English Electric Lightning

Overwing fuel tank fittings were installed in the F6 variant and gave an extended range, but limited maximum speed to a reported 1,000 miles per hour (1,600 km/h).

In 1947, Petter approached the Ministry of Supply (MoS) with his proposal, and in response Specification ER.103 was issued for a single research aircraft, which was to be capable of flight at Mach 1.5 (1,593 km/h; 990 mph) and 50,000 ft (15,000 m).

[citation needed] On 29 March 1949 the MoS granted approval to start a detailed design, develop wind tunnel models and build a full-size mockup.

[15] The Royal Aircraft Establishment disagreed with Petter's choice of sweep angle (60 degrees) and tailplane position (low) considering it to be dangerous.

[19] The prototypes were powered by un-reheated Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire turbojets, as the selected Rolls-Royce Avon engines had fallen behind schedule due to their own development problems.

[21] Outwardly, the prototypes looked very much like the production series, but they were distinguished by the rounded-triangular air intake with no centre-body at the nose, short fin, and lack of operational equipment.

A faster version, the "thin-wing Javelin", would offer limited supersonic performance and make it marginally useful against the Tu-22, while a new missile, "Red Dean" would allow head-on attacks.

In March 1957, Duncan Sandys released the 1957 Defence White Paper which outlined the changing strategic environment due to the introduction of ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads.

Although missiles of the era had relatively low accuracy compared to a manned bomber, any loss of effectiveness could be addressed by the ever-increasing yield of the warhead.

This suggested that there was no targeting of the UK that could not be carried out by missiles, and Sandys felt it was unlikely that the Soviets would use bombers as their primary method of attack beyond the mid-to-late 1960s.

To further improve its capability, in July 1957 the Blue Vesta program was reactivated in a slightly simplified form, allowing head-on attacks against an aircraft whose fuselage was heated through skin friction while flying supersonically.

While the P.1B was potentially faster than the FD2, it lacked the fuel capacity to provide one run in each direction at maximum speed to claim the record in accordance with international rules.

[34] The event was celebrated in traditional style in a hangar at RAE Farnborough, with the prototype XA847 having the name 'Lightning' freshly painted on the nose in front of the RAF Roundel, which almost covered it.

To best perform this intercept mission, emphasis was placed on rate-of-climb, acceleration, and speed, rather than range – originally a radius of operation of 150 miles (240 km) from the V bomber airfields was specified – and endurance.

It is likely that the VG Lightning would have adopted a solid nose (by moving the air inlet to the sides or to upper fuselage) to install a larger, more capable radar.

[39] On later variants of the Lightning, a ventral weapons pack could be installed to equip the aircraft alternatively with different armaments, including missiles, rockets, and cannons.

[64] Early versions of the Lightning were equipped with the Ferranti-developed AI.23 monopulse radar, which was contained right at the front of the fuselage within an inlet cone at the centre of the engine intake.

[70] Unlike the previous generation of aircraft which used gaseous oxygen for lifesupport, the Lightning employed liquid oxygen-based apparatus for the pilot; cockpit pressurisation and conditioning was maintained through tappings from the engine compressors.

[76][78] An alternative to the modernisation of existing aircraft would have been the development of more advanced variants; a proposed variable-sweep wing Lightning would have likely involved the adoption of a new powerplant and radar and was believed by BAC to significantly increase performance, but ultimately was not pursued.

[83][page needed] In 1984, during a NATO exercise, Flight lieutenant Mike Hale intercepted a U-2 at a height which they had previously considered safe (thought to be 66,000 feet (20,000 m)).

The shock cone was eventually weakened due to the fatigue caused by the thermal cycles involved in regularly performing high-speed flights.

[99][100] The production Lightning F.1 entered service with the AFDS in May 1960, allowing the unit to take part in the air defence exercise "Yeoman" later that month.

[103] In addition to its training and operational roles, 74 Squadron was appointed as the official Fighter Command aerobatic team for 1961, flying at air shows throughout the United Kingdom and Europe.

[99] The Lightning F.1 would only be ordered in limited numbers and serve for a short time; nonetheless, it was viewed as a significant step forward in Britain's air defence capabilities.

The transfer of McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom IIs from Royal Navy service enabled these much longer-ranged aircraft to be added to the RAF's interceptor force alongside those withdrawn from Germany as they were replaced by SEPECAT Jaguars in the ground attack role.

In their final years the airframes required considerable maintenance to keep them airworthy due to the sheer number of accumulated flight hours.

[125][126] Saudi Arabia received Northrop F-5E fighters from 1971, which resulted in the Lightnings relinquishing the ground-attack mission, concentrating on air defence, and to a lesser extent, reconnaissance.

[130][131] In 1985 as part of the agreement to sell the Panavia Tornado to the RSAF, the 22 flyable Lightnings were traded in to British Aerospace and returned to Warton in January 1986.

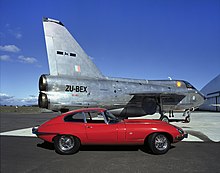

[125][132] Thunder City, a private company based at Cape Town International Airport, South Africa operated one Lightning T.5 and two single-seat F.6es.

[136] The Silver Falcons, the South African Air Force's official aerobatic team, flew a missing man formation after it was announced that the pilot had died in the crash.