Epaminondas

Accordingly, in later centuries the Roman orator Cicero called him "the first man of Greece", and in more recent times Michel de Montaigne judged him one of the three "worthiest and most excellent men" who had ever lived.

The changes Epaminondas wrought on the Greek political order did not long outlive him, as the cycle of shifting hegemonies and alliances continued unabated.

[8] What has been recorded of Epaminondas's immediate family is that his father was called Polymnis, he had a brother named Caphisias, and both parents lived to see his victory at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC.

He learned how to handle a cither, to play the flute, and to dance, and, while exercising in the gymnasium (traditionally a cornerstone of Theban education), he demonstrated a preference for agility over sheer strength.

[9] Lysis had a significant influence on Epaminondas, who grew devoted to his aged teacher, embraced his Pythagorean philosophy, and later reportedly took special care of his grave.

The ancient sources also draw attention to his skill in military matters and eloquence, as well as his taciturn demeanor, steadfast wit, and aptitude for crude humor.

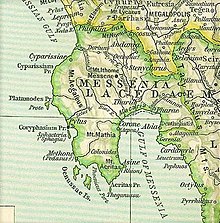

[12][13] Thebes, meanwhile, had greatly increased its own power during the war and sought to gain control of the other cities of Boeotia (the region of ancient Greece northwest of Attica).

[14] In 382 BC, however, the Spartan commander Phoebidas committed an act that would ultimately turn Thebes against Sparta for good and pave the way for Epaminondas's rise to power.

Epaminondas supposedly served in a Theban contingent that aided Sparta in its attack against the city of Mantinea in 385 BC, during which he is said to have saved the life of Pelopidas, an act that cemented their friendship.

They then assassinated the leaders of the pro-Spartan government, and supported by Epaminondas and Gorgidas, who led a group of young men, and a force of Athenian hoplites, they surrounded the Spartans on the Cadmeia.

At first, the Thebans feared facing the Spartans head on, but the conflict gave them much practice and training, and they "had their spirits roused and their bodies thoroughly inured to hardships, and gained experience and courage from their constant struggles".

[24][25][26] Immediately following the failure of the peace talks, orders were sent out from Sparta to the Spartan king Cleombrotus, who was at the head of an army in Phocis, commanding him to march directly to Boeotia.

Most importantly, since it constituted a significant proportion of the entire Spartan manpower, 400 of the 700 Spartiates present were killed, a loss that posed a serious threat to Sparta's future war-making abilities.

[54][52] Epaminondas' campaign of 370/369 BC has been described as an example of "the grand strategy of indirect approach", which was aimed at severing "the economic roots of her [Sparta's] military supremacy.

In order to accomplish all that he wished in the Peloponnesus, Epaminondas had persuaded his fellow Boeotarchs to remain in the field for several months after their term of office had expired.

According to Cornelius Nepos, in his defense Epaminondas merely requested that, if he be executed, the inscription regarding the verdict read:[55] Epaminondas was punished by the Thebans with death, because he obliged them to overthrow the Lacedaemonians at Leuctra, whom, before he was general, none of the Boeotians durst look upon in the field, and because he not only, by one battle, rescued Thebes from destruction, but also secured liberty for all Greece, and brought the power of both people to such a condition, that the Thebans attacked Sparta, and the Lacedaemonians were content if they could save their lives; nor did he cease to prosecute the war, till, after settling Messene, he shut up Sparta with a close siege.

Epaminondas' acceptance of the Achaean oligarchies roused protests by both the Arcadians and his political rivals, and his settlement was thus shortly reversed: democracies were set up, and the oligarchs exiled.

[72] Realising that the time allotted for the campaign was drawing to a close, and reasoning that if he departed without defeating the enemies of Tegea, Theban influence in the Peloponnesus would be destroyed, he decided to stake everything on a pitched battle.

In the clash of infantry, the issue briefly hung in the balance, but then the Theban left-wing broke through the Spartan line, and the entire enemy phalanx was put to flight.

Plutarch also mentions two of his beloveds (eromenoi): Asopichus, who fought together with him at the battle of Leuctra, where he greatly distinguished himself;[82] and Caphisodorus, who fell with Epaminondas at Mantineia and was buried by his side.

Still earlier than these, in the times of the Medes and Persians, there were Solon, Themistocles, Miltiades, and Cimon, Myronides, and Pericles and certain others in Athens, and in Sicily Gelon, son of Deinomenes, and still others.

His innovative strategy at Leuctra allowed him to defeat the vaunted Spartan phalanx with a smaller force, and his decision to refuse his right flank was the first recorded instance of such a tactic.

With Epaminondas removed from the scene, the Thebans returned to their more traditional defensive policy, and within a few years, Athens had replaced them at the pinnacle of the Greek political system.

[90] Finally, at Chaeronea in 338 BC, the combined forces of Thebes and Athens, driven into each other's arms for a desperate last stand against Philip of Macedon, were crushingly defeated, and Theban independence was put to an end.

A mere 27 years after the death of the man who had made it preeminent throughout Greece, Thebes was wiped from the face of the Earth, its 1,000-year history ended in the space of a few days.

Cicero eulogized him as "the first man, in my judgement, of Greece,"[91] and Pausanias records an honorary poem from his tomb:[92] By my counsels was Sparta shorn of her glory, And holy Messene received at last her children.

Those same Spartans, however, had been at the center of resistance to the Persian invasions of the 5th century BC, and their absence was sorely felt at Chaeronea; the endless warfare in which Epaminondas played a central role weakened the cities of Greece until they could no longer hold their own against their neighbors to the north.

Simon Hornblower asserts that Thebes' great legacy to fourth century and Hellenistic Greece was federalism, "a kind of alternative to imperialism, a way of achieving unity without force", which "embodies a representative principle".

[93] For all his noble qualities, Epaminondas was unable to transcend the Greek city-state system, with its endemic rivalry and warfare, and thus left Greece more war-ravaged but no less divided than he found it.

Hornblower asserts that "it is a sign of Epaminondas' political failure, even before the battle of Mantinea, that his Peloponnesian allies fought to reject Sparta rather than because of the positive attractions of Thebes".