Epstein–Barr virus

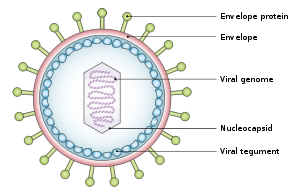

[19][23][24] The virus is about 122–180 nm in diameter and is composed of a double helix of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) which contains about 172,000 base pairs encoding 85 genes.

This "first complete atomic model [includes] the icosahedral capsid, the capsid-associated tegument complex (CATC) and the dodecameric portal—the viral genome translocation apparatus.

[25] Human CD35, also known as complement receptor 1 (CR1), is an additional attachment factor for gp350 / 220, and can provide a route for entry of EBV into CD21-negative cells, including immature B-cells.

[25] Early lytic gene products have many more functions, such as replication, metabolism, and blockade of antigen processing.

[25] Finally, late lytic gene products tend to be proteins with structural roles, such as VCA, which forms the viral capsid.

[25] EGCG, a polyphenol in green tea, has shown in a study to inhibit EBV spontaneous lytic infection at the DNA, gene transcription, and protein levels in a time- and dose-dependent manner; the expression of EBV lytic genes Zta, Rta, and early antigen complex EA-D (induced by Rta), however, the highly stable EBNA-1 gene found across all stages of EBV infection is unaffected.

[33] Additionally, the activation of some genes but not others is being studied to determine just how to induce immune destruction of latently infected B cells by use of either TPA or sodium butyrate.

[19][24] Epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation and cellular chromatin constituents, suppress the majority of the viral genes in latently infected cells.

[25] EBV infection of B lymphocytes leads to "immortalization" of these cells, meaning that the virus causes them to continue dividing indefinitely.

Normally, cells have a limited lifespan and eventually die, but when EBV infects B lymphocytes, it alters their behavior, making them "immortal" in the sense that they can keep dividing and surviving much longer than usual.

Eventually, when host immunity develops, the virus persists by turning off most (or possibly all) of its genes and only occasionally reactivates and produces progeny virions.

The manipulation of the human body's epigenetics by EBV can alter the genome of the cell to leave oncogenic phenotypes.

[49] All EBV nuclear proteins are produced by alternative splicing of a transcript starting at either the Cp or Wp promoters at the left end of the genome (in the conventional nomenclature).

The initiation codon of the EBNA-LP coding region is created by an alternate splice of the nuclear protein transcript.

[50] Clinically, the most common way to detect the presence of EBV is enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay (ELISA).

[65] Specifically, EBV infected B cells have been shown to reside within the brain lesions of multiple sclerosis patients,[17] and a 2022 study of 10 million soldiers' historical blood samples showed that "Individuals who were not infected with the Epstein–Barr virus virtually never get multiple sclerosis.

[66] Additional diseases that have been linked to EBV include Gianotti–Crosti syndrome, erythema multiforme, acute genital ulcers, and oral hairy leukoplakia.

[71] The Epstein–Barr virus has been implicated in disorders related to alpha-synuclein aggregation (e.g. Parkinson's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy).

[73] While the cause and exact mechanism for this is unknown, the byproduct results in errors and breakage of the chromosomal structure as cells stemming from the line of the tainted genome undergo mitosis.

Research involving tissue samples from individuals with various conditions revealed that viral sequences were highly conserved, indicating long-term persistence from dominant strains.

This integration likely occurred via microhomology-mediated end joining, suggesting a potential mechanism through which EBV may influence tumorigenesis.

Moreover, instances of high viral loads and accompanying genetic diversity were noted in patients with active disease, underscoring the virus's dynamic nature within the host and its possible contribution to the progression of EBV-associated cancers.

[75][76] In 1961, Epstein, a pathologist and expert electron microscopist, attended a lecture on "The commonest children's cancer in tropical Africa—a hitherto unrecognised syndrome" by D. P. Burkitt, a surgeon practicing in Uganda, in which Burkitt described the "endemic variant" (pediatric form) of the disease that now bears his name.

Virus particles were identified in the cultured cells, and the results were published in The Lancet in 1964 by Epstein, Achong, and Barr.

[76][77] Cell lines were sent to Werner and Gertrude Henle at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia who developed serological markers.

Laboratories around the world continue to study the virus and develop new ways to treat the diseases it causes.

Although many viruses are assumed to have this property during infection of their natural hosts, there is not an easily managed system for studying this part of the viral lifecycle.

Genomic studies of EBV have been able to explore lytic reactivation and regulation of the latent viral episome.

[12][13] The absence of effective animal models is an obstacle to development of prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines against EBV.

[46] Antiviral agents act by inhibiting viral DNA replication, but there is little evidence that they are effective against Epstein–Barr virus.