Enthalpy

[1] It is a state function in thermodynamics used in many measurements in chemical, biological, and physical systems at a constant external pressure, which is conveniently provided by the large ambient atmosphere.

As a state function, enthalpy depends only on the final configuration of internal energy, pressure, and volume, not on the path taken to achieve it.

The total enthalpy of a system cannot be measured directly because the internal energy contains components that are unknown, not easily accessible, or are not of interest for the thermodynamic problem at hand.

In practice, a change in enthalpy is the preferred expression for measurements at constant pressure, because it simplifies the description of energy transfer.

When transfer of matter into or out of the system is also prevented and no electrical or mechanical (stirring shaft or lift pumping) work is done, at constant pressure the enthalpy change equals the energy exchanged with the environment by heat.

Enthalpies of chemical substances are usually listed for 1 bar (100 kPa) pressure as a standard state.

The enthalpy of an ideal gas is independent of its pressure or volume, and depends only on its temperature, which correlates to its thermal energy.

Real gases at common temperatures and pressures often closely approximate this behavior, which simplifies practical thermodynamic design and analysis.

[6][7] The enthalpy H of a thermodynamic system is defined as the sum of its internal energy and the product of its pressure and volume:[1]

The enthalpy of a closed homogeneous system is its energy function H( S, p ) , with its entropy S[ p ] and its pressure p as natural state variables which provide a differential relation for dH of the simplest form, derived as follows.

Here Cp is the heat capacity at constant pressure and α is the coefficient of (cubic) thermal expansion:

[note 1] In a more general form, the first law describes the internal energy with additional terms involving the chemical potential and the number of particles of various types.

For example, when a virtual parcel of atmospheric air moves to a different altitude, the pressure surrounding it changes, and the process is often so rapid that there is too little time for heat transfer.

For example, H and p can be controlled by allowing heat transfer, and by varying only the external pressure on the piston that sets the volume of the system.

Cases of long range electromagnetic interaction require further state variables in their formulation, and are not considered here.

Energy must be supplied to remove particles from the surroundings to make space for the creation of the system, assuming that the pressure p remains constant; this is the p V term.

However, for most chemical reactions, the work term p ΔV is much smaller than the internal energy change ΔU, which is approximately equal to ΔH.

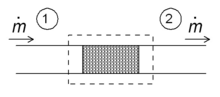

The region of space enclosed by the boundaries of the open system is usually called a control volume, and it may or may not correspond to physical walls.

The definition of enthalpy, H, permits us to use this thermodynamic potential to account for both internal energy and p V work in fluids for open systems:

Note that the previous expression holds true only if the kinetic energy flow rate is conserved between system inlet and outlet.

During steady-state operation of a device (see turbine, pump, and engine), the average d U /d t may be set equal to zero.

This yields a useful expression for the average power generation for these devices in the absence of chemical reactions:

The technical importance of the enthalpy is directly related to its presence in the first law for open systems, as formulated above.

It gives the melting curve and saturated liquid and vapor values together with isobars and isenthalps.

With numbers: This means that the mass fraction of the liquid in the liquid–gas mixture that leaves the throttling valve is 64%.

The term enthalpy was coined relatively late in the history of thermodynamics, in the early 20th century.

Energy was introduced in a modern sense by Thomas Young in 1802, while entropy by Rudolf Clausius in 1865.

[note 3] Introduction of the concept of "heat content" H is associated with Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron and Rudolf Clausius (Clausius–Clapeyron relation, 1850).

[28] It is attributed to Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who most likely introduced it orally the year before, at the first meeting of the Institute of Refrigeration in Paris.

The definition of H as strictly limited to enthalpy or "heat content at constant pressure" was formally proposed by A. W. Porter in 1922.