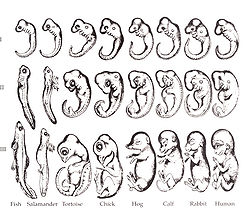

Embryo drawing

The study of comparative embryology aims to prove or disprove that vertebrate embryos of different classes (e.g. mammals vs. fish) follow a similar developmental path due to their common ancestry.

Similarities can be seen along the first two rows; the appearance of specialized characters in each species can be seen in the columns and a diagonal interpretation leads one to Haeckel's idea of recapitulation.

Haeckel's embryo drawings are primarily intended to express his theory of embryonic development, the Biogenetic Law, which in turn assumes (but is not crucial to) the evolutionary concept of common descent.

[3] Ernst Haeckel, along with Karl von Baer and Wilhelm His, are primarily influential in forming the preliminary foundations of 'phylogenetic embryology' based on principles of evolution.

[5] Haeckel proposes that all classes of vertebrates pass through an evolutionarily conserved "phylotypic" stage of development, a period of reduced phenotypic diversity among higher embryos.

Haeckel portrays a concrete demonstration of his Biogenetic Law through his Gastrea theory, in which he argues that the early cup-shaped gastrula stage of development is a universal feature of multi-celled animals.

In addressing his embryo drawings to a general audience, Haeckel does not cite any sources, which gives his opponents the freedom to make assumptions regarding the originality of his work.

Karl E. von Baer and Haeckel both struggled to model one of the most complex problems facing embryologists at the time: the arrangement of general and special characters during development in different species of animals.

Von Baer's scheme of development need not be tied to developmental stages defined by particular characters, where recapitulation involves heterochrony.

During the 19th century, embryologists often obtained early human embryos from abortions and miscarriages, postmortems of pregnant women and collections in anatomical museums.

In response to Haeckel's evolutionary claim that all vertebrates are essentially identical in the first month of embryonic life as proof of common descent, His responds by insisting that a more skilled observer would recognize even sooner that early embryos can be distinguished.

Late 20th and early 21st century critic Stephen Jay Gould[25] has objected to the continued use of Haeckel's embryo drawings in textbooks.

"[27] Haeckel encountered numerous oppositions to his artistic depictions of embryonic development during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

[31] Michael Richardson and his colleagues in a July 1997 issue of Anatomy and Embryology,[32] demonstrated that Haeckel falsified his drawings in order to exaggerate the similarity of the phylotypic stage.

In a March 2000 issue of Natural History, Stephen Jay Gould argued that Haeckel "exaggerated the similarities by idealizations and omissions."

"[35] Some version of Haeckel's drawings can be found in many modern biology textbooks in discussions of the history of embryology, with clarification that these are no longer considered valid.

As well, Haeckel served as a mentor to many important scientists, including Anton Dohrn, Richard and Oscar Hertwig, Wilhelm Roux, and Hans Driesch.

Haeckel then provided a means of pursuing this aim with his biogenetic law, in which he proposed to compare an individual's various stages of development with its ancestral line.

Although Haeckel stressed comparative embryology and Gegenbaur promoted the comparison of adult structures, both believed that the two methods could work in conjunction to produce the goal of evolutionary morphology.

[39] The philologist and anthropologist, Friedrich Müller, used Haeckel's concepts as a source for his ethnological research, involving the systematic comparison of the folklore, beliefs and practices of different societies.

Müller's work relies specifically on theoretical assumptions that are very similar to Haeckel's and reflects the German practice to maintain strong connections between empirical research and the philosophical framework of science.

[42] Modern acceptance of Haeckel's Biogenetic Law, despite current rejection of Haeckelian views, finds support in the certain degree of parallelism between ontogeny and phylogeny.

[43] According to M. S. Fischer, reconsideration of the Biogenetic Law is possible as a result of two fundamental innovations in biology since Haeckel's time: cladistics and developmental genetics.

[46] Although Stephen Jay Gould's 1977 book Ontogeny and Phylogeny helps to reassess Haeckelian embryology, it does not address the controversy over Haeckel's embryo drawings.