Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

[12] Scholarly debates still discuss whether he was truly the last knight (either as an idealized medieval ruler leading people on horseback, or a Don Quixote-type dreamer and misadventurer), or the first Renaissance prince—an amoral Machiavellian politician who carried his family "to the European pinnacle of dynastic power" largely on the back of loans.

Since Hermann Wiesflecker's Kaiser Maximilian I. Das Reich, Österreich und Europa an der Wende zur Neuzeit (1971–1986) became the standard work, a more positive image of the emperor has emerged.

He is seen as a modern, innovative ruler who carried out important reforms and promoted significant cultural achievements, even if the financial costs weighed down the Austrians and his military expansion and caused the deaths and sufferings of many people.

Although the two remained on good terms overall, Frederick was horrified by his only surviving son and heir's overzealousness in chivalric contests, extravagance, and heavy tendencies towards wine, feasts and young women, which became evident during their trips in 1473 and 1474.

The Belgian historian Eugène Duchesne comments that these years were among the saddest and most turbulent in the history of the country, and despite his later great imperial career, Maximilian unfortunately could never compensate for the mistakes he made as regent in this period.

Simpson argue that Maximilian, as a gifted military champion and organizer, did save the Netherlands from France, although the conflict between the Estates and his personal ambitions caused a catastrophic situation in the short term.

[a] Maximilian and his followers had managed to achieve remarkable success in stabilizing the situation though, and a stalemate was kept in Ghent as well as in Bruges, before the tragic death of Mary in 1482 completely turned the political landscape in the whole country upside down.

The brutal efficiency of Germanic mercenaries, together with the financial support of cities outside Flanders like Antwerp, Amsterdam, Mechelen and Brussels as well as a small group of loyal landed nobles proved decisive in the Burgundian-Habsburg regime's final triumph.

Les finances des Pays-Bas bourguignons sous Marie de Bourgogne et Maximilien d'Autriche (1477–1493), Marc Boone comments that the brutality described shows Maximilian and the Habsburg dynasty's insatiable greed of expansion and inability to adapt to local traditions, while Jean-François Lassalmonie opines that the nation building process (successful, with the establishment of a common tax) was remarkably similar to the same process in France, including the hesitation in working with local levels of the political society, except that the struggle was shorter and after 1494 a peaceful dialogue between the prince and the estates was reached.

[65][66][67] After the rebellions, concerning the aristocracy, although Maximilian punished few with death, their properties were largely confiscated and they were replaced with a new elite class loyal to the Habsburgs—among whom, there were noblemen who had been part of traditional high nobility but elevated to supranational importance only in this period.

Maximilian would have liked to see the Guelders matter to be dealt with once and for all, but as Charles later escaped and Philip was at haste to make his 1506 fatal journey to Spain, troubles would soon arise again, leaving Margaret to deal with the problems.

[86] Philip's death in Burgos was a heavy blow personally (Maximilian's entourage seem to have concealed it from him for more than ten days) and also politically, as by this time, he had become his father's most important international ally, although he retained his independent judgement.

After the brutal 1517 campaign of Charles of Egmont in Friesland and Holland, these humanists, in their mistaken belief, spread the stories that the emperor and other princes were concocting clever schemes and creating wars just to expand the Habsburg dominion and extracting money.

[113][114][115] As the Treaty of Senlis had resolved French differences with the Holy Roman Empire, King Louis XII of France had secured borders in the north and turned his attention to Italy, where he made claims to the Duchy of Milan.

Apart from balancing the Reichskammergericht with the Reichshofrat, this act of restructuring seemed to suggest that, as Westphal quoting Ortlieb, the "imperial ruler—independent of the existence of a supreme court—remained the contact person for hard pressed subjects in legal disputes as well, so that a special agency to deal with these matters could appear sensible".

[155] Historian Joachim Whaley points out that there are usually two opposite views on Maximilian's rulership: one side is represented by the works of nineteenth century historians like Heinrich Ullmann or Leopold von Ranke, which criticize him for selfishly exploiting the German nation and putting the interest of his dynasty over his Germanic nation, thus impeding the unification process; the more recent side is represented by Hermann Wiesflecker's biography of 1971–86, which praises him for being "a talented and successful ruler, notable not only for his Realpolitik but also for his cultural activities generally and for his literary and artistic patronage in particular".

