Engine balance

For example, if the weights of pistons or connecting rods are different between cylinders, the reciprocating motion can cause vertical forces.

If the shaft cannot be designed such that its resonant frequency is outside the projected operating range, e.g. for reasons of weight or cost, it must be fitted with a damper.

Vibration occurs around the axis of a crankshaft, since the connecting rods are usually located at different distances from the resistive torque (e.g. the clutch).

This particularly affects straight and V-engines with a 180° or single-plane crankshaft in which pistons in neighbouring cylinders simultaneously pass through opposite dead centre positions.

In a car, for example, such an engine with cylinders larger than about 500 cc/30 cuin[citation needed] (depending on a variety of factors) requires balance shafts to eliminate undesirable vibration.

These measurements show the need for various balancing methods as well as other design features to reduce vibration amplitudes and damage to the locomotive itself as well as to the rails and bridges.

The example locomotive is a simple, non-compound, type with two outside cylinders and valve gear, coupled driving wheels and a separate tender.

The first two motions are caused by the reciprocating masses and the last two by the oblique action of the con-rods, or piston thrust, on the guide bars.

The resilience of the track in terms of the weight of the rail as well as the stiffness of the roadbed can affect the vibration behaviour of the locomotive.

The part of the main rod assigned a revolving motion was originally measured by weighing it supported at each end.

The horizontal motions for unbalanced locomotives were quantified by M. Le Chatelier in France, around 1850, by suspending them on ropes from the roof of a building.

They were run up to equivalent road speeds of up to 40 MPH and the horizontal motion was traced out by a pencil, mounted on the buffer beam.

The shape could be enclosed in a 5⁄8-inch square for one of the unbalanced locomotives and was reduced to a point when weights were added to counter revolving and reciprocating masses.

They may not be a reliable indicator of a requirement for better balance as unrelated factors may cause rough riding, such as stuck wedges, fouled equalizers and slack between the engine and tender.

Also the position of an out-of-balance axle relative to the locomotive centre of gravity may determine the extent of motion at the cab.

[16] In the United States it is known as dynamic augment, a vertical force caused by a designer's attempt to balance reciprocating parts by incorporating counterbalance in wheels.

[18] Up until about 1923 American locomotives were balanced for static conditions only with as much as 20,000 lb variation in main axle load above and below the mean per revolution from the unbalanced couple.

A different source of varying wheel/rail load, piston thrust, is sometimes incorrectly referred to as hammer blow or dynamic augment although it does not appear in the standard definitions of those terms.

As an alternative to adding weights to driving wheels the tender could be attached using a tight coupling that would increase the effective mass and wheelbase of the locomotive.

The Prussian State Railways built two-cylinder engines with no reciprocating balance but with a rigid tender coupling.

[26] With the locomotive's static weight known the amount of overbalance which may be put into each wheel to partially balance the reciprocating parts is calculated.

Excessive hammer blow from high slipping speeds was a cause of kinked rails with new North American 4–6–4s and 4–8–4s that followed the 1934 A.A.R.

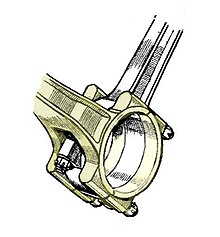

[30] The steam engine cross-head sliding surface provides the reaction to the connecting rod force on the crank-pin and varies between zero and a maximum twice during each revolution of the crankshaft.

In a double-acting steam engine, as used in a railway locomotive, the direction of the vertical thrust on the slide bar is always upwards when running forward.

[33] The tendency of the variable force on the upper slide is to lift the machine off its lead springs at half-stroke, and ease it down at the ends of stroke.