that the shows encouraged loitering, crime and decreased property values.

[32] After he was elected mayor in 1934, Fiorello La Guardia began a crackdown on burlesque and appointed Paul Moss as license commissioner.

[168] The same year, the City University of New York's Graduate Center hosted an exhibition with photographs of the Empire and other theaters to advocate for the area's restoration.

[180] While the LPC granted landmark status to many Broadway theaters starting in 1987, it deferred decisions on the exterior and interior of the Empire Theatre.

[184] The Urban Development Corporation (UDC), an agency of the New York state government, proposed redeveloping the area around a portion of West 42nd Street in 1981.

[195][196] David Morse and Richard Reinis were selected in April 1982 to develop the mart,[194][195] but they were removed from the project that November due to funding issues.

[201][202] Though the theater was tentatively slated to be used for fashion shows and other events,[202] the city and state governments had not reached an agreement with private developers regarding the mart.

[210] Government officials hoped that the development of the theaters would finally allow the construction of the four towers around 42nd Street, Broadway, and Seventh Avenue.

[212] By 1995, real-estate development firm Forest City Ratner was planning a $150 million entertainment and retail complex on the site of the Empire, Harris, and Liberty theaters.

[217] According to New 42nd Street president Cora Cahan, news articles about the proposed relocation were largely "filled [...] with wonder", in contrast to the mostly negative characterizations of Times Square.

[31][16] Engineers were preparing to raze several buildings along the south side of 42nd Street by mid-1997,[219] including the Lew Fields Theatre, whose site would be occupied by the relocated Empire.

[47] The basements were demolished,[28] allowing the theater building to rest directly on Manhattan's bedrock instead of atop an unstable layer of dirt.

[16][19] After the theater was relocated, Forest City Ratner planned to recreate stonework on the facade, which at several places had been stripped to a layer of brick.

[231] The Empire 25's success was attributed not only to its central location near Times Square but also because it offered independent and art films in addition to major features.