English Poor Laws

[12] An attempt to rein in prices, the ordinance (and subsequent acts, such the Statute of Labourers of 1351) required that everyone who could work did; that wages were kept at pre-plague levels; and that food was not overpriced.

[18] In 1530, during the reign of Henry VIII, a proclamation was issued, describing idleness as the "mother and root of all vices"[19] and ordering that whipping should replace the stocks as the punishment for vagabonds.

In 1535, a bill was drawn up calling for the creation of a system of public works to deal with the problem of unemployment, to be funded by a tax on income and capital.

The Vagabonds Act 1547 was passed that subjected vagrants to some of the more extreme provisions of the criminal law, namely two years servitude and branding with a "V" as the penalty for the first offence, and death for the second.

[28] Those who "of his or their forward willful mind shall obstinately refuse to give weekly to the relief of the poor according to his or their abilities" could be bound over to justices of the peace and fined £10.

[29] Additionally, the 1572 Act further enabled Justices of the Peace to survey and register the impotent poor, determine how much money was required for their relief, and then assess parish residents weekly for the appropriate amount.

[31] In the early 1580s, with the development of English colonisation schemes, initially in Ireland and later in North America, a new method to alleviate the condition of the poor would be suggested and utilised considerably over time.

[32] At the same time Richard Hakluyt, in his preface to Divers Voyages, likens English planters to "Bees...led out by their Captaines to swarme abroad"; he recommends "deducting" the poor out of the realm.

[33] By 1619 Virginia's system of indentured service would be fully developed, and subsequent colonies would adopt the method with modifications suitable to their different conditions and times.

Historian George Boyer has stated that England suffered rapid inflation at this time caused by population growth, the debasement of coinage and the inflow of American silver.

[2] Poor harvests in the period between 1595 and 1598 caused the numbers in poverty to increase, while charitable giving had decreased after the dissolution of the monasteries and religious guilds.

The system provided social stability yet by 1750 needed to be adapted to cope with population increases,[46] greater mobility and regional price variations.

The society published several pamphlets on the subject, and supported Sir Edward Knatchbull in his successful efforts to steer the Workhouse Test Act through Parliament in 1723.

The demands, needs and expectations of the poor also ensured that workhouses came to take on the character of general social policy institutions, combining the functions of creche, and night shelter, geriatric ward and orphanage.

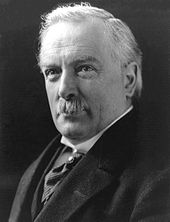

Following peace in 1814, the Tory government of Lord Liverpool[54] passed the Corn Laws[55] to keep the price of grain artificially high.

3. c. 34), "to authorise the issue of Exchequer Bills and the Advance of Money out of the Consolidated Fund, to a limited Amount, for the carrying on of Public Works and Fisheries in the United Kingdom and Employment of the Poor in Great Britain".

[58] Boyer suggests several possible reasons for the gradual increase in relief given to able-bodied males, including the enclosure movement and a decline in industries such as wool spinning and lace making.

[64] The royal commission's primary concerns were with illegitimacy (or "bastardy"), reflecting the influence of Malthusians, and the fear that the practices of the Old Poor Law were undermining the position of the independent labourer.

The Poor Law Commission set up by Earl Grey took a year to write its report, the recommendations passed easily through Parliament support by both main parties the Whigs and the Tories.

Less eligibility was in some cases impossible without starving paupers, and the high cost of building workhouses incurred by rate payers meant that outdoor relief continued to be a popular alternative.

These measures ranged from the introduction of prison-style uniforms to the segregation of inmates into separate yards for men, women, boys, and girls.

In 1886 the Chamberlain Circular encouraged the Local Government Board to set up work projects when unemployment rates were high rather than use workhouses.

The welfare reforms of the Liberal government[92] made several provisions to provide social services without the stigma of the Poor Law, including old age pensions and National Insurance, and from that period fewer people were covered by the system.

[96][97][98] Numbers using the Poor Law system increased during the interwar years and between 1921 and 1938 despite the extension of unemployment insurance to virtually all workers except the self-employed.

The Unemployment Assistance Board was set up in 1934 to deal with those not covered by the earlier National Insurance Act 1911 passed by the Liberals, and by 1937 the able-bodied poor had been absorbed into this scheme.

[103] In 1948 the Poor Law system was finally abolished with the introduction of the modern welfare state and the passing of the National Assistance Act.

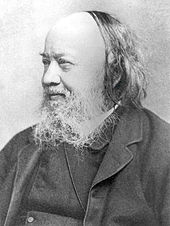

[105] Jeremy Bentham argued for a disciplinary, punitive approach to social problems, whilst the writings of Thomas Malthus focused attention on overpopulation, and the growth of illegitimacy.

Some who gave evidence to the Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws suggested that the existing system had proved adequate and was more adaptable to local needs.

Poor Law commissioners faced greatest opposition in Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire where in 1837 there was high unemployment during an economic depression.

[125] Blaug argues that Old Poor Law was a device "for dealing with the problems of structural unemployment and substandard wages in the lagging rural sector of a rapidly growing but still underdeveloped economy".