Energy policy of Canada

"[34] During the 2019 federal election campaign, both the Liberals and Conservatives had "agreed to try to hit existing Paris commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent by 2030.

"[35] The Canada research chair in climate and energy policy, Nicholas Rivers, said that there is not enough discussion of "renewable technologies such as wind power, solar and zero-emissions aluminum" in the electricity sector.

The producing provinces impose royalties and taxes on oil and natural gas production; provide drilling incentives; and grant permits and licenses to construct and operate facilities.

[45] According to the 2 May 2019 International Monetary Fund (IMF) report, in 2015, Canada paid US$43 billion in post-tax energy subsidies which represents 2.9 percent of the GDP and an expenditure of US$1,191 per capita.

[10]: 35 On the eve of the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) held in Paris, CBC news reported that G20 countries spend US$452 billion annually on fossil fuel subsidies.

A recent SWOT analysis conducted in 2013 of a Canadian energy and climate policies has shown that there is a lack of consistency between federal and regional strategies.

[8] In 2015, the federal government worked with Canada's provincial leaders and reached an agreement for cooperating in boosting the nation's industry while transitioning to a low-carbon economy.

However, the vast majority of those reserves are located hundreds or thousands of kilometres from the country's industrial centres and seaports, and the effect of high transportation costs is that they remain largely unexploited.

At the same time, the Western provinces export their coal to 20 different countries, particularly Japan, Korea, and China, in addition to using it in their own thermal power plants.

The region between New Brunswick and Saskatchewan, a distance of thousands of kilometres which includes the major industrial centres of Ontario and Quebec, is largely devoid of coal.

In contrast, oil production in the United States grew rapidly in the first part of the 20th century after huge discoveries were made in Texas, Oklahoma, California and elsewhere.

The situation changed dramatically in 1947 when Imperial Oil drilled into a peculiar anomaly on its newly developed seismic recordings near the then-village of Leduc, Alberta.

Many people questioned why it was built to an American port rather than a Canadian one, but the federal government was more interested in the fact that oil exports completely erased the country's trade deficit.

A year later, the Gordon Commission's nationalist flavour found practical expression with the creation of the Canada Development Corporation, to "buy back" Canadian industries and resources with deals that included a takeover of the Western operations of France's Aquitaine and their conversion into Canterra Energy.

The wave of direct action spread to Alberta when Premier Peter Lougheed and his Conservatives won power in 1971, ending 36 years of Social Credit rule.

Lougheed's elaborate election platform, titled New Directions, sounded themes common among OPEC countries by pledging to create provincial resources and oil growth companies, collect a greater share of energy revenues, and foster economic diversification to prepare for the day when petroleum reserves ran out.

The idea of limited resources emerged from the realm of theory into hard facts of policy when the NEB rejected natural-gas export applications in 1970 and 1971, on grounds that there was no surplus and Canada needed the supplies.

The strength of the new conservationist sentiment was underlined when the NEB held its position despite a 1971 declaration by the federal Department of Energy that it thought Canada had a 392-year supply of natural gas and enough oil for 923 years.

Alberta premier Peter Lougheed soon announced that his government would revise its royalty policy in favour of a system linked to international oil prices.

Since the federal government based its spending on the larger figure, the result was that it spent a great deal of money on subsidies that could not be recovered in taxes on production.

None of these transactions was illegal, or even unusual considering the integrated nature of the economies, but all had the effect of transferring billions of Canadian tax dollars to the balance sheets of (mostly foreign owned) companies.

Production costs are considerably higher than in the Middle East, but this is offset by the fact that the geological and political risks are much lower than in most major oil-producing areas.

In the late 1940s, Alberta's Conservation Board addressed wasteful production practices, and the Dinning Commission supported prioritizing Albertans for gas supplies.

The federal government, aligning with Alberta's approach, treated natural gas as a Canadian resource, regulating exports through the Pipe Lines Act in 1949.

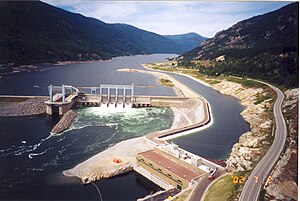

[71] Although the new Site C dam is expected to have a large initial electricity surplus, the former Liberal government of the province proposed to sell this power rather than using it to cut the 65 million m3 (2.3 billion cu ft) per day of natural gas consumption.

In 1926 it signed long-term contracts to buy electricity from power companies in Quebec, but these proved controversial when jurisdictional disputes impeded development of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers and the Great Depression reduced demand.

However, hydroelectric capacity in Ontario was inadequate to meet growing demand, so coal burning power stations were built near Toronto and Windsor in the early 1950s.

The Quebec government followed the example of Ontario in nationalizing its electrical sector, and in 1944 expropriated the assets of the monopoly Montreal Light, Heat and Power Company to create a new crown corporation called Hydro-Québec.

In 1945, the provincial government created a crown corporation, the BC Power Commission (BCPC), to acquire small utilities and extended electrification to rural and isolated areas.

[83] On 23 October 1891 a group of entrepreneurs obtain a 10-year permit to build the Edmonton Electric Lighting and Power Company on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River.