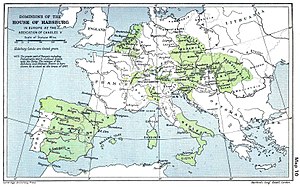

[168][169][170] Stollberg also links the development of the reform to the concentration of supranational power in the Habsburgs' hand, which manifested in the successful dynastic marriages of Maximilian and his descendants (and the successful defense of those lands, notably the rich Low Countries) as well as Maximilian's development of a revolutionary post system that helped the Habsburgs to maintain control of their territories (Additionally, the communication revolution created by the combination of the postal system with printing would boost the empire's capability of disseminating orders and policies as well as its coherence in general, elevating cultural life, and also help reformers like Luther to broadcast their views effectively.).

On the other hand, the attempts he demonstrated in building the imperial system alone shows that he did consider the German lands "a real sphere of government in which aspirations to royal rule were actively and purposefully pursued."

Fichtner states that Maximilian's pan-European vision was very expensive, and his financial practices antagonized his subjects both high and low in Burgundy, Austria and Germany (who tried to temper his ambitions, although they never came to hate the charismatic ruler personally), this was still modest in comparison with what was about to come, and the Ottoman threat gave the Austrians a reason to pay.

From Maximilian's time, as the "terminuses of the first transcontinental post lines" began to shift from Innsbruck to Venice and from Brussels to Antwerp, in these cities, the communication system and the news market started to converge.

Frederick III's cousin and predecessor, Albert II (who was Sigismund's son-in-law and heir through his marriage with Elizabeth of Luxembourg) had managed to combine the crowns of Germany, Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia under his rule, but he died young.

The successful expansion (with the notable role of marriage policy) under Maximilian bolstered his position in the Empire, and also created more pressure for an imperial reform, so that they could get more resources and coordinated help from the German territories to defend their realms and counter hostile powers such as France.

[299] Maximilian was strongly built, had an upright posture, was over six feet tall, had blue eyes, neck length blond or reddish hair, a large hooked nose and a jutting jaw (like his father, he always shaved his beard.

[316] In his mature years, he exerted restraint on personal habits, except during his depressive phases (when he drank night and day, sometimes incapacitating the government, to the great annoyance of Chancellor Zyprian von Sernteiner) or in the companion of his artist friends.

The artists got preferential treatment in criminal matters too, such as the case of Veit Stoss, whose sentence (imprisonment and having his hands chopped off for an actual crime) issued by Nuremberg got cancelled on the sole basis of genius.

[318][319] Historian Ernst Bock, with whom Benecke shares the same sentiment, writes the following about him:[320] His rosy optimism and utilitarianism, his totally naive amorality in matters political, both unscrupulous and machiavellian; his sensuous and earthy naturalness, his exceptional receptiveness towards anything beautiful especially in the visual arts, but also towards the various fashions of his time whether the nationalism in politics, the humanism in literature and philosophy or in matters of economics and capitalism; further his surprising yearning for personal fame combined with a striving for popularity, above all the clear consciousness of a developed individuality: these properties Maximilian displayed again and again.Historian Paula Fichtner describes Maximilian as a leader who was ambitious and imaginative to a fault, with self-publicizing tendencies as well as territorial and administrative ambitions that betrayed a nature both "soaring and recognizably modern", while dismissing Benecke's presentation of Maximilian as "an insensitive agent of exploitation" as influenced by the author's personal political leaning.

[323] On the other hand, Steven Beller criticizes him for being too much of a medieval knight who had a hectic schedule of warring, always crisscrossing the whole continent to do battles (for example, in August 1513, he commanded Henry VIII's English army in the second Guinegate, and a few weeks later joined the Spanish forces in defeating the Venetians) with little resources to support his ambitions.

[324] Thomas A. Brady Jr. praises the emperor's sense of honour, but criticizes his financial immorality—according to Geoffrey Parker, both points, together with Maximilian's martial qualities and hard-working nature, would be inherited from the grandfather by Charles V:[209][325] [...]though punctilious to a fault about his honor, he lacked all morals about money.

Every florin was spent, mortgaged, and promised ten times over before it ever came in; he set his courtiers a model for their infamous venality; he sometimes had to leave his queen behind as pledge for his debts; and he borrowed continuously from his servitors—large sums from top officials, tiny ones from servants—and never repaid them.

[326] According to Wiesflecker, people could often depend on his promises more than those of most princes of his days, although he was no stranger to the "clausola francese" and also tended to use a wide variety of statements to cover his true intentions, which unjustly earned him the reputation of being fickle.