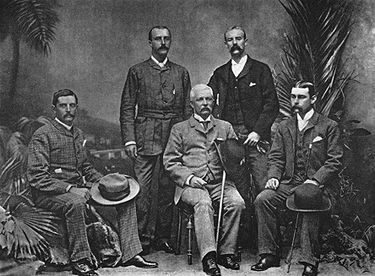

Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

Led by Henry Morton Stanley, its goal was ostensibly the relief of Emin Pasha, the besieged Egyptian governor of Equatoria (part of modern-day South Sudan), who was threatened by Mahdist forces.

Stanley set out to traverse the continent with a force of nearly 700 men, navigating up the Congo River and then through the Ituri rainforest to reach East Africa.

Emin Pasha was a German Jewish-born Ottoman doctor and naturalist who had been appointed Governor of Equatoria by Charles George Gordon, the British general who himself had attempted to relieve Khartoum.

Scottish businessman and philanthropist William Mackinnon had been involved in various colonial ventures, and by November he had approached Stanley about leading a relief expedition.

Emin Pasha may be a good man, a brave officer, a gallant fellow deserving of a strong effort of relief, but I decline to believe, and I have not been able to gather from any one in England an impression, that his life, or the lives of the few hundreds under him, would overbalance the lives of thousands of natives, and the devastation of immense tracts of country which an expedition strictly military would naturally cause.

The expedition is a mere powerful caravan, armed with rifles for the purpose of insuring the safe conduct of the ammunition to Emin Pasha, and for the more certain protection of his people during the retreat home.

But it also has means of purchasing the friendship of tribes and chiefs, of buying food and paying its way liberally.In a number of publications made after the expedition, Stanley asserted that the singular purpose of the effort was to offer relief to Emin Pasha.

These interests were threatened not only by the Mahdists, but also by German imperial ambitions in the region; Germany would not recognize British suzerainty over Zanzibar (and its continental holdings) until 1890.

For eight years, to my knowledge, the matter had been placed before His Highness, but the Sultan's signature was difficult to obtain.The records at the National Archives at Kew, London, offer an even deeper insight and show that annexation was a purpose he had been aware of for the expedition.

Stanley intended to establish a camp on the Aruwimi, then go east overland through unknown territory to reach Lake Albert and Equatoria.

Stanley acted as a representative of Mackinnon in convincing the Sultan of Zanzibar to grant a concession for what later became the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC), and made two agreements with Tippu Tib.

The first included appointing him as Governor of Stanley Falls, an arrangement much criticized in Europe as a deal with a slave-trader, and the second agreement regarded the provisions of carriers for the expedition.

Chartered steamers brought the expedition to Matadi, where the carriers took over, bringing some 800 loads of stores and ammunition to Leopoldville on the Stanley Pool.

The trees of the forest were so tall and dense that little light reached the floor, food was scarcely to be found, and the local Pygmies took the expedition for an Arab raiding party, shooting at them with poisoned arrows.

On 18 April they received a letter from Emin, who had heard about the expedition a year earlier, and had come down the lake in March after hearing rumors of Stanley's arrival.

A month of discussion produced no agreement, and on 24 May Stanley went back to Fort Bodo, arriving there 8 June and meeting Stairs, who had returned from Ugarrowwa's with just fourteen surviving men.

Finally, on 17 August at Banalya, 90 miles upstream from Yambuya, Stanley found Bonny, the sole European left in charge of the column, along with a handful of starving carriers.

Barttelot had been shot in a dispute, Jameson was at Bangala dying of a fever, Troup had been invalided home, and Herbert Ward had gone back down the Congo a second time to telegraph the Relief Committee in London for further instructions (the column had not heard from Stanley in over a year).

But the march soon disintegrated into chaos, with large-scale desertion and multiple trips to try to bring up stores; then on 19 July Barttelot was shot while trying to interfere with a Manyema festival.

[6] In his posthumously published diary, Jameson admitted that he had indeed paid for the girl and watched as she was butchered, but claimed that he considered the whole affair a joke and had not expected her to actually be killed.

I sent my boy for six handkerchiefs, thinking it was all a joke ..., but presently a man appeared, leading a young girl of about ten years old at the hand, and I then witnessed the most horribly sickening sight I am ever likely to see in my life.

The trip to the coast passed first south, along the western flank of the Ruwenzoris, and Stairs attempted to ascend to a summit, reaching 10,677 ft before having to turn around.

At this point they began to learn of the complicated changing situation in East Africa, with European colonial powers scrambling to stake their claims, and a second relief expedition under Frederick John Jackson.

Stanley returned to Europe in May 1890 to tremendous public acclaim; both he and his officers received numerous awards, honorary degrees, and speaking engagements.

By autumn, as the true cost of the expedition became known, and as the families of Barttelot and Jameson reacted to Stanley's accusations of incompetence in the rear column, criticism and condemnation became widespread.

From 1898 to 1900, a devastating sleeping sickness epidemic spread into territories that are now Democratic Republic of the Congo, western Uganda and south of Sudan.

[12] It has been suggested that stories of the expedition — in particular, the disastrous plight of the "rear column" — inspired Joseph Conrad in his 1899 novella Heart of Darkness.

Critic Adam Hochschild suggests that the character of Kurtz, the isolated and insane Congo trader, was modeled on Barttelot, who "went mad, began hitting, whipping, and killing people, and was finally murdered".