Encyclopédie

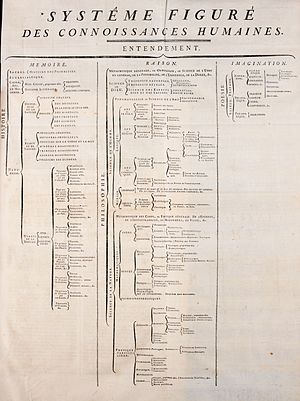

[4] Diderot wanted to incorporate all of the world's knowledge into the Encyclopédie and hoped that the text could disseminate all this information to the public and future generations.

This four page prospectus was illustrated by Jean-Michel Papillon,[13] and accompanied by a plan, stating that the work would be published in five volumes from June 1746 until the end of 1748.

The Journal reported that Mills had discussed the work with several academics, was zealous about the project, had devoted his fortune to support this enterprise, and was the sole owner of the publishing privilege.

Among those hired by Malves were the young Étienne Bonnot de Condillac, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and Denis Diderot.

[23] Because of its occasional radical contents, the Encyclopédie caused much controversy in conservative circles, and after the publication of the second volume, it was briefly suspended from publishing by royal edict of 1752.

Joly de Fleury accused it of "destroying royal authority, fomenting a spirit of Independence and revolt, and...laying the foundations of an edifice of error, for the corruption of morals and religion, and the promotion of unbelief.

[26] Despite these issues, work continued "in secret," partially because the project had highly placed supporters, such as Malesherbes and Madame de Pompadour.

[27] The authorities deliberately ignored the continued work; they thought their official ban was sufficient to appease the church and other enemies of the project.

Since the objective of the editors of the Encyclopédie was to gather all the knowledge in the world, Diderot and D'Alembert knew they would need various contributors to help them with their project.

Instead they were a disparate group of men of letters, physicians, scientists, craftsmen and scholars ... even the small minority who were persecuted for writing articles belittling what they viewed as unreasonable customs—thus weakening the might of the Catholic Church and undermining that of the monarchy—did not envision that their ideas would encourage a revolution.Following is a list of notable contributors with their area of contribution (for a more detailed list, see Encyclopédistes): Due to the controversial nature of some of the articles, several of its editors were sent to jail.

[31] Like most encyclopedias, the Encyclopédie attempted to collect and summarize human knowledge in a variety of fields and topics, ranging from philosophy to theology to science and the arts.

[35] The writers further doubted the authenticity of presupposed historical events cited in the Bible and questioned the validity of miracles, such as the Resurrection.

[36] However, some contemporary scholars argue the skeptical view of miracles in the Encyclopédie may be interpreted in terms of "Protestant debates about the cessation of the charismata.

The Encyclopédie and its contributors endured many attacks and attempts at censorship by the clergy or other censors, which threatened the publication of the project as well as the authors themselves.

A playwright, Charles Palissot de Montenoy, wrote a play called Les Philosophes to criticize the Encyclopédie.

[39] When Abbé André Morellet, one of the contributors to the Encyclopédie, wrote a mock preface for it, he was sent to the Bastille due to allegations of libel.

[41] Nonetheless, the contributors still openly attacked the Catholic Church in certain articles with examples including criticizing excess festivals, monasteries, and celibacy of the clergy.

This Enlightenment ideal, espoused by Rousseau and others, advocated that people have the right to consent to their government in a form of social contract.

To balance the desires of individuals and the needs of the general will, humanity requires civil society and laws that benefit all persons.

[45] At the same time, the Encyclopédie was a vast compendium of knowledge, notably on the technologies of the period, describing the traditional craft tools and processes.

These articles applied a scientific approach to understanding the mechanical and production processes, and offered new ways to improve machines to make them more efficient.

In The Encyclopédie and the Age of Revolution, a work published in conjunction with a 1989 exhibition of the Encyclopédie at the University of California, Los Angeles, Clorinda Donato writes the following: The encyclopedians successfully argued and marketed their belief in the potential of reason and unified knowledge to empower human will and thus helped to shape the social issues that the French Revolution would address.

[48] Given that Paris was the intellectual capital of Europe at the time and that many European leaders used French as their administrative language, these ideas had the capacity to spread.

As do Wikipedians today, Diderot and his colleagues needed to engage with the latest technology in dealing with the problems of designing an up-to-date encyclopedia.