Enheduanna

2300 BC) was the entu (high) priestess of the moon god Nanna (Sīn) in the Sumerian city-state of Ur in the reign of her father, Sargon of Akkad (r. c. 2334 – c. 2279 BCE).

However, there is considerable debate among modern Assyriologists based on linguistic and archaeological grounds as to whether or not she actually wrote or composed any of the rediscovered works that have been attributed to her.

Her existence was first rediscovered by modern archaeology in 1927, when Sir Leonard Wooley excavated the Giparu in the ancient city of Ur and found an alabaster disk with her name, association with Sargon of Akkad, and occupation inscribed on the reverse.

Enheduanna's archaeological rediscovery has attracted a considerable amount of attention and scholarly debate in modern times related to her potential attribution as the first known named author.

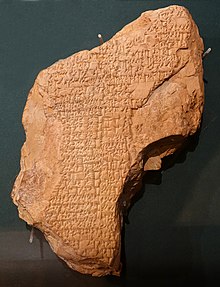

[citation needed] In 1927, as part of excavations at Ur, British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley discovered an alabaster disk shattered into several pieces, which has since been reconstructed.

The front side shows the high priestess standing in worship as what has been interpreted as a nude male figure pours a libation.

[10] Irene Winter states that "given the placement and attention to detail" of the central figure, "she has been identified as Enheduanna"[11] Two seals bearing her name, belonging to her servants and dating to the Sargonic period, have been excavated at the Giparu at Ur.

[13] Black et al. suggest that "perhaps Enheduanna has survived in scribal literature" due to the "continuing fascination with the dynasty of her father Sargon of Akkad".

Falkenstein suggested that this might be evidence of Enheduanna's authorship, but acknowledged that the hymns are only known from the later Old Babylonian period and that more work would need to be done constructing and analyzing the received texts before any conclusions could be made.

Probably composed in exile in Ĝirsu, the song is intended to persuade the goddess Inanna to intervene in the conflict in favor of Enheduanna and the Sargonian dynasty.

Inanna has thus become the mistress of heaven and earth alike – and thus empowered to enforce her will even over the originally superior gods (An and Nanna), which results in the destruction of Ur and Lugal-Ane.

[26] Also called The Great-Hearted Mistress or The Stout-Hearted Mistress (incipit in-nin ša-gur-ra), the Hymn to Inanna, which is only partially preserved in a fragmentary form, is outlined by Black et al. as containing three parts: an introductory section (lines 1–90) emphasizing Inanna's "martial abilities"; a long, middle section (lines 91–218) that serves as a direct address to Inanna, listing her many positive and negative powers, and asserting her superiority over other deities, and a concluding section (219–274) narrated by Enheduanna that exists in a very fragmentary form.

[29] Black et al. describe these lands as "home to the nomadic, barbarian tribes who loom large in Sumerian literature as forces of destruction and chaos" that sometimes need to be "brought under divine control".

Hallo, responding to Miguel Civil, not only still maintains[33] Enheduanna's authorship of all of the works attributed to her, but rejects "excess skepticism" in Assyriology as a whole, and noting that "rather than limit the inferences they draw from it" other scholars should consider that "the abundant textual documentation from Mesopotamia... provides a precious resource for tracing the origins and evolution of countless facets of civilization.

"[34] Summarizing the debate, Paul A. Delnero, professor of Assyriology at Johns Hopkins University, remarks that "the attribution is exceptional, and against the practice of anonymous authorship during the period; it almost certainly served to invest these compositions with an even greater authority and importance than they would have had otherwise, rather than to document historical reality".

In a BBC Radio 4 interview, Assyriologist Eleanor Robson credits this to the feminist movement of the 1970s, when, two years after attending a lecture by Cyrus H. Gordon in 1976, American anthropologist Marta Weigle introduced Enheduanna to an audience of feminist scholars as "the first known author in world literature" with her introductory essay "Women as Verbal Artists: Reclaiming the Sisters of Enheduanna".

[37] Rather than as a "pioneer poetess" of feminism,[37] Robson states that the picture of Enheduanna from the surviving works of the 18th century BCE is instead one of her as "her father's political and religious instrument".