Eos

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Eos (/ˈiːɒs/; Ionic and Homeric Greek Ἠώς Ēṓs, Attic Ἕως Héōs, "dawn", pronounced [ɛːɔ̌ːs] or [héɔːs]; Aeolic Αὔως Aúōs, Doric Ἀώς Āṓs)[1] is the goddess and personification of the dawn, who rose each morning from her home at the edge of the river Oceanus to deliver light and disperse the night.

In Greek tradition and poetry, she is characterized as a goddess with a great sexual appetite, who took numerous human lovers for her own satisfaction and bore them several children.

Like her Roman counterpart Aurora and Rigvedic Ushas, Eos continues the name of an earlier Indo-European dawn goddess, Hausos.

In surviving tradition, Aphrodite is the culprit behind Eos' numerous love affairs, having cursed the goddess with insatiable lust for mortal men.

In Greek literature, Eos is presented as a daughter of the Titans Hyperion and Theia, the sister of the sun god Helios and the moon goddess Selene.

In another story, she carried off the Athenian Cephalus against his will, but eventually let him go for he ardently wished to be returned to his wife, though not before she denigrated her to him, leading to the couple parting ways.

[11] Heinrich Wilhelm Stoll offered a different (now rejected) etymology for ἠὼς, linking it to the verb αὔω, meaning "to blow", "to breathe.

[13] Karl Kerenyi observes that Tito shares a linguistic origin with Eos's lover Tithonus, which belonged to an older, pre-Greek language.

[14] All four of the aforementioned goddesses sharing a linguistic connection with Eos are considered derivatives of the Proto-Indo-European stem *h₂ewsṓs (later *Ausṓs), "dawn".

Rather, a commonly occurring epithet of hers is δῖα, dîa, meaning "divine", from earlier *díw-ya, which would have translated into "belonging to Zeus" or "heavenly".

[47] Even though the two goddesses are still connected as sisters in the traditions going with lineage from Pallas, their brother Helios is never included with them in those versions, being consistently the son of Hyperion.

[59] From the Iliad: Now when Dawn in robe of saffron was hastening from the streams of Oceanus, to bring light to mortals and immortals, Thetis reached the ships with the armor that the god had given her.

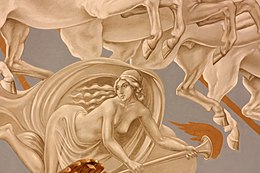

Quintus described her exulting in her heart over the radiant horses (Lampus and Phaëton) that drew her chariot, amidst the bright-haired Horae, the feminine Hours, the daughters of Zeus and Themis who are responsible for the changing of the seasons, climbing the arc of heaven and scattering sparks of fire.

The myth goes that Eos fell in love with and abducted Tithonus, a handsome prince from Troy, either the brother or the son of King Laomedon (the father of Priam).

So for a while the two lived happily in her palace, but their happiness eventually came to an end when Tithonus’ hair started turning grey as he aged, and Eos ceased to visit him in their bed.

Despite that, the goddess kept him around and nourished him with food and ambrosia; Tithonus never died as he had gained immortality as Zeus promised, but he kept aging and shrivelling, and was soon unable to even move.

[79][80] In the account of Hieronymus of Rhodes from the third century BC, the blame is shifted from Eos and onto Tithonus, who asked for immortality but not agelessness from his lover, who was then unable to help him otherwise and turned him into a cicada.

[81] Propertius wrote that Eos did not forsake Tithonus, old and aged as he was, and would still embrace him and hold him in her arms rather than leaving him deserted in his cold chamber, while cursing the gods for his cruel fate.

Cephalus, troubled by her words, asked Eos to change his form into that of a stranger's, in order to secretly put Procris's love for him to the test.

This time however it was Procris's turn to doubt her husband's fidelity; while hunting, he would often call upon the breeze ('Aura' in Latin, sounding similar to Eos's Roman equivalent Aurora) to refresh his body.

[89] The second-century CE traveller Pausanias knew of the story of Cephalus's abduction too, though he calls Eos by the name of Hemera, goddess of day.

[91] Antoninus Liberalis also largely follows the same tradition in his rendition of the myth, though his text contains a lacuna, jumping from Eos' abduction of Cephalus to him having doubts over Procris.

[98] She is joined in fight against the Giants by her siblings, her mother Theia, and possibly, conjectured due to the disembodied wing to the right of Eos's shoulder, the goddess Hemera.

Much like Thetis, the mother of Achilles, did before her, Eos asked the smithing god Hephaestus with tears in her eyes to forge an armor for Memnon, and he, moved, did as told.

[104] Eos was imagined as a woman wearing a saffron mantle as she spread dew from an upturned urn, or with a torch in hand, riding a chariot.

[105] Greek and Italian vases show Eos/Aurora on a chariot preceding Helios, as the morning star Eosphorus flies with her; she is winged, wearing a fine pleated tunic and mantle.

[107] Because Hermes' rod had the power to both induce sleep to mortals and wake them up, some times he is seen preceding the chariot of Eos (and that of Helios) as the new day breaks.

[109] Perhaps the earliest representation of this theme is found on a red-figure rhyton, a statuette-vase, from circa 480-470 BC in which Eos is depicted carrying of a naked boy, perhaps Cephalus, her wings spread and her feet barely touching the ground.

[110] The image of Zeus, the active erastes, pursuing Ganymede, the passive eromenos, was also common, but in the case of Eos, the female figure was put in the dominant position.

Although distinct deities in early works such as Hesiod's Theogony, later the tragic poets completely identified Eos with Hemera, the primordial goddess of the day;[58][113] each of the three great Athenian tragedians, Euripides, Aeschylus and Sophocles, used "Hemera" for the goddess who abducts Tithonus or drives a chariot drawn by white horses at daybreak in some work.