Equine intelligence

The discovery of the Clever Hans effect, followed by the development of ethological studies, has progressively revealed a high level of social intelligence evident in horse's behavior.

The horse has played an important socio-economic role across various historical periods, serving humans in labor, combat, sports, therapy, consumption, and religious practices.

[S 8][S 9] He recognized situational intelligence in warhorses of Athens[S 10] and strongly advocated against using violence in training: What a horse does by force it does not learn, and that cannot be beautiful, any more than if one wanted to make a man dance with a whip and a goad: ill-treatment will never produce anything but clumsiness and bad grace.A significant portion of medieval technical literature consists of treatises on veterinary care.

[S 20] In 1868, the Spanish writer Carlos Frontaura observed the "great intelligence" (gran inteligencia) of the horses pulling Parisian omnibuses, praising their initiative.

[S 21] According to Jocelyne Porcher, 19th- and 20th-century zootechnicians applied the "animal machine" hypothesis to horses, drawing on the ideas of René Descartes, Nicolas Malebranche, and Francis Bacon.

[S 18] Social pressures discouraged researchers from challenging these views, as their findings might not be well received, given that the "animal machine" concept was easier to defend in the context of industrialized farming practices.

[H 5][H 6][12][S 21] This black horse, raised in Germany, became an international sensation in the early 20th century due to his supposed ability to solve complex arithmetic problems by tapping his hoof to indicate answers:[13][14][S 1] Crowds flock daily to the inner courtyard of Griebenow Street in northern Berlin, where his master puts him to work, to witness the extraordinary performance of the one who would henceforth be known as "Clever Hans".Belgian philosopher Vinciane Despret notes the prolonged scientific debate sparked by Hans’s abilities, questioning whether horses possess conceptual intelligence.

[16] German psychologist Oskar Pfungst later revealed that Hans was not actually calculating but was instead highly attuned to human body language, stopping his hoof taps when he detected subtle cues.

[20] Ethologist Léa Lansade emphasizes that, at the time and up until the 1960s, animals were considered "intelligent" only if they demonstrated human-like abilities—such as calculating or learning sign language—even though these skills were not necessarily aligned with their natural behaviors.

[22] Early research in equine ethology began with Pearl Gardner in the 1930s,[23] where horses were initially tested under controlled conditions commonly used for laboratory animals, using mechanisms that granted access to food.

[27] Modern interpretations of intelligence focus on the ability to solve problems,[26][S 23] establish relationships between elements, and assimilate new information, rather than merely demonstrating good memory.

[28] To navigate these definitional challenges, some researchers, including Michel-Antoine Leblanc[S 42] and Léa Lansade,[29] focus on describing horses' cognitive processes without attempting to quantify their intellectual performance.

[30][S 43] Horses, as herbivorous prey animals, exhibit cognition and behavior that present different scientific questions compared to carnivorous domestic species like dogs and cats.

[S 38][S 40][31] Beyond suppressing their innate flight responses in frightening situations, horses are trained to communicate and cooperate with humans, a species they might naturally associate with predators.

[40] Leblanc also points out that expressions of intelligence can vary greatly within the same individual and species,[25] depending on factors such as social preferences or the ability to engage in abstract thinking.

[S 92] Ethnologist María Fernanda de Torres Álvarez suggests that working relationships may allow horses to apply their cognitive abilities to solve practical problems.

The learning performance of horses in maze tests has been found to be similar to that of other species, including tropical fish, octopuses, and guinea pigs, in some studies.

[S 102] In 2009, a study by Evelyn Hanggi and Jerry Hingersol provided the first scientific evidence of long-term memory in horses, showing that they could retain complex memories—such as learning rules and performing mental tasks—for up to ten years.

[66] Based on practical experiences, Doctor of Theatre Studies Charlène Dray suggests that show horses are capable of improvising on stage without expecting a reward, provided they have exploratory objects available.

[99] This type of learning is particularly important for foals or adult horses placed in a new environment, as it helps them adjust to noises, human touch, and the sight of unusual objects.

[101] PhD in animal behavior biology Evelyn B. Hanggi and sociologist Vanina Deneux-Le Barh emphasize the persistence of beliefs that attribute limited abilities to horses.

[S 163] Leblanc cites the example of many riders who "deny any intelligence in the horse" while simultaneously attributing complex mental processes to it, using anthropomorphic phrases such as "he did it on purpose to annoy me.

[105] Equestrian journalist Maria Franchini also reported in 2009 hearing frequent claims about horses' low intellectual capacities, both in stables and in major media outlets.

[S 164] In an appearance on the show La Tête au carré on October 3, 2007, geneticist Axel Kahn asserted that horses possess much more limited intellectual capacities than octopuses, primates, and cetaceans.

[S 165] He refers to a 2017 study by Paul Baragli and his colleagues, in which horses subjected to the mirror test displayed clear signs of distinguishing between the reflection and a real animal.

[107] In the Turkish epic of Er-Töshtük, a folktale from Kyrgyzstan, the horse Tchal-Kouyrouk warns his rider, Töshtük, with these words: "Your chest is broad, but your mind is narrow; you think of nothing.

[110] The Mahi tale (from central Benin) titled Destiny tells of an orphan abandoned by his brothers who spares three horses destroying his crops and gains their help to win the love of a princess.

[S 176] Through Germanic pagan beliefs, historian Marc-André Wagner explores a progressive demonization of the horse, aimed at Christian leaders ending the ritualistic reverence once afforded to the animal.

[115] Wagner cites the example of the 7th-century text Vita de Columba of Iona, in which the Irish saint's horse lays its head on his knees and begins to weep, apparently sensing its imminent death:[115] To this crude and irrational animal, in the manner he chose, the Creator revealed in a manifest way that his master was going to leave him.According to S. C. Gupta et al., Tibetans in the cold, arid region of Ladakh believe that the intelligence of their small local Zanskari horses enabled warriors to achieve superior performance in regional wars during the 18th century.

[S 178] Anthropology lecturer Gregory Delaplace (2015) notes that the Mongols regard horses as companions and recognize not only their intelligence (uhaan) but also their ability to perceive and feel the invisible—a quality independent of intellect.

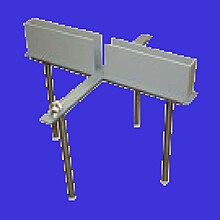

(A) A horse mounted at the midpoint between two plates containing droppings approaches the right plate and sniffs the target.

(B) About 5 minutes later, the horse is presented with a second choice and chooses the left target.

(C) About 5 minutes later, the horse is presented with a third choice and walks past the previous two targets without examining either. [ S 99 ]