English Benedictine Reform

The artistic workshops established by Æthelwold reached a high standard of craftsmanship in manuscript illustration, sculpture and gold and silver, and were influential both in England and on the Continent.

In his monasteries, learning reached a high standard, producing competent prose and poetry in the elaborate hermeneutic style of Latin favoured in tenth-century England.

His Winchester school played an important role in creating the standard vernacular West Saxon literary language, and his pupil Ælfric was its most eminent writer.

[1] The seventh century saw the development of a powerful monastic movement in England, which was strongly influenced by the ideas of St Benedict, and the late seventh-century English scholar Aldhelm assumed that monasteries would normally follow the Benedictine Rule.

[3] Political and financial pressures, partly due to disruption caused by Viking attacks, led to an increasing preference for pastoral clergy, who provided essential religious services to the laity, over contemplative monks.

[12] When Gérard of Brogne reformed the Abbey of Saint Bertin in Saint-Omer along Benedictine lines in 944, dissident monks found a refuge in England under King Edmund (939–946).

[16] Modest religious and diplomatic contacts between England and the Continent under Alfred and his son Edward the Elder (899–924) intensified during the reign of Æthelstan, which saw the start of the monastic revival.

[18] Dunstan and Æthelwold reached maturity in Æthelstan's cosmopolitan, intellectual court in the 930s, where they met monks from the European reformed houses which provided the inspiration for the English movement.

The reformers' propaganda, mainly from Æthelwold's circle, claimed that the church was transformed in Edgar's reign, but in Blair's view the religious culture "when we probe beneath the surface, starts to look less exclusive and more like that of Æthelstan's and Edmund's".

[38] The reformers aimed to enhance the Christian character of kingship, and one aspect of this was to raise the status of the queen; Edgar's last wife, Ælfthryth, was the first king's consort to regularly witness charters as regina.

[43] Nobles made donations to reformed foundations for religious reasons, and many believed that they could save their souls by patronising holy men who would pray for them, and thus help to expiate their sins.

The historian Janet Pope comments: "It appears that religion, even monasticism, could not break the tight kin group as the basic social structure in tenth-century England.

"[51] Æthelwold reformed monasteries in his own diocese of Winchester, and he also helped to restore houses in eastern England, such as Peterborough, Ely, Thorney and St Neots.

After 980 he made several attempts to gain the patronage of leading English churchmen, but they were unsuccessful, probably because monastic reformers were unwilling to assist a secular canon living abroad.

[63] Reformers attached great importance to the elevation and translation of saints, moving their bodies from their initial resting place to a higher and more prominent location to make them more accessible for veneration.

Between around 600 and 800 the location and orientation of roads, buildings and property boundaries on a number of elite sites respected planning grids, including the early seventh century royal centre at Yeavering, where a Roman surveying instrument called a groma has been found.

All the lay noblemen of the time had cause for alarm at the great increase in wealth and power enjoyed by the reformed monasteries in the 960s and 970s and the sometimes dubious means they employed to acquire land.

[81] No spiritual leaders of the church emerged in the eleventh century comparable with the three main figures of the monastic reform, and the position of monks in English religious and political life declined.

[84] Keynes says: The principal motivation or driving force behind the re-establishment of religious houses in the kingdom of the English, living in strict accordance with the Rule of Saint Benedict, was a desire to restore to their former glory some of the ancient houses known from the pages of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People, from other literary works, from historical traditions of the later eighth and ninth centuries, or indeed from the physical remains of buildings ... Modern historians will recognise how much was owed to the monastic reform movements on the continent, and will find extra dimensions, such as a wish to extend royal influence into areas where a king of the West Saxon line might not expect his writ to run, or a more general wish to revive a sense of 'Englishness', through raising awareness of the traditions of the past.

[85] Antonia Gransden sees some continuity of the Anglo-Saxon monastic tradition from its origin in seventh-century Northumbria, and argues that historians have exaggerated both the importance of the tenth-century reform and its debt to Continental models.

It was the emergence of small local churches and the development of new systems of pastoral care – processes only imperfectly documented – that would have the more enduring impact and more thoroughgoing effect on religious life in England.

[89][d] In the view of Catherine Cubitt the reform "has rightly been regarded as one of the most significant episodes in Anglo-Saxon history", which "transformed English religious life, regenerated artistic and intellectual activities and forged a new relationship between church and king".

These developments were underpinned by the mutual attachment of the reformed church and the crown, the melding of continental influence with insular continuity and a stronger focus on individual piety and salvation.

[93] Helmut Gneuss observes that although the reformed monasteries were confined to the south and midlands, "here a new golden age of monastic life in England dawned and brought in its train a renaissance of culture, literature and art".

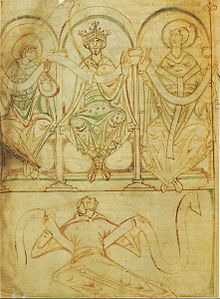

The Benedictional of St Æthelwold (Winchester, probably 970s, now British Library) is recognised as the most important of a group of surviving illuminated manuscripts, lavishly illustrated with extravagant acanthus leaf borders.

[101] According to Barbara Yorke, "The artistic workshops established at Æthelwold's foundations during his lifetime were to continue as influential schools of craftsmen after his death, and had a widespread influence both in England and on the Continent.

[107] The skilled use of line drawing continued to be a feature of English art for centuries, for example in the Eadwine Psalter (Canterbury, probably 1150s) and the work of Matthew Paris, monk of St Albans (c. 1200 – 1259) and his followers.

[109] Generally the contemporary sources give much more detail on the valuable treasures in precious metal, rich embroidered cloth, and other materials which the monasteries were able to accumulate, largely from gifts by the elite.

[114] Ælfric, who is described by Claudio Leonardi as "the highest pinnacle of Benedictine reform and Anglo-Saxon literature",[115] shared in the movement's monastic ideals and devotion to learning, as well as its close relations with leading lay people.

In 2005 John Blair commented: "Ecclesiastical historians' distaste for the lifestyle of secular minsters, which has become less explicit but can even now seem virtually instinctive, reflects contemporary partisanship absorbed into a historiographical tradition which has privileged the centre over the localities, and the ideals of the reformers over the realities and needs of grass-roots religious life."