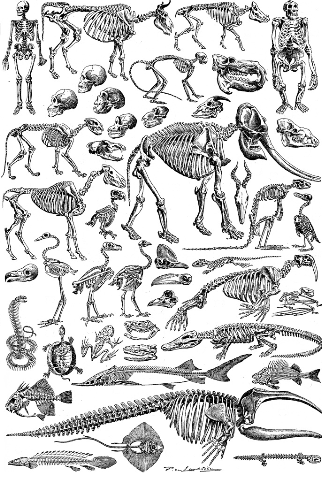

Endoskeleton

[1][2] Endoskeletons serve as structural support against gravity and mechanical loads, and provide anchoring attachment sites for skeletal muscles to transmit force and allow movements and locomotion.

Being more centralized in structure also means more compact volume, making it easier for the circulatory system to perfuse and oxygenate, as well as higher tissue density against stress.

An endoskeleton may function purely for structural support (as in the case of Porifera), but often also serves as an attachment site for muscles and a mechanism for transmitting muscular forces as in chordates and echinoderms, which provides a means of locomotion.

In the more basal subphylum Cephalochordata (lancelets), the endoskeleton consists of solely of an elastic glycoprotein-collagen rod called notochord, which stores energy like a spring and enable more energy-efficient swimming.

The soft connective tissues of sponges are composed of gelatinous mesohyl reinforced by fibrous spongin, forming a composite matrix that has decent tensile strength but severely lacks the rigidity needed to resist deformation from ocean currents.