English cannon

[2] According to the contemporary poet Jean Froissart, the English cannon made "two or three discharges on the Genoese", which is taken to mean individual shots by two or three guns because of the time taken to reload such primitive artillery.

[2] Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the development of cannon made revolutionary changes to siege warfare throughout Europe, with many castles becoming susceptible to artillery fire.

In England, significant changes were evident from the 16th century, when Henry VIII began building Device Forts between 1539 and 1540 as artillery fortresses to counter the threat of invasion from France and Spain.

One of the first ships to be able to fire a full cannon broadside was the English carrack the Mary Rose, built in Portsmouth from 1510–1512, and equipped with 78 guns (91 after an upgrade in the 1530s).

Many merchant vessels were armed with cannon and the aggressive activities of English privateers, who engaged the galleons of the Spanish treasure fleets, helped provoke the first Anglo-Spanish War, though it was not one of the main factors.

[7] A fleet review on Elizabeth I's accession in 1559 showed the navy to consist of 39 ships and in 1588, Philip II of Spain launched the Spanish Armada against England.

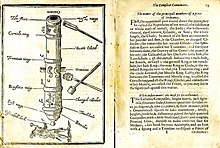

A description of the Gunner's art is given during the English Civil War period (mid-17th century) by John Roberts, covering the modes of calculation and the ordnance pieces themselves, in his work The Compleat Cannoniere, printed London 1652 by W. Wilson and sold by George Hurlock (Thames Street).

The lower tier of English ships of the line at this time were usually equipped with demi-cannon – a naval gun which fired a 32-pound solid shot.

[10] When Quebec was finally captured during the French and Indian War, the British had more cannon installed in the fortifications, and built more embrasures into the walls to maximise their effectiveness against siege batteries.

However, British cannon proved effective, as a heavy cannonade on the French batteries allowed them to hold out long enough for reinforcements.

In January 1793, two troops of Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) were raised to provide fire support for the cavalry, joined by two more in November 1793.

[10] Additionally, the carronade was adopted by the Royal Navy in 1779, and the lower muzzle velocity of the round shot was intended to create many more of the deadly wooden splinters when hitting the structure of an enemy vessel; these in fact were often the main cause of casualties.

The carronade was initially very successful and widely adopted, although in the 1810s and 1820s, greater emphasis was placed on the accuracy of long-range gunfire, and less on the weight of a broadside.

The carronade disappeared from the Royal Navy from the 1850s after the development of steel, jacketed cannon by William George Armstrong and Joseph Whitworth.

[14] During the Napoleonic Wars, a British gun team consisted of 5 numbered gunners – fewer crew than needed in the previous century.

The No.2 was the "spongeman" who cleaned the bore with the sponge dampened with water between shots; the intention being to quench any remaining embers before a fresh charge was introduced.