Washington Doctrine of Unstable Alliances

Interstate rivalries, violent insurrections such as the Whiskey Rebellion, solidifying opposition to the federal government in the form of the Anti-Federalist Party, and the US dependence on trade with Europe weakened the new nation.

[1] Receiving counsel from Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, who cautioned the president that "we forget how little we can annoy," Washington became convinced that the United States could not further antagonize the Kingdom of Great Britain and feared the possibility of British-imposed commercial isolation, which would precipitate an economic catastrophe that would "overturn the constitution and put into an overwhelming majority the anti-national forces.

"[2] At the same time, radical government elements, led by Thomas Jefferson, had all but declared their support for American aid to the beleaguered French First Republic, which was at war with Great Britain.

"[3] In his valedictory Farewell Address, Washington announced his decision to step down from the presidency, partly because of his increasing weariness with public life, and included a short passage defending his policy of ignoring French requests for American assistance.

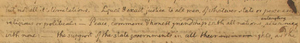

[2][4][5] In an attempt to keep his remarks apolitical, Washington defended his policy by framing it as generic guidance for the future and avoided mentioning the French by name:[2] The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign nations, is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible.

He believed that US commercial power would allow it to pursue an independent course, unfettered by conventional diplomacy,[8] and he wrote to a protégé: The day is within my time as well as yours, when we may say by what laws other nations treat us on the sea.

[9] Although some argue interpret Washington's advice to apply in the short term, until the geopolitical situation had stabilized, the doctrine has endured as a central argument for American non-interventionism.